|

5/26/2014 Are These Shoes Made for Running? Uncertainty, Complexity and Minimalist FootwearRead Now Repost from Technoscience as if People Mattered In almost every technoscientific controversy participants could take better account of the inescapable complexities of reality and the uncertainties of their knowledge. Unfortunately, many people suffer from significant cognitive barriers that prevent them from doing so. That is, they tend to carry the belief that their own side is in unique possession of Truth and that only their opponents are in any way biased, politically motivated or otherwise lacking in sufficient data to support their claims. This is just as clear in the case of Vibram Five Finger shoes (i.e., “toe shoes”) as it is for GMO’s and climate change. Much of humanity would be better off, however, if technological civilization responded to these contentious issues in ways more sensitive to uncertainty and complexity. Five Fingers are the quintessential minimalist shoe, receiving much derision concerning its appearance and skepticism about its purported health benefits. Advocates of the shoes claim that its minimalist design helps runners and walkers maintain a gait similar to being barefoot while enjoying protection from abrasion. Padded shoes, in contrast, seem to encourage heel striking and thereby stronger impact forces in runners’ knees and hips. The perceived desirability of a barefoot stride is in part based on the argument that it better mimics the biomechanical motion that evolved in humans over millennia and the observation of certain cultures that pursue marathon long-distance barefoot running. Correlational data suggests that people in places that more often eschew shoes suffer less from chronic knee problems, and some recent studies find that minimalist shoes do lead to improved foot musculature and decreased heel striking. Opponents, of course, are not merely aesthetically opposed to Five Fingers but mobilize their own sets of scientific facts and experts. Skeptics cite studies finding higher rates of injury among those transitioning to minimalist shoes than those wearing traditional footwear. Others point to “barefoot cultures” that still run with a heel striking gait. The recent settlement by Vibram with plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit, moreover, seems to have been taken as a victory of rational minds over pseudoscience by critics who compare the company to 19th century snake oil salesmen. Yet, this settlement was not an admission that the shoes did nothing but merely that recognition that there are not yet unequivocal scientific evidence to back up the company’s claims about the purported health benefits of the shoes.

Neither of the positions, pro or con, is immediately more “scientific” than the other. Both sides use value-laden heuristics to take a position on minimalist shoes in the absence of controlled, longitudinal studies that might settle the facts of the matter. The unspoken presumption among critics of minimalist shoes is that highly padded, non-minimalist shoes are unproblematic when really they are an unexamined sociotechnical inheritance. No scientific study has justified adding raised heels, pronation control and gel pads to sneakers. Advocates of minimalist shoes and barefoot running, on the other hand, trust the heuristic of “evolved biomechanics” and “natural gait” given the lack of substantial data on footwear. They put their trust in the argument that humans ran fine for millenia without heavily padded shoes. There is nothing inherently wrong, of course, about these value commitments. In everyday life as much as in politics, decisions must be made with incomplete information. Nevertheless, participants in debates over these decisions too frequently present themselves as in possession of a level of certainty they cannot possibly have, given that the science on what kinds of shoes humans ought to wear remains mostly undone. At the same time, it seems unfair to leave footwear consumers in the position of having to fumble with the decision between purchasing a minimalist or non-minimalist shoe. A technological civilization sensitized to uncertainty and complexity would take a different approach to minimalist shoes than the status quo process of market-led diffusion with very little oversight or monitoring. To begin, the burden of proof would be more appropriately distributed. Advocates of minimalist shoes are typically put in the position of having to prove the safety and desirability of them, despite the dearth of conclusive evidence whether or not contemporary running shoes are even safe. There are risks on both sides. Minimalist shoes may end up injuring those who embrace them or transition too quickly. However, if they do in fact encourage healthier biomechanics, it may be that multitudes of people have been and continue to be unnecessarily destined for knee and hip replacements by their clunky New Balances. Both minimalist and non-minimalist shoes need to be scrutinized. Second, use of minimalist shoes should be gradually scaled-up and matched with well-funded, multipartisan monitoring. Simply deploying an innovation with potential health benefits and detriments then waiting for a consumer response and, potentially, litigation means an unnecessarily long, inefficient and costly learning process. Longitudinal studies on Five Fingers and other minimalist shoes could have begun as soon as they were developed or, even better, when companies like Nike and Reebok started adding raised heels and gel pads. Monitoring of minimalist shoes, moreover, would need to be broad enough to take account of confounding variables introduced by cultural differences. Indeed, it is hard to