|

If there was a dominate media narrative during the pandemic, it was “ignorance is a virus.” It was a story reinforced by journalists, demonstrators, and public officials who simply could not comprehend the Americans who refused to get vaccinated. Misinformation became the second pandemic, the so-called “infodemic,” appearing to lead people to believe things like “COVID shots contain tracking devices.” Seemingly needed most was the reassertion of science’s authority. President Biden distinguished himself on the campaign trail by saying, “I believe in science. Donald Trump doesn’t,” promising to “marshal the forces of science” in his victory speech.

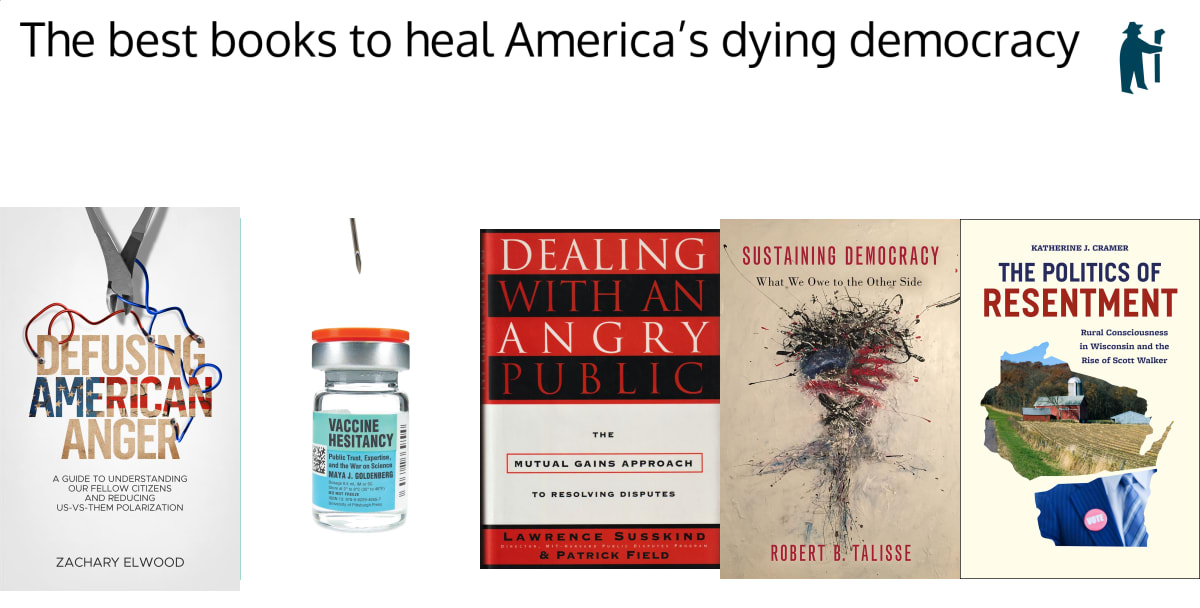

Yet, for all the pandemic-era lecturing to “follow the science” and mocking of citizens who failed to do so, American public health seems worse off today. Kindergarten vaccination rates have dropped from 95 to 93 percent since 2020, a level that makes measles outbreaks now possible among the 250 thousand unprotected five-year olds. That 28 percent of Americans are now opposed to mandatory school vaccinations portends further declines. While COVID may no longer loom large as an existential threat, Americans’ growing vaccine skepticism will continue to wreak havoc on public health efforts. The authority of science can no longer be taken for granted. It relies on political support and public trust. This is Robert Crease’s and Peter Bond’s argument in The Leak: Politics, Activists, and Loss of Trust at Brookhaven National Laboratory. A philosopher at Stonybrook and a Brookhaven Lab (BNL) physicist, respectively, Crease and Bond recount the aftermath of what should have been a trivial tritium leak at the Long Island, New York research facility. They tell of an innocent nuclear research reactor being shuttered because, in the words of a Physics Today columnist, “politics and protest prevailed.” Read the rest at Taming Complexity I wrote a short piece for the 4S blog, where I explore alternative roles for scientists and engineers in public controversies. More and more I believe that experts shouldn't be discerning what we "ought" to do about a situation (whether climate change or gas stoves). Nor are they used fully effectively as honest brokers. Rather, I think they should act as "thoughtful partisans", who use they expertise to facilitate more productive politics. Click here to read it.

If you tried to describe early 21st century politics with a single word, apocalyptic would be among the top contenders. From climate change and COVID to biodiversity change and abortion, the rhetoric surrounding most issues seems to be "The world (as you know it) is going to end. Only radical action can hope to save it." Whatever the merits of the argument that the relevant indicators have gone from merely "bad" to a "crisis" might be, the consequences from democracy have been deadly. Once political problems are framed as potentially apocalyptic, the implication that they are therefore too important or pressing to be solved by regular old democracy tends to be taken for granted. Participants become polarized and fanatical, seeing their opponents as not just behind the times or ignorant of "the facts" but enemies of the future of humanity. What's more is that it imposes a disaster narrative. And like a tornado bearing down upon us, the expectation is that people lay all other concerns to the side and just do what they're told. But as I've pointed out earlier, that story about the politics doesn't really hold up.

I think that we're not going to make consistent and dependable progress on the global crises we face until we can learn to talk about them as merely "big problems," rather than as cataclysm. Decades of political experience have told us that no amount of screaming about "the facts" or insisting on the stupidity or evilness of other people will make them drop their own political views and do what we tell them. Most of all, it only takes a bit of reflection to recognize that these problems are not at all like a disaster, like a tornado we can see with our own eyes. They depend upon our trust in experts and those communicating the science. The pandemic, for instance, is not something the average citizen perceives in its totality. It is a diffuse problem, one that people have to be constantly reminded of. Choosing to wear a mask or get vaccinated, as a result, is not at all like stacking sandbags in the face of rising flood waters. It is asking people to play their part in an improving epidemiological situation that is only understood to government modelers. It demands that people see imperceptibly influencing statistical projections of viral spread and healthcare burden as a heroic and necessary act. That can't be done except by building trust, by doing democracy, by convincing your opponents that you're not only credible but honest and benevolent. In any case, see more at The New Atlantis. Science and technology scholars write and talk a lot about post-normal science, the unique political situation that emerges for issues where there are considerable stakes and high levels of (perceived) uncertainty. I was asked to give a talk on short notice at the World Biodiversity Forum this week, and I used it as an opportunity to think through how people involved in areas of post-normal science and politics try to cope with or escape the situation of post-normality. Can the stakes be reduced while still addressing the problem? Can the perceived uncertainties be lessened without other stakeholders seeing it as dishonest, biased, or unfair? Those are just a few of the thoughts that I explored. Unfortunately, the talk wasn't recorded, but here is a link to the slides.

Biodiversity conservation is riddled with conflict. This is unsurprising, given that people live where we also find important and charismatic animal species. Although there has been a lot of good work looking into how to reconcile the often divergent interests of conservationists and rural peoples, I feel like a lot of it is on the wrong track. No doubt is it well intentioned. There is a long history of treating rural people as conservation "problems," one that goes at least as far back as efforts to remove native peoples from America's newly established national parks. The idea that species can only be protected by creating "pristine" wilderness areas is increasingly recognized as not only ahistorical but also the driving force behind the expropriation of land from rural residents. The future of conservation relies on moving past the historical antagonism between typically urban-dwelling, "science following" conservation advocates and the people who live within the landscapes seen as needing protection.

The response within conservation has paralleled a similar move within Science and Technology Studies, consequently suffering some of the same drawbacks. Researchers in STS have done great work to highlight the existence of "lay expertise," that non-scientists have important knowledge to contribute. Similarly, environmental scientists have uncovered how indigenous and local peoples often have an intricate understanding of their local environment and have developed strategies that allow them to live off the land in ways that sometimes more sustainable or supportive of biodiversity than what so-called modern people do. Work in both these areas try to encourage scientists to be more humble and open to listening to non-scientists. The risk is romanticizing lay people. Not all indigenous peoples have lived so sustainability. Mesoamerica, for instance, was once dominated by groups who sustained themselves as much by imperialism as by their home grown agricultural practices. More broadly the antithesis of "follow the science", can devolve into a kind of epistemological populism, where it is non-experts whose knowledge becomes sacrosanct or unquestionable. Recall how Newt Gingerich, in the lead up to the 2016 election, argued that American's belief that the country was more dangerous than in the past, despite statistics to the contrary, was all that mattered for the election. Democracy is served by putting different kinds of knowledge in conversation, not by venerating the little guy. The question here is not whether the average American is wrong or if FBI statistics are right, but why Americans would still feel unsafe despite this data. The apparent contradiction uncovers a unresolved problem that policy should address. I think that part of the problem is that we've confused political problems for knowledge conflicts. Past injustices were often justified by science, such as when pristine (read "human free") protected areas were argued to be the only way to preserve nature. So the appropriate response seems to be that we can prevent those injustices by elevating lay knowledge so as to be equal in value to science. The idea is that the power differential was created by the unequal weight given to different kinds of knowledge, but really the causality worked in the opposite direction: Power legitimates one group's knowledge over that of others. So we focus excessively on developing ways to give diverse forms of knowledge equal weight when the real issue is simply that the way we decide what is a problem and how to solve it is insufficiently democratic. We're treating the symptom rather than the cause. The way out is both agnostic and agonistic. I think it's better to not get into the morass of deciding which knowledge should have the most influence or whether different ways of knowing are or are not equal. Rather, groups with different ideas about what is important and different ways of knowing about the environment should have more equal say in deciding how to solve collective problems. We settle political conflicts through democracy, not convoluted analytical schemes for realizing epistemological equality. This is also the right way, because rural people should have a say in what conservation measures are deployed where they live and how, full stop. They have this right not because they have special knowledge or because they live in appropriately non-western or native ways, but because they live there and have a stake. No amount of scientific know-how justifies depriving someone else of a say in decisions that affect them, insofar as we want to live in democratic societies. In any case, if you intrigued by this line of thought, take a peak at a commentary that I recently published in One Earth. We have all heard stories of people pilloried online. One of the earliest instances occurred in South Korea in 2005, when a young woman’s dog pooped in a subway car and she didn’t clean it up. Someone had taken photographs with a flip phone and posted them online, unleashing nationwide public harassment. The most famous story from Twitter is that of communications director Justine Sacco, who in 2013, before a flight to South Africa, tweeted a hamfisted joke about getting AIDS. Even though she had only 170 Twitter followers, the post blew up — as did her life.

The two stories show rather different kinds and levels of offense and shaming. But they both illustrate the same reality. Once upon a time, an ill-advised comment or action drew an appropriately stern rebuke from a friend or a boss or a stranger; today it draws a public firestorm that can ruin you. So now everyone is on guard, because everyone is watching. Continued at The New Atlantis 1/19/2022 Fact-checking may be important, but it won’t help Americans learn to disagree betterRead Now Entering the new year, Americans are increasingly divided. They clash not only over differing opinions on COVID-19 risk or abortion, but basic facts like election counts and whether vaccines work. Surveying rising political antagonism, journalist George Packer recently wondered in The Atlantic, “Are we doomed?”... Continued at The Conversation

[We must] rethink the proper place of scientific expertise in policymaking and public deliberation. [An] inventory of the consequences of “follow the science” politics is sobering, applying to COVID-19 no less than to climate change and nuclear energy. When scientific advice is framed as unassailable and value-free, about-faces in policy undermine public trust in authorities. When “following the science” stifles debate, conflicts become a battle between competing experts and studies.

We must grapple with the complex and difficult trade-offs and judgment calls out in the open, rather than hide behind people in lab coats, if we are to successfully and democratically navigate the conflicts and crises that we face. Continued at ISSUES... Is it better to tolerate seemingly prejudiced political opinions, or should we be intolerant of people whose views on diversity, equity, and identity strike us as harmful?

I am an advocate for radically tolerating political disagreement, even if that disagreement strikes us as unmoored from facts or common sense. One reason is that dissent makes democracy more intelligent. While many believe that vaccine skeptics misunderstand the relevant science and threaten public health, their opposition to vaccines nevertheless draws attention to chronic problems within our medical system: financial conflicts of interest, racism and sexism, and other legitimate reasons for mistrust. People should have their voices heard because politics shapes the things citizens care about, not just the things they know. Tolerating disagreement also ensures the practice of democracy. Otherwise, we may find ourselves handing off ever more political control to experts and bureaucrats. Political truths can motivate fanaticism. Whether it is “follow the science” or “commonsense conservatism,” the belief that policy must actualize one’s own view of reality divides the world into “enlightened” good guys and ignorant enemies who just need to go away. But what about beliefs that seem harmful and intolerant? You might question, as the political philosopher Jonathan Marks does, whether a zealous belief in the idea “that all men are created equal” is so problematic. Why not divide the political world into citizens who believe in equality and harmfully ignorant people to be ignored? The trouble is that doing so makes actually achieving equality more difficult....Continued at Zocalo Public Square |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed