|

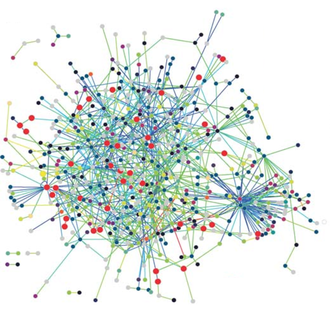

Back during the summer, Tristan Harris sparked a flurry of academic indignation when he suggested that we needed a new field called “Science & Technology Interaction” or STX, which would be dedicated to improving the alignment between technologies and social systems. Tweeters were quick to accuse him of “Columbizing,” claiming that such a field already existed in the form of Science & Technology Studies (STS) or similar such academic department. So ignorant, amirite?

I am far more sympathetic. If people like Harris (and earlier Cathy O’Neil) have been relatively unaware of fields like Science and Technology Studies, it is because much of the research within these disciplines is mostly illegible to non-academics, not all that useful to them, or both. I really don’t blame them for not knowing. I am even an STS scholar myself, and the table of contents of most issues of my field’s major journals don’t really inspire me to read further. And in fairness to Harris and contrary to Academic Twitter, the field of STX that he proposes does not already exist. The vast majority of STS articles and books dedicate single digit percentages of their words to actually imagining how technology could better match the aspirations of ordinary people and their communities. Next to no one details alternative technological designs or clear policy pathways toward a better future, at least not beyond a few pages at the end of a several-hundred-page manuscript. My target here is not just this particular critique of Harris, but the whole complex of academic opiners who cite Foucault and other social theory to make sure we know just how “problematic” non-academics’ “ignorant” efforts to improve technological society are. As essential as it is to try to improve upon the past in remaking our common world, most of these critiques don’t really provide any guidance for what steps we should be taking. And I think that if scholars are to be truly helpful to the rest of humanity they need to do more than tally and characterize problems in ever more nuanced ways. They need to offer more than the academic equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. In the case of Harris, we are told that underlying the more circumspect digital behavior that his organization advocates is a dangerous preoccupation with intentionality. The idea of being more intentional is tainted by the unsavory history of humanistic thought itself, which has been used for exclusionary purposes in the past. Left unsaid is exactly how exclusionary or even harmful it remains in the present. This kind of genealogical take down has become cliché. Consider how one Gizmodo blogger criticizes environmentalists’ use the word “natural” in their political activism. The reader is instructed that because early Europeans used the concept of nature to prop up racist ideas about Native Americans that the term is now inherently problematic and baseless. The reader is supposed to believe from this genealogical problematization that all human interactions with nature are equally natural or artificial, regardless of whether we choose to scale back industrial development or to erect giant machines to control the climate. Another common problematiziation is of the form “not everyone is privileged enough to…”, and it is often a fair objection. For instance, people differ in their individual ability to disconnect from seductive digital devices, whether due to work constraints or the affordability or ease of alternatives. But differences in circumstances similarly challenge people’s capacity to affordably see a therapist, retrofit their home to be more energy efficient, or bike to work (and one might add to that: read and understand Foucault). Yet most of these actions still accomplish some good in the world. Why is disconnection any more problematic than any other set of tactics that individuals use to imperfectly realize their values in an unequal and relatively undemocratic society? Should we just hold our breaths for the “total overhaul…full teardown and rebuild” of political economies that the far more astute critics demand? Equally trite are references to the “panopticon,” a metaphor that Foucault developed to describe how people’s awareness of being constantly surveilled leads them to police themselves. Being potentially visible at all times enables social control in insidious ways. A classic example is the Benthamite prison, where a solitary guard at the center cannot actually view all the prisoners simultaneously, but the potential for him to be viewing a prisoner at any given time is expected to reduce deviant behavior. This gets applied to nearly any area of life where people are visible to others, which means it is used to problematize nearly everything. Jill Grant uses it to take down the New Urbanist movement, which aspires (though fairly unsuccessfully) to build more walkable neighborhoods that are supportive of increased local community life. This movement is “problematic” because the densities it demands means that citizens are everywhere visible to their neighbors, opening up possibilities for the exercise of social control. Whether not any other way of housing human beings would not result in some form of residential panopticon is not exactly clear, except perhaps by designing neighborhoods so as to prohibit social community writ large. Further left unsaid in these critiques is exactly what a more desirable alternative would be. Or at least that alternative is left implicit and vague. For example, the pro-disconnection digital wellness movement is in need of enhanced wokeness, to better come to terms with “the political and ideological assumptions” that they take for granted and the “privileged” values they are attempting to enact in the world. But what does that actually mean? There’s a certain democratic thrust to the criticism, one that I can get behind. People disagree about what is “the good life” and how to get there, and any democratic society would be supportive of a multitude of them. Yet the criticism that the digital wellness movement seems to center around one vision of “being human,” one emphasizing mindfulness and a capacity to exercise circumspect individual choosing, seems hollow without the critics themselves showing us what should take its place. Whatever the flaws with digital wellness, it is not as self-stultifying as the defeatist brand of digital hedonism implicitly left in the wake of academic critiques that offer no concrete alternatives. Perhaps it is unfair to expect a full-blown alternative; yet few of these critiques offer even an incremental step in the right direction. Even worse, this line of criticism can problematize nearly everything, losing its rhetorical power as it is over-applied. Even academia itself is disciplining. STS has its own dominant paradigms, and critique is mobilized in order to mold young scholars into academics who cite the right people, quote the correct theories, and support the preferred values. My success depends on me being at least “docile enough” in conforming myself to the norms of the profession. I also exercise self-discipline in my efforts to be a better spouse and a better parent. I strive to be more intentional when I’m frustrated or angry, because I too often let my emotions shape my interactions with loved ones in ways that do not align with my broader aspirations. More intentionality in my life has been generally a good thing, so long as my expectations are not so unrealistic as to provoke more anxiety than the benefits are worth. But in a critical mode where self-discipline and intentionality automatically equate to self-subjugation, how exactly are people to exercise agency in improving their own lives? In any case, advocating devices that enable users to exercise greater intentionality over their digital practices is not a bad thing per se. Citizens pursue self-help, meditate, and engage in other individualistic wellness activities because the lives they live are constrained. Their agency is partly circumscribed by their jobs, family responsibilities, and incomes, not to mention the more systemic biases of culture and capitalism. Why is it wrong for groups like Harris’ center to advocate efforts that largely work within those constraints? Yet even that reading of the digital wellness movement seems uncharitable. Certainly Harris’ analysis lacks the sophistication of a technology scholar’s, but he has made it obvious that he recognizes that dominant business models and asymmetrical relations of power underlay the problem. To reduce his efforts to mere individualistic self-discipline is borderline dishonest, though he no doubt emphasizes the parts of the problem he understands best. Of course it will likely take more radical changes to realize the humane technology than Harris advocates, but it is not totally clear whether individualized efforts necessarily detract from people’s ability or the willingness demand more from tech firms and governments (i.e., are they like bottled water and other “inverted quarantines”?). At least that is a claim that should be demonstrated rather than presumed from the outset. At its worst, critical “problematizing” presents itself as its own kind of view from nowhere. For instance, because the idea of nature has been constructed in various biased throughout history, we are supposed to accept the view that all human activities are equally natural. And we are supposed to view that perspective as if it were itself an objective fact rather than yet another politically biased social construction. Various observers mobilize much the same critique about claims regarding the “realness” of digital interactions. Because presenting the category of “real life” as being apart from digital interactions is beset with Foulcauldian problematics, we are told that the proper response is to no longer attempt the qualitative distinctions that that category can help people make—whatever its limitations. It is probably no surprise that the same writer wanting to do away with the digital-real distinction is enthusiastic in their belief that the desires and pleasures of smartphones somehow inherently contain the “possibility…of disrupting the status quo.” Such critical takes give the impression that all technology scholarship can offer is a disempowering form of relativism, one that only thinly veils the author’s underlying political commitments. The critic’s partisanship is also frequently snuck in the backdoor by couching criticism in an abstract commitment to social justice. The fact that the digital wellness movement is dominated by tech bros and other affluent whites implies that it must be harmful to everyone else—a claim made by alluding to some unspecified amalgamation of oppressed persons (women, people of color, or non-cis citizens) who are insufficiently represented. It is assumed but not really demonstrated that people within the latter demographics would be unreceptive or even damaged by Harris’ approach. But given the lack of actual concrete harms laid out in these critiques, it is not clear whether the critics are actually advocating for those groups or that the social-theoretical existence of harms to them is just a convenient trope to make a mainly academic argument seem as if it actually mattered. People’s prospects for living well in the digital age would be improved if technology scholars more often eschewed the deconstructive critique from nowhere. I think they should act instead as “thoughtful partisans.” By that I mean that they would acknowledge that their work is guided by a specific set of interests and values, ones that are in the benefit of particular groups. It is not an impartial application of social theory to suggest that “realness” and “naturalness” are empty categories that should be dispensed with. And a more open and honest admission of partisanship would at least force writers to be upfront with readers regarding what the benefits would actually be to dispensing with those categories and who exactly would enjoy them—besides digital enthusiasts and ecomodernists. If academics were expected to use their analysis to the clear benefit of nameable and actually existing groups of citizens, scholars might do fewer trite Foucauldian analyses and more often do the far more difficult task of concretely outlining how a more desirable world might be possible. “The life of the critic easy,” notes Anton Ego in the Pixar film Ratatouille. Actually having skin in the game and putting oneself and one’s proposals out in the world where they can be scrutinized is far more challenging. Academics should be pushed to clearly articulate exactly how it is the novel concepts, arguments, observations, and claims they spend so much time developing actually benefit human beings who don’t have access to Elsevier or who don't receive seasonal catalogs from Oxford University Press. Without them doing so, I cannot imagine academia having much of a role in helping ordinary people live better in the digital age.

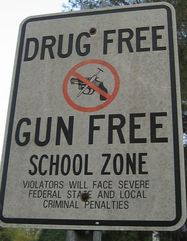

There have been no shortage of (mainly conservative) pundits and politicians suggesting that the path to fewer school shootings is armed teachers—and even custodians. Although it is entirely likely that such recommendations are not really serious but rather meant to distract from calls for stricter gun control legislation, it is still important to evaluate them. As someone who researches and teaches about the causes of unintended consequences, accidents, and disasters for a living, I find the idea that arming public school workers will make children safer highly suspect—but not for the reasons one might think.

If there is one commonality across myriad cases of political and technological mistakes, it would be the failure to acknowledge complexity. Nuclear reactors designed for military submarines were scaled up over an order of magnitude to power civilian power plants without sufficient recognition of how that affected their safety. Large reactors can get so hot that containing a meltdown becomes impossible, forcing managers to be ever vigilant to the smallest errors and install backup cooling systems—which only increased difficult to manage complexities. Designers of autopilot systems neglected to consider how automation hurt the abilities of airline pilots, leading to crashes when the technology malfunctioned and now-deskilled pilots were forced to take over. A narrow focus on applying simple technical solutions to complex problems generally leads to people being caught unawares by ensuing unanticipated outcomes. Debate about whether to put more guns in schools tends to emphasize the solution’s supposed efficacy. Given that even the “good guy with a gun” best positioned to stop the Parkland shooting failed to act, can we reasonably expect teachers to do much better? In light of the fact that mass shootings have even occurred at military bases, what reason do we have to believe that filling educational institutions with armed personnel will reduce the lethality of such incidents? As important as these questions are, they divert our attention to the new kinds of errors produced by applying a simplistic solution—more guns—to a complex problem. A comparison with the history of nuclear armaments should give us pause. Although most American during the Cold War worried about potential atomic war with the Soviets, Cubans, or Chinese, much of the real risks associated with nuclear weapons involve accidental detonation. While many believed during the Cuban Missile Crisis that total annihilation would come from nationalistic posturing and brinkmanship, it was actually ordinary incompetence that brought us closest. Strategic Air Command’s insistence on maintaining U2 and B52 flights and intercontinental ballistic missiles tests during periods of heightened risked a military response from the Soviet Union: pilots invariably got lost and approached Soviet airspace and missile tests could have been misinterpreted to be malicious. Malfunctioning computer chips made NORAD’s screens light up with incoming Soviet missiles, leading the US to prep and launch nuclear-armed jets. Nuclear weapons stored at NATO sites in Turkey and elsewhere were sometimes guarded by a single American soldier. Nuclear armed B52s crashed or accidently released their payloads, with some coming dangerously close to detonation. Much the same would be true for the arming of school workers: The presence and likelihood routine human error would put children at risk. Millions of potentially armed teachers and custodians translates into an equal number of opportunities for a troubled student to steal weapons that would otherwise be difficult to acquire. Some employees are likely to be as incompetent as Michelle Ferguson-Montogomery, a teacher who shot herself in the leg at her Utah school—though may not be so lucky as to not hit a child. False alarms will result not simply in lockdowns but armed adults roaming the halls and, as result, the possibility of children killed for holding cellphones or other objects that can be confused for weapons. Even “good guys” with guns miss the target at least some of the time. The most tragic unintended consequence, however, would be how arming employees would alter school life and the personalities of students. Generations of Americans mentally suffered under Cold War fears of nuclear war. Given the unfortunate ways that many from those generations now think in their old age: being prone to hyper-partisanship, hawkish in foreign affairs, and excessively fearful of immigrants, one worries how a generation of kids brought up in quasi-militarized schools could be rendered incapable of thinking sensibly about public issues—especially when it comes to national security and crime. This last consequence is probably the most important one. Even though more attention ought to be paid toward the accidental loss of life likely to be caused by arming school employees, it is far too easy to endlessly quibble about the magnitude and likelihood of those risks. That debate is easily scientized and thus dominated by a panoply of experts, each claiming to provide an “objective” assessment regarding whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks. The pathway out of the morass lies in focusing on values, on how arming teachers—and even “lockdown” drills— fundamentally disrupts the qualities of childhood that we hold dear. The transformation of schools into places defined by a constant fear of senseless violence turns them into places that cannot feel as warm, inviting, and communal as they otherwise could. We should be skeptical of any policy that promises greater security only at the cost of the more intangible features of life that make it worth living.

Although it seems clears that mid-20th century predictions of the demise of community have yet to come to pass—most people continue to socially connect with others—many observers are too quick to declare that all is well. Indeed, in my recent book, I critique the tendency by some contemporary sociologists to write as if people today have never had it better when it comes to social togetherness, as if we have reached a state of communal perfection. The way that citizens do community in contemporary technological societies has been breathlessly described as a new “revolutionary social operating system” that recreates the front porch of previous generations within our digital devices. There is quite a lot to say regarding how such pronouncements fail to give recognition to the qualitative changes to social life in the digital age, changes that impact how meaningful and satisfying people find it to be. Here I will just focus on one particular way in which contemporary community life is relatively thinner than what has existed at other times and places.

After she was raped in 2013, Gina Tron’s social networks were anything but revolutionary. In addition to the trauma of the act itself, she suffered numerous indignities in the process of trying to work within the contemporary justice system to bring charges against her attacker. During such trying times, at a moment when one would most need the loving support of friends, her social network abandoned her. Friends shunned her because they were afraid of having to deal with emotional outbursts, because they worried that just hearing about the experience would be traumatic, or because they felt that they would not be able to moan melodramatically about their more mundane complaints in the presence of someone with a genuine problem. Within the logic of networked individualism, that revolutionary social operating system extoled by some contemporary sociologists, such behavior is unsurprising. Social networks are defined not so much by commitment but by mutually advantageous social exchanges. Social atoms connect to individually trade something of value rather than because they share a common world or devotion to a common future. For members of Tron’s social network, the costs of connecting after her rape seemed to exceed the benefits; socializing in the aftermath of the event would force them to give more support than they themselves would receive. Even the institutions that had previously centered community life—namely churches—now often function similarly to weak social networks. Many evangelical churches seem more like weekly sporting events than neighborhood centers, boasting membership rolls in the thousands and putting on elaborate multimedia spectacles in gargantuan halls that often rival contemporary pop music acts. No doubt social networks do form through such places, providing smaller scale forms of togetherness and personal support in times of need. Yet there are often firm limits to the degree of support such churches will give, limits that many people would find horrifying. A large number of evangelical megachurches have their roots in and continue to preach prosperity theology. In this theological system, God is believed to reliably provide security and prosperity to those who are faithful and pious. A byproduct of such a view is that leaders of many, if not most, megachurches find it relatively unproblematic to personally enrich themselves with the offerings given by (often relatively impoverished) attendees, purchasing million dollar homes and expensive automobiles. Prosperity theology gives megachurch pastors a language through which they can frame such actions as anything but unethical or theologically contradictory, but rather merely a reflection and reinforcement of their own godliness. The worst outcome of prosperity theology comes out of logically deducing its converse: If piety brings prosperity, then hardship must be the result of sin and faithlessness. Indeed, as Kate Bowler describes, one megachurch asked a long-attending member stricken with cancer to stop coming to service. The fact that his cancer persisted, despite his membership, was taken as sign of some harmful impropriety; his presence, as a result, was viewed as posing a transcendental risk to the rest of the membership. It appears that, within prosperity theology, community is to be withdrawn from members in their moments of greatest need. However, many contemporary citizens have largely abandoned traditional religious institutions, preferring instead to worship at the altar of physical performance. CrossFit is especially noteworthy for both the zeal of its adherents and the viciousness of the charges launched by critics, who frequently describe the fitness movement as “cultlike.” Although such claims can seem somewhat exaggerated, there is some kernel of truth to them. Julie Beck, for instance, has recently noted the extreme evangelical enthusiasm of many CrossFitters. While there is nothing problematic about developing social community via physical recreation per se—indeed, athletic clubs and bowling leagues served that purpose in the past—what caught my eye about CrossFit was how easy it was to be pushed out of the community. There is an element of exclusivity to it. Adherents like to point to disabled members as evidence that CrossFit is ostensibly for everyone. Yet for those who get injured, partly as a result of the fitness movement’s narrow emphasis on “beat the clock” weightlifting routines at the expense of careful attention to form, frequently find themselves being assigned sole responsibility for damaging their bodies. Although the environment encourages—even deifies—the pushing of limits, individual members are themselves blamed if they go too far. In any case, those suffering an injury are essentially exiled, at least temporarily; there are no “social” memberships to CrossFit: You are either there pushing limits or not there at all. In contrast to Britney Summit-Gil’s argument that community is characterized by the ease by which people can leave, I contend that thick communities are defined by the stickiness of membership. I do not mean that it is necessarily hard to leave them—they are by no means cults—but that membership is not so easily revoked, and especially not during times of need. No doubt there are advantages to thinly communal social networks. People use them to advance their career, fundraise for important causes, and build open source software. Yet we should be wary of their underlying logic of limited commitment, of limited liability, becoming the model for community writ large. If social networks are indeed revolutionary, then we should carefully examine their politics: Do they really provide us with the “liberation” we seek or just new forms of hardship? Have new masters simply taken the place of the old ones? Those are questions citizens cannot begin to intelligently consider if they are too absorbed with marveling over new technical wonders, too busy standing in awe of the strength of weak ties.

Although Elon Musk's recent cryptic tweets about getting approval to build a Hyperloop system connecting New York and Washington DC are likely to be well received among techno-enthusiasts--many of whom see him as Tony Stark incarnate--there are plenty of reasons to remain skeptical. Musk, of course, has never shied away from proposing and implementing what would otherwise seem to be fairly outlandish technical projects; however, the success of large-scale technological projects depends on more than just getting the engineering right. Given that Musk has provided few signs that he considers the sociopolitical side of his technological undertakings with the same care that he gives the technical aspects (just look at the naivete of his plans for governing a Mars colony), his Hyperloop project is most likely going to be a boondoggle--unless he is very, very lucky.

Don't misunderstand my intentions, dear reader. I wish Mr. Musk all the best. If climate scientists are correct, technological societies ought to be doing everything they can to get citizens out of their cars, out of airplanes, and into trains. Generally I am in favor of any project that gets us one step closer to that goal. However, expensive failures would hurt the legitimacy of alternative transportation projects, in addition to sucking up capital that could be used on projects that are more likely to succeed. So what leads me to believe that the Hyperloop, as currently envisioned, is probably destined for trouble? Musk's proposals, as well as the arguments of many of his cheerleaders, are marked by an extreme degree of faith in the power of engineering calculation. This faith flies in the face of much of the history of technological change, which has primarily been a incremental, trial-and-error affair often resulting in more failures than success stories. The complexity of reality and of contemporary technologies dwarfs people's ability to model and predict. Hyman Rickover, the officer in charge of developing the Navy's first nuclear submarine, described at the length the significant differences between "paper reactors" and "real reactors," namely that the latter are usually behind schedule, hugely expensive, and surprisingly complicated by what would normally be trivial issues. In fact, part of the reason the early nuclear energy industry was such a failure, in terms of safety oversights and being hugely over budget, was that decisions were dominated by enthusiasts and that they scaled the technology up too rapidly, building plants six times larger than those that currently existed before having gained sufficient expertise with the technology. Musk has yet to build a full-scale Hyperloop, leaving unanswered questions as to whether or not he can satisfactorily deal with the complications inherent in shooting people down a pressurized tube at 800 miles an hour. All publicly available information suggests he has only constructed a one-mile mock-up on his company's property. Although this is one step beyond a "paper" Hyperloop, a NY to DC line would be approximately 250 times longer. Given that unexpected phenomena emerge with increasing scale, Musk would be prudent to start smaller. Doing so would be to learn from the US's and Germany's failed efforts to develop wind power in 1980s. They tried to build the most technically advanced turbines possible, drawing on recent aeronautical innovations. Yet their efforts resulted in gargantuan turbines that failed often within tens of operating hours. The Danes, in contrast, started with conventional designs, incrementally scaling up designs andlearning from experience. Apart from the scaling-up problem, Musk's project relies on simultaneously making unprecedented advances in tunneling technology. The "Boring Company" website touts their vision for managing to accomplish a ten-fold decrease in cost through potential technical improvements: increasing boring machine power, shrinking tunnel diameters, and (more dubiously) automating the tunneling process. As a student of technological failure, I would question the wisdom of throwing complex and largely experimental boring technology into a project that is already a large, complicated endeavor that Musk and his employees have too little experience with. A prudent approach would entail spending considerable time testing these new machines on smaller projects with far less financial risk before jumping headfirst into a Hyperloop project. Indeed, the failure of the US space shuttle can be partly attributed to the desire to innovate in too many areas at the same time. Moreover, Musk's proposals seem woefully uninformed about the complications that arise in tunnel construction, many of which can sink a project. No matter how sophisticated or well engineered the technology involved, the success of large-scale sociotechnical projects are incredibly sensitive to unanticipated errors. This is because such projects are highly capital intensive and inflexibly designed. As a result, mistakes increase costs and, in turn, production pressures--which then contributes to future errors. The project to build a 2 mile tunnel to replace the Alaska Way Viaduct, for instance, incurred a two year, quarter billion dollar delay after the boring machine was damaged after striking a pipe casing that went unnoticed in the survey process. Unless taxpayers are forced to pony up for those costs, you can be sure that tunnel tolls will be higher than predicted. It is difficult to imagine how many hiccups could stymie construction on a 250 mile Hyperloop. Such errors will invariably raise the capital costs of the project, costs that would need to be recouped through operating revenues. Given the competition from other trains, driving, and flying, too high of fares could turn the Hyperloop into a luxury transport system for the elite. Concorde anyone? Again, while I applaud Musk's ambition, I worry that he is not proceeding intelligently enough. Intelligently developing something like a Hyperloop system would entail focusing more on his own and his organization's ignorance, avoiding the tendency to become overly enamored with one's own technical acumen. Doing so would also entail not committing oneself too early to a certain technical outcome but designing so as to maximize opportunities for learning as well as ensuring that mistakes are relatively inexpensive to correct. Such an approach, unfortunately, is rarely compatible with grand visions of immediate technical progress, at least in the short-term. Unfortunately, many of us, especially Silicon Valley venture capitalists, are too in love with those grand visions to make the right demands of technologists like Musk.

The stock phrase that “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it” certainly seems to hold true for technological innovation. After a team of Stanford University researchers recently developed an algorithm that they say is better at diagnosing heart arrhythmias than a human expert, all the MIT Technology Review could muster was to rhetorically ask if patients and doctors could ever put their trust in an algorithm. I won’t dispute the potential for machine learning algorithms to improve diagnoses; however, I think we should all take issue when journalists like Will Knight depict these technologies so uncritically, as if their claimed merits will be unproblematically realized without negative consequences.

Indeed, the same gee-whiz reporting likely happened during the advent of computerized autopilot in the 1970s—probably with the same lame rhetorical question: “Will passengers ever trust a computer to land a plane?” Of course, we now know that the implementation of autopilot was anything but a simple story of improved safety and performance. As both Robert Pool and Nicholas Carr have demonstrated, the automation of facets of piloting created new forms of accidents produced by unanticipated problems with sensors and electronics as well as the eventual deskilling of human pilots. That shallow, ignorant reporting for similar automation technologies, including not just automated diagnosis but also technologies like driverless cars, continues despite the knowledge of those previous mistakes is truly disheartening. The fact that the tendency to not dig too deeply into the potential undesirable consequences of automation technologies is so widespread is telling. It suggests that something must be acting as a barrier to people’s ability to think clearly about such technologies. The political scientists Charles Lindblom called these barriers “impairments to critical probing,” noting the role of schools and the media in helping to ensure that most citizens refrain from critically examining the status quo. Such impairments to critical probing with respect to automation technologies are visible in the myriad simplistic narratives that are often presumed rather than demonstrated, such as in the belief that algorithms are inherently safer than human operators. Indeed, one comment on Will Knight’s article prophesized that “in the far future human doctors will be viewed as dangerous compared to AI.” Not only are such predictions impossible to justify—at this point they cannot be anything more than wildly speculative conjectures—but they fundamentally misunderstand what technology is. Too often people act as if technologies were autonomous forces in the world, not only in the sense that people act as if technological changes were foreordained and unstoppable but also in how they fail to see that no technology functions without the involvement of human hands. Indeed, technologies are better thought of as sociotechnical systems. Even a simple tool like a hammer cannot existing without underlying human organizations, which provide the conditions for its production, nor can it act in the world without it having been designed to be compatible with the shape and capacities of the human body. A hammer that is too big to be effectively wielded by a person would be correctly recognized as an ill-conceived technology; few would fault a manual laborer forced to use such a hammer for any undesirable outcomes of its use. Yet somehow most people fail to extend the same recognition to more complex undertakings like flying a plane or managing a nuclear reactor: in such cases, the fault is regularly attributed to “human error.” How could it be fair to blame a pilot, who only becomes deskilled as a result of their job requiring him or her to almost exclusively rely on autopilot, for mistakenly pulling up on the controls and stalling the plane during an unexpected autopilot error? The tendency to do so is a result of not recognizing autopilot technology as a sociotechnical system. Autopilot technology that leads to deskilled pilots, and hence accidents, is as poorly designed as a hammer incompatibly large for the human body: it fails to respect the complexities of the human-technology interface. Many people, including many of my students, find that chain of reasoning difficult to accept, even though they struggle to locate any fault with it. They struggle under the weight of the impairing narrative that leads them to assume that the substitution of human action with computerized algorithms is always unalloyed progress. My students’ discomfort is only further provoked when presented with evidence that early automated textile technologies produced substandard, shoddy products—most likely being implemented in order to undermine organized labor rather than to contribute to a broader, more humanistic notion of progress. In any case, the continued power of automation=progress narrative will likely stifle the development of intelligent debate about automated diagnosis technologies. If technological societies currently poised to begin automating medical care are to avoid repeating history, they will need to learn from past mistakes. In particular, how could AI be implemented so as to enhance the diagnostic ability of doctors rather than deskill them? Such an approach would part ways with traditional ideas about how computers should influence the work process, aiming to empower and “informate” skilled workers rather than replace them. As Siddhartha Mukherjee has noted, while algorithms can be very good at partitioning, e.g., distinguishing minute differences between pieces of information, they cannot deduce “why,” they cannot build a case for a diagnosis by themselves, and they cannot be curious. We only replace humans with algorithms at the cost of these qualities. Citizens of technological societies should demand that AI diagnostic systems are used to aid the ongoing learning of doctors, helping them to solidify hunches and not overlook possible alternative diagnoses or pieces of evidence. Meeting such demands, however, may require that still other impairing narratives be challenged, particularly the belief that societies must acquiescence to the “disruptions” of new innovations, as they are imagined and desired by Silicon Valley elites—or the tendency to think of the qualities of the work process last, if at all, in all the excitement over extending the reach of robotics. Few issues stoke as much controversy, or provoke as shallow of analysis, as net neutrality. Richard Bennett’s recent piece in the MIT Technology Review is no exception. His views represent a swelling ideological tide among certain technologists that threatens not only any possibility for democratically controlling technological change but any prospect for intelligently and preemptively managing technological risks. The only thing he gets right is that “the web is not neutral” and never has been. Yet current “net neutrality” advocates avoid seriously engaging with that proposition. What explains the self-stultifying allegiance to the notion that the Internet could ever be neutral?

Bennett claims that net neutrality has no clear definition (it does), that anything good about the current Internet has nothing to do with a regulatory history of commitment to net neutrality (something he can’t prove), and that the whole debate only exists because “law professors, public interest advocates, journalists, bloggers, and the general public [know too little] about how the Internet works.” To anyone familiar with the history of technological mistakes, the underlying presumption that we’d be better off if we just let the technical experts make the “right” decision for us—as if their technical expertise allowed them to see the world without any political bias—should be a familiar, albeit frustrating, refrain. In it one hears the echoes of early nuclear energy advocates, whose hubris led them to predict that humanity wouldn’t suffer a meltdown in hundreds of years, whose ideological commitment to an atomic vision of progress led them to pursue harebrained ideas like nuclear jets and using nuclear weapons to dig canals. One hears the echoes of those who managed America’s nuclear arsenal and tried to shake off public oversight, bringing us to the brink of nuclear oblivion on more than one occasion. Only armed with such a poor knowledge of technological history could someone make the argument that “the genuine problems the Internet faces today…cannot be resolved by open Internet regulation. Internet engineers need the freedom to tinker.” Bennett’s argument is really just an ideological opposition to regulation per se, a view based on the premise that innovation better benefits humanity if it is done without the “permission” of those potentially negatively affected. Even though Bennett presents himself as simply a technologist whose knowledge of the cold, hard facts of the Internet leads him to his conclusions, he is really just parroting the latest discursive instantiation of technological libertarianism. As I’ve recently argued, the idea of “permissionless innovation” is built on a (intentional?) misunderstanding of the research on how to intelligently manage technological risks as well as the problematic assumption that innovations, no matter how disruptive, have always worked out for the best for everyone. Unsurprisingly the people most often championing the view are usually affluent white guys who love their gadgets. It is easy to have such a rosy view of the history of technological change when one is, and has consistently been, on the winning side. It is a view that is only sustainable as long as one never bothers to inquire into whether technological change has been an unmitigated wonder for the poor white and Hispanic farmhands who now die at relatively younger ages of otherwise rare cancers, the Africans who have mined and continue to mine Uranium or coltan in despicable conditions, or the permanent underclass created by continuous technological upheavals in the workplace not paired with adequate social programs. In any case, I agree with Bennett’s argument in a later comment to the article: “the web is not neutral, has never been neutral, and wouldn't be any good if it were neutral.” Although advocates for net neutrality are obviously demanding a very specific kind of neutrality: that ISPs do not treat packets differently based on where they originate or where they’re going, the idea of net neutrality has taken on a much broader symbolic meaning, one that I think constrains people’s thinking about Internet freedoms rather than enhances it. The idea of neutrality carries so much rhetorical weight in Western societies because their cultures are steeped in a tradition of philosophical liberalism. Liberalism is a philosophical tradition based in the belief that the freedom of individuals to choose is the greatest good. Even American political conservatives really just embrace a particular flavor of philosophical liberalism, one that privileges the freedoms enjoyed by supposedly individualized actors unencumbered by social conventions or government interference to make market decisions. Politics in nations like the US proceeds with the assumption that society, or at least parts of it, can be composed in such a way to allow individuals to decide wholly for themselves. Hence, it is unsurprising that changes in Internet regulations provoke so much ire: The Internet appears to offer that neutral space, both in terms of the forms of individual self-expression valued by left-liberals and the purportedly disruptive market environment that gives Steve Jobs wannabes wet dreams. Neutrality is, however, impossible. As I argue in my recent book, even an idealized liberal society would have to put constraints on choice: People would have to be prevented from making their relationship or communal commitments too strong. As loathe as some leftists would be to hear it, a society that maximizes citizens’ abilities for individual self-expression would have to be even more extreme than even Margaret Thatcher imagined it: composed of atomized individuals. Even the maintenance of family structures would have to be limited in an idealized liberal world. On a practical level it is easy to see the cultivation of a liberal personhood in children as imposed rather than freely chosen, with one Toronto family going so far as to not assign their child a gender. On plus side for freedom, the child now has a new choice they didn’t have before. On the negative side, they didn’t get to choose whether or not they’d be forced to make that choice. All freedoms come with obligations, and often some people get to enjoy the freedoms while others must shoulder the obligations. So it is with the Internet as well. Currently ISPs are obliged to treat packets equally so that content providers like Google and Netflix can enjoy enormous freedoms in connecting with customers. That is clearly not a neutral arrangement, even though it is one that many people (including Google) prefer. However, the more important non-neutrality of the Internet, one that I think should take center stage in debates, is that it is dominated by corporate interests. Content providers are no more accountable to the public than large Internet service providers. At least since it was privatized in the mid-90s, the Internet has been biased toward fulfilling the needs of business. Other aspirations like improving democracy or cultivating communities, if the Internet has even really delivered all that much in those regards, have been incidental. Facebook wants you to connect with childhood friends so it can show you an ad for a 90s nostalgia t-shirt design. Google wants to make sure neo-nazis can find the Stormfront website so they can advertise the right survival gear to them. I don’t want a neutral net. I want one biased toward supporting well-functioning democracies and vibrant local communities. It might be possible for an Internet to do so while providing the wide latitude for innovative tinkering that Bennett wants, but I doubt it. Indeed, ditching the pretense of neutrality would enable the broader recognition of the partisan divisions about what the Internet should do, the acknowledgement that the Internet is and will always be a political technology. Whose interests do you want it to serve? Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered

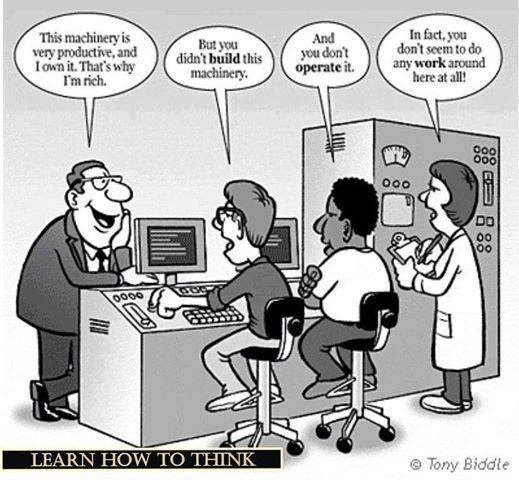

Opponents of regulatory changes that could mean the end of “net neutrality” or proposed legislation like the SOPA/PIPA acts of 2012 regularly contend that these policies would “break the Internet” in some significant way. They prophesize that such measures will lead to an Internet rotten to the core by political censorship or one less generative of creativity. Those on the other side, in response, turn out their own expert analysis meant to assure citizens that the intangible goods purportedly offered by the Internet – such as greater democracy or “innovation” writ large – are not really being undermined at all. In the continuous back and forth between these opposing sides, rarely is the question of whether or not “breaking” the contemporary Internet is actually undesirable given much thought or analysis. It is presumed rather than demonstrated that the current Web “works.” What reasons might we have to consider letting ISPs and content creators lead public policy toward a “broken” Net? Is the contemporary Internet really all that worth saving? To begin, there are grounds for wondering if the Internet has really been that much of a boon to democracy. Certainly critics like Hindman andMorozov – who point out how infrequently political concerns occupy web surfers, how most content production is dominated by a few elites, and that the Internet has had an ambivalent role in promoting enhanced democracy in totalitarian regimes – would likely warn against overestimating the actual democratic utility of contemporary digital networks. Arab Spring notwithstanding, the Internet seems to play as big a role in entertainment, “clicktivism” and commerce driven pacification of populations as their liberation. Though undoubtedly useful for activists needing a tool for organizing popular action across space and time, the Web is also a major vehicle for the “bread and circuses” (i.e., Amazon purchases and Netflix marathons) that too frequently aid citizen passivity. Moreover, as Jodi Dean points out, those championing the ostensible democratic properties of digital networks frequently overstate the political gains afforded by certain means for public communicative self-expression becoming “democratized.” Just because the Average Joe (or Jane) can now publish their own blog does not necessary mean that they have any more influence on public policy than before. Second, the image of the Internet as a bottom-up, decentralized and people-powered technology of liberation, for all intents and purposes, seems to be more myth than reality. From the physical infrastructure and the standardization of protocols to the provision of content through websites like Google and Facebook, the Internet is highly centralized and very often already steered by the interests of large corporations. Media scholars Robert McChesney and John Nichols, for instance, contend that the Internet has been one of the greatest drivers of economic monopoly in history. Likewise the depiction of the movement against measures that threaten net neutrality as strictly the bottom-up voice of the people is similarly a figment of collective imagination. That this opposition has any political traction has more to do with the fact that content providers like Netflix and others having a major financial stake in a non-tiered Internet than the bubbling over of popular democratic ferment. Purveyors of bandwidth hungry services profit greatly from a neutral net at the expense of ISPs, who, in turn, are looking for a bigger piece of the pie for themselves. Third, as Ethan Zuckerman has recently pointed out in an article for the Atlantic, the entrenched status-quo business model of the Internet is advertising. Getting an edge over the competition in advertising requires more effectively surveilling users. We have unintelligently steered ourselves to a Net that financially depends on users’ surfing and social activities being constantly tracked, monitored and analyzed. Users’ provision of “free cultural labor” to companies like Google and Facebook drives the contemporary Internet. The fact that the current Web depends so intimately on advertising, moreover, fuels “clickbait” journalism (think Upworthy), malware and high levels of economic centralization. Facebook’s acquiring of Instagram, as Zuckerman reminds us, was motivated by the company’s desire to maintain its demographic reach of advertising data points and targets. Size, and thereby access to big data, generally wins the day in an ad-driven Internet. Finally, for those of us who wish contemporary technological civilization offered more frequent opportunities for realizing vibrant face-to-face community, the Internet is more often “good enough” than a godsend. A Facebook homefeed or Netflix marathon provides a minimally satisfying substitute for the social connection and storytelling that occurred within local pubs, cafés and other civic institutions, spaces that centered community life at other times and places. Consider one stay-at-home mom’s recent blogging about the loneliness of contemporary motherhood, loneliness that she describes as persisting despite the much hyped connection offered by Facebook and other social networks. She recounts driving to Target just to feel the presence of other people, seeing fellow mothers but ultimately lacking the nerve to say what she feels: “Are you lonely too?… Can we be friends? Am I freaking you out? I don’t care. HOLD ME.” Digitally mediated contact and networked social “meetups” are means to social intimacy that many of us accept reluctantly. They are, at best, anodynes for the pain caused by all the barriers standing in the way of embodied communality: suburbia, gasoline prices, six-dollar pints of beer, and the fact that too many of us long ago became habituated to being homebodies and public-space introverts. The fact that the contemporary Web has these strikes against it, of course, does not necessarily mean that is better to break it than reform it. That claim hinges on the degree to which these facets of the Internet are entrenched and likely to strongly resist change. Are thin democracy, weak community and corporate dominance already obdurate features of the Net? Has the technology gained so much sociotechnical momentum that it seems unreasonable to expect anything better out of it? If the answer to these questions is “Yes,” then citizens have good reason for believing that the most desirable avenue for “moving forward” is the abandonment of the contemporary Internet. I am not first to suggest this course of action. A former champion of the Internet, Douglas Rushkoff , now advocates its abandonment in order to focus on building alternatives through mesh-network technologies. Mesh-networks are potentially advantageous in that surveillance is more difficult, they are structurally decentralized and appear to offer better opportunities for collective control and governance. Experimental community mesh networks are already up and running in Spain, Germany and Greece. If properly steered, they could be an integral part of the development of more substantively democratic and communitarian Internets. If that is truly the case, then resources currently being dedicated to fighting for net neutrality might be put to better use supporting experimentation with and the building of mesh-network alternatives to the current Internet. Letting ISPs have their way in the net neutrality debate, therefore, could prove to be a good thing. Users frustrated by increasing fees and choppy Netflix feeds are going to be more likely to be interested in Web alternatives than those with near perfect service. For the case of the Internet and improved democracy/community, perhaps letting things get worse is the only way they will ever get any better. 8/4/2014 Why Are Scientists and Engineers Content to Work for Scraps when MBAs get a Seat at the Table?Read Now Report from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Why should it be that some of the most brilliant and highly educated people I know are forced to beg for jobs and justify their work to managers who, in all likelihood, might have spent a greater part of their business program drunk than studying? Sure there are probably some useful tasks that managers and supervisors perform, and some of them are no doubt perfectly wonderful people. Nevertheless, why should they sit at the top of the hierarchy of the contemporary firm while highly skilled technologists just do what they are told? Why should those who design and build new technologies or solve tenacious scientific problems receive a wage and not a large share in the wealth they help generate? Most importantly, why do so many highly skilled and otherwise intelligent people put up with this situation? There is nothing natural about MBAs and other professional managers running a firm like a captain of ship. As Harvard economist Stephen Marglin illustrated so well, the emergence of that hierarchical system had little to do with improvements in technological efficiency or competitive superiority but rather that it better served the interests of capitalist owners. What bosses “do” is maximize the benefits accruing to capitalists at the expense of workers. Bosses have historically and continue to do this by minimizing the scope each individual worker has in the firm and inserting themselves (i.e., management) as the obligatory intermediary for even the most elementary of procedures. This allows them to better surveil and discipline workers for the benefit of owners. Most highly skilled workers will probably recognize this if they reflect on all those seemingly pointless memos they are forced to read and write. Of course, some separation of labor (and writing of memos) is necessary for achieving efficient production processes, but the current power arrangement ensures that exactly how any process ends up being partitioned is ultimately decided by and for the benefit of managers and owners prior to any consideration of workers’ interests.

Even if one were not bothered by the life-sucking monotony of many jobs inflicted by a strict separation of labor, there is still little reason why the person in charge of coordinating everyone’s individual tasks ought to rule with almost unquestioned authority. This is a particularly odd arrangement for tech firms, given that scientists and engineers are highly skilled workers whose creative talents make up the core the company’s success. Moreover, these workers only receive a wage while others (e.g., venture capitalists, shareholders and select managers) get the lion’s share of the generated wealth: “Thanks for writing the code for that app that made us millions. Here, have a bonus and count yourself lucky to have a job.” Although frequently taken to be “just the way things are,” it need not be the case that the totality of the profits of innovation so disproportionately accrue to shareholders and select managers. Neither does one need look as far away as socialist nations in order to recognize this. Family-owned and “closely held” corporations in the United States already forgo lower rates of monetary profit in order to enjoy non-monetary benefits and yet remain competitive. For instance, Hobby Lobby, recently made infamous for other reasons, closes its stores on Sundays. They give up sales to competitors like Michaels because those running the firm believe that workers ought to have a guaranteed day in their schedule to spend time with friends and loved ones. Companies like Chick-Fil-A, Wegman’s and others pay their workers more livable wages and/or help fund their college educations, all practices unlikely to maximize shareholder value by any stretch of the imagination. At the same time, the hiring process for many managers does not lend much credence to the view that their skills alone make the difference between a successful or unsuccessful company. Michael Church, for instance, recently posted an account of the differences between applying to tech firm as a software engineer versus a manager. When interviewing as a software engineer, the applicant was subjected to a barrage of doubts about their skills and qualifications. The burden of proof was laid on the applicant to prove themselves worthy. In contrast, when applying for a management position, the same applicant was seen as “already part of the club” and was targeted with hardly any scrutiny at all. This is, of course, but one example. I encourage readers to share their own experiences in the comments section. Regardless, I suspect that if management is regularly treated like a club for those with the right status rather than the right competencies, their skills may not be so scarce or essential as to justify their higher wages, stake in company assets and discretion in decision-making. Young, highly skilled workers seem totally unaware of the power they could have in their working lives, if enough of them strove to seize it. I am not talking about unionization, though that could also be helpful. Instead, I am suggesting that scientists and engineers could own and manage their own firms, reversing (or simply leveling) the hierarchy with their current business-major overlords. Doing so would not be socialism but rather economic democracy: a worker cooperative. Workers outside the narrow echelon of managers and distant venture capitalists could have stake in the ownership of capital and thus power in the firm, making it much more likely that their interests are better reflected in decisions about operations and longer-term business plans. There is no immediately obvious reason why scientists and engineers could not start their own worker cooperatives. In fact, there are cases of workers less skilled and educated than the average software engineer helping govern and earning equity in their companies. The Evergreen cooperative in Cleveland, Ohio, for instance, consists of a laundry – mostly serving a nearby hospital, a greenhouse and a weatherization contractor. A small percentage of each worker’s salary goes into owning a stake in the cooperative, amounting to about $65,000 in wealth in roughly eight years. Workers elect their own representation to the firm’s board and thus get a say in its future direction and daily operation. Engineers, scientists and other technologists are intelligent enough to realize that the current “normal” business hierarchy offers them a raw deal. If laundry workers and gardeners can cooperatively run a profitable business while earning wealth, not merely a wage, certainly those with the highly specialized, creative skills always being extolled as being the engine of the “new knowledge economy” could as well. The main barrier is psychological. Engineers, scientists and other technologists have been encultured to think that things work out best if they remain mere problem solvers – more cynical observers might say overhyped technicians. Maybe they believe they will be one of the lucky ones to work somewhere with free pizza, breakout rooms and a six figure salary, or maybe they think they will eventually break into management themselves. Of course there is also the matter of the start-up capital that any tech firm needs to get off the ground. Yet, if enough technologists started their own cooperative firms, they could eventually pool resources to finance the beginnings of other cooperative ventures. All it would take is a few dozen enterprising people to show their peers that they do not have to work for scraps (even if there are sometimes large paychecks to go with that free pizza). Rather, they could take a seat at the table. Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered

There has been no shortage of both hype and skepticism surrounding a proposed innovation whose creators champion as potentially solving North America’s energy woes: Solar Roadways. While there are reasonable concerns about the technical and economic viability of incorporating solar panels into street and highways, almost completely ignored are the sociopolitical facets of the issue. Even if they end up being technically and financially feasible, the question of “Why should we want them?” remains unanswered. Too readily do commentators forget that at stake is not merely how Americans get their electricity but the very organization of everyday life and the character of their communities. Solar Roadways technology is the brainchild of an Idaho start-up. It involves sandwiching photovoltaics between a textured, tempered road surface and a concrete bedding that houses other necessary electronics, such as storage batteries and/or the circuitry needed to connect it to the electrical grid. Others have raised issue over the fairly rosy estimates of these panels’ likely cost and potential performance, including their driveability and longevity as well as whether or not factors like snowfall, low temperatures in northern states and road grime will drastically reduce their efficiency. Given that life cycle analyses of rooftop solar panels estimate energy payback periods of ten to twenty years, any reduction in efficiency makes PV systems much less feasible. Will the panels actually last long enough to offset the energy it takes to build, distribute and install them? The extensive history of expensive technological failures should alert citizens to the need to address such worries before this technology is embraced on a massive scale. However, these reasonable technical concerns should not distract one from looking into the potential sociocultural consequences of implementing solar roadways. One of the main observations of Science and Technology Studies scholarship is that technologies have political consequences: Their very existence and functioning renders some choices and sets of actions possible and others more difficult if not impossible. One of the most obvious examples is how the transportation infrastructures implemented since the 1940’s have rendered walkable, vibrant urban areas in the United States exceedingly difficult to realize. Residents of downtown Albany, for instance, are practically prohibited from being able to choose to have a pleasant waterfront area on the edge of the Hudson River because mid-twentieth century state legislators decided to put I-787 there (partly in order to facilitate their own commutes into the city). Contemporary advocates for an accessible and vibrant waterfront not only face opposition from today’s legislators but also the disincentives posed by the costs and difficulties of moving millions of tons of sunk concrete and disrupting the established transportation network. Solar Roadways, therefore, is not merely a promising green energy idea but also potentially a mechanism for further entrenching the current transportation system of roads and highways. It is politically consequential technology. Most citizens are already committed to the highway and automobile system for their transportation needs, in part also due to the intentional dismantling and neglect of public transit. Having to rely on the highway and road system for electricity would only make moving away from car culture and toward walkable cities more difficult. It is socially and politically challenging to alter infrastructure once it is entrenched. Dismantling a solarfied I-787 in Albany, for example, would not simply require disrupting transportation networks but energy systems as well. If states were to implement solar roadways, it would be effectively an act of legislation that helps ensure that automobile-oriented lifestyles remain dominant for decades to come. This further entrenchment of automobility may be exactly why the idea of solar roadways seems so enticing to some. Solar Roadways is an example of what is known in Science and Technology Studies as a “techno-fix.” It promises the solving of complex sociotechnical problems through a “miracle” innovation and, hence, without the need to make difficult social and political decisions (see here for an STS-inspired take). That is, solar roadways are so alluring because they seem to provide an easy solution to the problems of climate change and growing energy scarcity. No need to implement carbon taxes, drive less or better regulate industry and the exploitation non-renewable resources, the technology will fix everything! To be fair, techno-fixes are not always bad. The point is only that one should be cautiously critical of them in order to not risk falling victim to wide-eyed techno-idealism. Some readers, of course, might still be skeptical of my interpretation of solar roadways as techno-fix perhaps aimed more at saving car culture than creating a more sustainable technological civilization. However, one simply need to ask “Why roadways rather than rooftops?” It does not take much expertise in renewable energy technologies to recognize that solar panels on rooftops make much more sense than on streets, highways and parking lots: They last longer because they are not subject to having cars and trucks drive on them; they can be angled to maximize the incidence of the sun’s rays; and there is likely just as much unused roof space as asphalt. Given all the additional barriers they face, it seems hard to deny that some of appeal of solar roadways is not technical but cultural: They promise the stabilization and entrenchment of a valued but likely unsustainable way of life. Nevertheless, I do not want to simply shoot down solar roadway technology but ask “How could it be used to support ways of life other than car culture?” Critically analyzing a technology from a Science and Technology Studies perspective can often lead to recommendations for its reconstruction, not simply its abandonment. I would suggest reinterpreting this proposed innovation as solar walkways rather than roadways, given that their longevity is more certain if subjected to footsteps instead of multi-ton vehicles. Moreover, as urban studies scholars have documented for decades, most urban and suburban spaces in North America suffer from a lack of quality public space. City plazas and town squares might seem more “rational” to municipal planners if their walking surfaces were made up of PV panels. Better yet, consider incorporating piezoelectrics at the same time and generate additional electricity from the pedestrians walking on it. Feed this energy into a collectively owned community energy system and one has the makings of a technology that, along with a number of other sociotechnical and political changes, could help make more vibrant, public urban spaces easier to realize. Citizens, certainly, could decide that solar walkways are no more feasible or attractive than solar roadways, and should investigate potential uses that go far beyond what I have suggested. Regardless, part of the point of Science and Technology Studies is to creatively re-imagine how technologies and social structures could mutually reinforce each other in order to support alternative or more desirable ways of life. Despite all the Silicon Valley rhetoric around “disruption,” new innovations tend be framed and implemented in ways that favor the status quo and, in turn, those who benefit from it. The supposed “disruption” posed by solar roadway technology is little different. Members of technological civilization would be better off if they not only asked of new innovations “Is it feasible?” but also “Does it support a sustainable and desirable way of life?” Solar freakin’ roadways might be viable, but citizens should reconsider if they really want the solar freakin’ car culture that comes with it. 5/26/2014 Are These Shoes Made for Running? Uncertainty, Complexity and Minimalist FootwearRead Now Repost from Technoscience as if People Mattered In almost every technoscientific controversy participants could take better account of the inescapable complexities of reality and the uncertainties of their knowledge. Unfortunately, many people suffer from significant cognitive barriers that prevent them from doing so. That is, they tend to carry the belief that their own side is in unique possession of Truth and that only their opponents are in any way biased, politically motivated or otherwise lacking in sufficient data to support their claims. This is just as clear in the case of Vibram Five Finger shoes (i.e., “toe shoes”) as it is for GMO’s and climate change. Much of humanity would be better off, however, if technological civilization responded to these contentious issues in ways more sensitive to uncertainty and complexity. Five Fingers are the quintessential minimalist shoe, receiving much derision concerning its appearance and skepticism about its purported health benefits. Advocates of the shoes claim that its minimalist design helps runners and walkers maintain a gait similar to being barefoot while enjoying protection from abrasion. Padded shoes, in contrast, seem to encourage heel striking and thereby stronger impact forces in runners’ knees and hips. The perceived desirability of a barefoot stride is in part based on the argument that it better mimics the biomechanical motion that evolved in humans over millennia and the observation of certain cultures that pursue marathon long-distance barefoot running. Correlational data suggests that people in places that more often eschew shoes suffer less from chronic knee problems, and some recent studies find that minimalist shoes do lead to improved foot musculature and decreased heel striking. Opponents, of course, are not merely aesthetically opposed to Five Fingers but mobilize their own sets of scientific facts and experts. Skeptics cite studies finding higher rates of injury among those transitioning to minimalist shoes than those wearing traditional footwear. Others point to “barefoot cultures” that still run with a heel striking gait. The recent settlement by Vibram with plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit, moreover, seems to have been taken as a victory of rational minds over pseudoscience by critics who compare the company to 19th century snake oil salesmen. Yet, this settlement was not an admission that the shoes did nothing but merely that recognition that there are not yet unequivocal scientific evidence to back up the company’s claims about the purported health benefits of the shoes.

Neither of the positions, pro or con, is immediately more “scientific” than the other. Both sides use value-laden heuristics to take a position on minimalist shoes in the absence of controlled, longitudinal studies that might settle the facts of the matter. The unspoken presumption among critics of minimalist shoes is that highly padded, non-minimalist shoes are unproblematic when really they are an unexamined sociotechnical inheritance. No scientific study has justified adding raised heels, pronation control and gel pads to sneakers. Advocates of minimalist shoes and barefoot running, on the other hand, trust the heuristic of “evolved biomechanics” and “natural gait” given the lack of substantial data on footwear. They put their trust in the argument that humans ran fine for millenia without heavily padded shoes. There is nothing inherently wrong, of course, about these value commitments. In everyday life as much as in politics, decisions must be made with incomplete information. Nevertheless, participants in debates over these decisions too frequently present themselves as in possession of a level of certainty they cannot possibly have, given that the science on what kinds of shoes humans ought to wear remains mostly undone. At the same time, it seems unfair to leave footwear consumers in the position of having to fumble with the decision between purchasing a minimalist or non-minimalist shoe. A technological civilization sensitized to uncertainty and complexity would take a different approach to minimalist shoes than the status quo process of market-led diffusion with very little oversight or monitoring. To begin, the burden of proof would be more appropriately distributed. Advocates of minimalist shoes are typically put in the position of having to prove the safety and desirability of them, despite the dearth of conclusive evidence whether or not contemporary running shoes are even safe. There are risks on both sides. Minimalist shoes may end up injuring those who embrace them or transition too quickly. However, if they do in fact encourage healthier biomechanics, it may be that multitudes of people have been and continue to be unnecessarily destined for knee and hip replacements by their clunky New Balances. Both minimalist and non-minimalist shoes need to be scrutinized. Second, use of minimalist shoes should be gradually scaled-up and matched with well-funded, multipartisan monitoring. Simply deploying an innovation with potential health benefits and detriments then waiting for a consumer response and, potentially, litigation means an unnecessarily long, inefficient and costly learning process. Longitudinal studies on Five Fingers and other minimalist shoes could have begun as soon as they were developed or, even better, when companies like Nike and Reebok started adding raised heels and gel pads. Monitoring of minimalist shoes, moreover, would need to be broad enough to take account of confounding variables introduced by cultural differences. Indeed, it is hard to compare American joggers to barefoot running Tarahumara Indians when the former have typically been wearing non-minimalist shoes for their whole lives and tend to be heavier and more sedentary. Squat toilets make for a useful analogy. Given the association of western toilets with hiatal hernias and other ills, abandoning them would seem like a good idea. However, not having grown up with them and likely being overweight or obese, many Westerners are unable to squat properly, if at all, and would risk injury using a squat toilet. Most importantly, multi-partisan monitoring would help protect against clear conflicts of interest. The controversy over minimalist and non-minimalist shoes impacts the interests of experts and businesses. There is a burgeoning orthotics and custom running shoes industry that not only earns quite a lot of revenue in selling special footwear and inserts but also certifies only certain people as having the “correct” expertise concerning walking and running issues. They are likely to adhere to their skepticism about minimalist shoes as strongly as oil executives do on climate change, for better or worse. Although large firms are quickly introducing their own minimalist shoes designs, a large-scale shift toward them would threaten their business models: Since minimalist shoes do not have cushioning that breaks down over time, there is no need to replace them every three to six months. Likewise, Vibram itself is unlikely to fully explore the potential limitations of their products. Finally, funds should have been set aside for potential victims. Given a long history of unintended consequences resulting from technological change, it should not have come as a surprise that a dramatic shift in footwear would produce injuries in some customers. Vibram Five Finger shoes, in this way, are little different from other innovations, such as the Toyota Prius’ electronically controlled accelerator pedal or novel medications like Vioxx. Had Vibram been forced to proactively set aside funds for potential victims, they would have been provided an incentive to more carefully study their shoes’ effects. Moreover, those ostensibly injured by the company’s product would not have to go through such a protracted and expensive legal battle to receive compensation. Although the process I have proposed might seem strange at first, the status quo itself hardly seems reasonable. Why should companies be permitted to introduce new products with little accountability for the risks posed to consumers and no requirements to discern what risks might exist? There is no obvious reason why footwear and sporting equipment should not be treated similarly to other areas of innovation where the issues of uncertainty and complexity loom large, like nanotechnology or new pharmaceuticals. The potential risks for acute and chronic harms are just as real, and the interests of manufacturers and citizens are just as much in conflict. Are Vibram Five Finger shoes made for running? Perhaps. But without changes to the way technological civilization governs new innovations, participants in any controversy are provided with neither the means nor sufficient incentive to find the answer. |

Details