compare American joggers to barefoot running Tarahumara Indians when the former have typically been wearing non-minimalist shoes for their whole lives and tend to be heavier and more sedentary. Squat toilets make for a useful analogy. Given the association of western toilets with hiatal hernias and other ills, abandoning them would seem like a good idea. However, not having grown up with them and likely being overweight or obese, many Westerners are unable to squat properly, if at all, and would risk injury using a squat toilet. Most importantly, multi-partisan monitoring would help protect against clear conflicts of interest. The controversy over minimalist and non-minimalist shoes impacts the interests of experts and businesses. There is a burgeoning orthotics and custom running shoes industry that not only earns quite a lot of revenue in selling special footwear and inserts but also certifies only certain people as having the “correct” expertise concerning walking and running issues. They are likely to adhere to their skepticism about minimalist shoes as strongly as oil executives do on climate change, for better or worse. Although large firms are quickly introducing their own minimalist shoes designs, a large-scale shift toward them would threaten their business models: Since minimalist shoes do not have cushioning that breaks down over time, there is no need to replace them every three to six months. Likewise, Vibram itself is unlikely to fully explore the potential limitations of their products. Finally, funds should have been set aside for potential victims. Given a long history of unintended consequences resulting from technological change, it should not have come as a surprise that a dramatic shift in footwear would produce injuries in some customers. Vibram Five Finger shoes, in this way, are little different from other innovations, such as the Toyota Prius’ electronically controlled accelerator pedal or novel medications like Vioxx. Had Vibram been forced to proactively set aside funds for potential victims, they would have been provided an incentive to more carefully study their shoes’ effects. Moreover, those ostensibly injured by the company’s product would not have to go through such a protracted and expensive legal battle to receive compensation. Although the process I have proposed might seem strange at first, the status quo itself hardly seems reasonable. Why should companies be permitted to introduce new products with little accountability for the risks posed to consumers and no requirements to discern what risks might exist? There is no obvious reason why footwear and sporting equipment should not be treated similarly to other areas of innovation where the issues of uncertainty and complexity loom large, like nanotechnology or new pharmaceuticals. The potential risks for acute and chronic harms are just as real, and the interests of manufacturers and citizens are just as much in conflict. Are Vibram Five Finger shoes made for running? Perhaps. But without changes to the way technological civilization governs new innovations, participants in any controversy are provided with neither the means nor sufficient incentive to find the answer. 5/15/2014 What Was Step Two Again? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress.Read Now Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Far too rarely do most people reflect critically on the relationship between advancing technoscience and progress. The connection seems obvious, if not “natural.” How else would progress occur except by “moving forward” with continuous innovation? Many, if not most, members of contemporary technological civilization seem to possess an almost unshakable faith in the power of innovation to produce an unequivocally better world. Part of the purpose of Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholarship is to precisely examine if, when, how and for whom improved science and technology means progress. Failing to ask these questions, one risks thinking about technoscience like how underpants gnomes think about underwear. Wait. Underpants gnomes? Let me back up for second. The underpants gnomes are characters from the second season of the television show South Park. They sneak into people’s bedrooms at night to steal underpants, even the ones that their unsuspecting victims are wearing. When asked why they collect underwear, the gnomes explain their “business plan” as follows: Step 1) Collect underpants, Step 2) “?”, Step 3) Profit! The joke hinges on the sheer absurdity of the gnomes’ single-minded pursuit of underpants in the face of their apparent lack of a clear idea of what profit means and how underpants will help them achieve it. Although this reference is by now a bit dated, these little hoarders of other people’s undergarments are actually one of the best pop-culture illustrations of the technocratic theory of progress that often undergirds people’s thinking about innovation. The historian of technology Leo Marx described the technocratic idea of progress as: "A belief in the sufficiency of scientific and technological innovation as the basis for general progress. It says that if we can ensure the advance of science-based technologies, the rest will take care of itself. (The “rest” refers to nothing less than a corresponding degree of improvement in the social, political, and cultural conditions of life.)" The technocratic understanding of progress amounts to the application of underpants gnome logic to technoscience: Step 1) Produce innovations, Step 2) “?”, Step 3) Progress! This conception of progress is characterized by a lack of a clear idea of not only what progress means but also how amassing new innovations will bring it about.

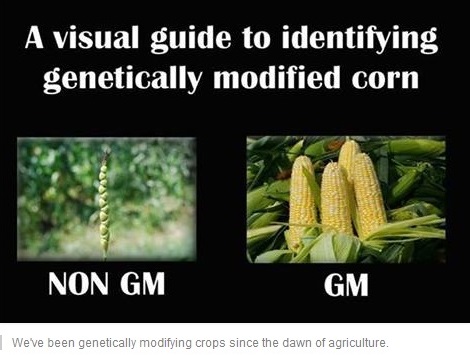

The point of undermining this notion of progress is not to say that improved technoscience does not or could not play an important role in bringing about progress but to recognize that there is generally no logical reason for believing it will automatically and autonomously do so. That is, “Step 2” matters a great deal. For instance, consider the 19th century belief that electrification would bring about a radical democratization of America through the emancipation of craftsmen, a claim that most people today will recognize as patently absurd. Given the growing evidence that American politics functions more like an oligarchy than a democracy, it would seem that wave after wave of supposedly “democratizing” technologies – from television to the Internet – have not been all that effective in fomenting that kind of progress. Moreover, while it is of course true that innovations like the polio vaccine, for example, certainly have meant social progress in the form of fewer people suffering from debilitating illnesses, one should not forget that such progress has been achievable only with the right political structures and decisions. The inventor of the vaccine, Jonas Salk, notably did not attempt to patent it, and the ongoing effort to eradicate polio has entailed dedicated global-level organization, collaboration and financial support. Hence, a non-technocratic civilization would not simply strive to multiply innovations under the belief that some vague good may eventually come out of it. Rather, its members would be concerned with whether or not specific forms of social, cultural or political progress will in fact result from any particular innovation. Ensuring that innovations lead to progress requires participants to think politically and social scientifically, not just technically. More importantly, it would demand that citizens consider placing limits on the production of technoscience that amounts to what Thoreau derided as “improved means to unimproved ends.” Proceeding more critically and less like the underpants gnomes means asking difficult and disquieting questions of technoscience. For example, pursuing driverless cars may lead to incremental gains in safety and potentially free people from the drudgery of driving, but what about the people automated out of a job? Does a driverless car mean progress to them? Furthermore, how sure should one be of the presumption that driverless cars (as opposed to less automobility in general) will bring about a more desirable world? Similarly, how should one balance the purported gains in yield promised by advocates of contemporary GMO crops against the prospects for a greater centralization of power within agriculture? How much does corn production need to increase to be worth the greater inequalities, much less the environmental risks? Moreover, does a new version of the iPhone every six months mean progress to anyone other than Apple’s shareholders and elite consumers? It is fine, of course, to be excited about new discoveries and inventions that overcome previously tenacious technical problems. However, it is necessary to take stock of where such innovations seem to lead. Do they really mean progress? More importantly, whose interests do they progress and how? Given the collective failure to demand answers to these sorts of questions, one has good reason to wonder whether technological civilization really is making progress. Contrary to the vision of humanity being carried up to the heavens of progress upon the growing peaks of Mt. Innovation, it might be that many of us are more like underpants gnomes dreaming of untold and enigmatic profits amongst piles of what are little better than used undergarments. One never knows unless one stops collecting long enough to ask, “What was step two again?” 5/5/2014 Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid: Continuity Arguments and Controversial TechnoScienceRead Now Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Far too much popular media and opinion is directed toward getting people to “Drink the Kool-Aid” and uncritically embrace controversial science and technology. One tool from Science and Technology Studies (STS) toolbox that can help prevent you from too quickly taking a swig is the ability to recognize and take apart continuity arguments. Such arguments take the form: Contemporary practice X shares some similarities with past practice Y. Because Y is considered harmless, it is implied that X must also be harmless. Consider the following meme about genetically modified organisms (GMO’s) from the "I Fucking Love Science" Facebook feed: This meme is used to argue that since selective breeding leads to the modification of genes, it is not significantly distinct from altering genetic code via any other method. The continuity of “modifying genetic code” from selective breeding to contemporary recombinant DNA techniques is taken to mean that the latter is no more problematic than the former. This is akin to arguing that exercise and proper diet is no different from liposuction and human-growth-hormone injections: They are all just techniques for decreasing fat and increasing muscle, right?

Continuity arguments, however, are usually misleading and mobilized for thinly veiled political reasons. As certain technology ethicists argue, “[they are] often an immunization strategy, with which people want to shield themselves from criticism and to prevent an extensive debate on the pros and cons of technological innovations.” Therefore, it is unsurprising to see continuity arguments abound within disagreements concerning controversial avenues of scientific research or technological innovation, such as GMO crops. Fortunately for you dear reader, they are not hard to recognize and tear apart. Here are the three main flaws in reasoning that characterize most continuity arguments. To begin, continuity arguments attempt to deflect attention away from the important technical differences that do exist. Selective breeding, for example, differs substantively from more recent genetic modification techniques. The former mimics already existing evolutionary processes: The breeder artificially creates an environmental niche for certain valued traits ensure survival by ensuring the survival and reproduction of only the organisms with those traits. Species, for the most part, can only be crossed if they are close enough genetically to produce viable offspring. One need not be an expert in genetic biology to recognize how the insertion of genetic material from very different species into another via retroviruses or other techniques introduces novel possibilities, and hence new uncertainties and risks, into the process. Second, the argument presumes that the past technoscientific practices being portrayed as continuous with novel ones are themselves unproblematic. Although selective breeding has been pretty much ubiquitous in human history, its application has not been without harm. For instance, those who oppose animal cruelty often take exception to the creation, maintenance and celebration of “pure” breeds. Not only does the cultural production of high status, expensive pedigrees provide a financial incentive for “puppy mills” but also discourages the adoption of mutts from shelters. Moreover, decades or centuries of inbreeding have produced animals that needlessly suffer from multiple genetic diseases and deformities, like boxers that suffer from epilepsy. Additionally, evidence is emerging that historical practices of selective breeding of food crops has rendered many of them much less nutritious. This, of course, is not news to “foodies” who have been eschewing iceberg lettuce and sweet onions for arugula and scallions for years. Regardless, one need not look far to see that even relatively uncontroversial technoscience has its problems. Finally and most importantly, continuity arguments assume away the environmental, social, and political consequences of large-scale sociotechnical change. At stake in the battle over GMO’s, for instance, are not only the potential unforeseen harms via ingestion but also the probable cascading effects throughout technological civilization. There are worries that the overliberal use of pesticides, partially spurred by the development of crops genetically modified to be tolerant of them, is leading to “superweeds” in the same way that the overuse of antibiotics lead to drug-resistant “superbugs.” GMO seeds, moreover, typically differ from traditional ones in that they are designed to “terminate” or die after a period of time. When that fails, Monsanto sues farmers who keep seeds from one season to the next. This ensures that Monsanto and other firms become the obligatory point of passage for doing agriculture, keeping farmers bound to them like sharecroppers to their landowner. On top of that, GMO’s, as currently deployed, are typically but one piece of a larger system of industrialized monoculture and factory farms. Therefore, the battle is not merely about the putative safety of GMO crops but over what kind of food and farm culture should exist: One based on centralized corporate power, lots of synthetic pesticides, and high levels of fossil fuel use along with low levels of biodiversity or the opposite? GMO continuity arguments deny the existence of such concerns. So the next time you hear or read someone claim that some new technological innovation or area of science is the same as something from the past: such as, Google Glasses not being substantially different from a smartphone or genetically engineering crops to be Roundup-ready not being significantly unlike selectively breeding for sweet corn, stop and think before you imbibe. They may be passing you a cup of Googleberry Blast or Monsanto Mountain Punch. Fortunately, you will be able to recognize the cyanide-laced continuity argument at the bottom and dump it out. Your existence as a critical thinking member of technological civilization will depend on it. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed