|

[We must] rethink the proper place of scientific expertise in policymaking and public deliberation. [An] inventory of the consequences of “follow the science” politics is sobering, applying to COVID-19 no less than to climate change and nuclear energy. When scientific advice is framed as unassailable and value-free, about-faces in policy undermine public trust in authorities. When “following the science” stifles debate, conflicts become a battle between competing experts and studies.

We must grapple with the complex and difficult trade-offs and judgment calls out in the open, rather than hide behind people in lab coats, if we are to successfully and democratically navigate the conflicts and crises that we face. Continued at ISSUES... Is it better to tolerate seemingly prejudiced political opinions, or should we be intolerant of people whose views on diversity, equity, and identity strike us as harmful?

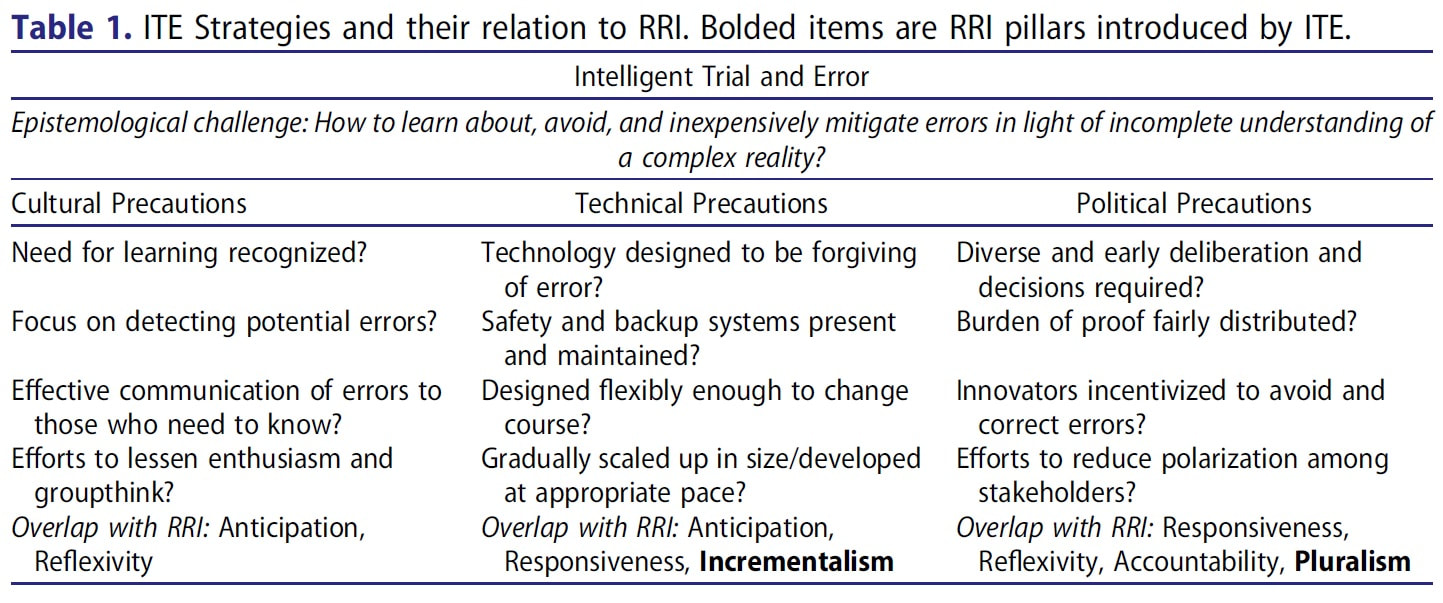

I am an advocate for radically tolerating political disagreement, even if that disagreement strikes us as unmoored from facts or common sense. One reason is that dissent makes democracy more intelligent. While many believe that vaccine skeptics misunderstand the relevant science and threaten public health, their opposition to vaccines nevertheless draws attention to chronic problems within our medical system: financial conflicts of interest, racism and sexism, and other legitimate reasons for mistrust. People should have their voices heard because politics shapes the things citizens care about, not just the things they know. Tolerating disagreement also ensures the practice of democracy. Otherwise, we may find ourselves handing off ever more political control to experts and bureaucrats. Political truths can motivate fanaticism. Whether it is “follow the science” or “commonsense conservatism,” the belief that policy must actualize one’s own view of reality divides the world into “enlightened” good guys and ignorant enemies who just need to go away. But what about beliefs that seem harmful and intolerant? You might question, as the political philosopher Jonathan Marks does, whether a zealous belief in the idea “that all men are created equal” is so problematic. Why not divide the political world into citizens who believe in equality and harmfully ignorant people to be ignored? The trouble is that doing so makes actually achieving equality more difficult....Continued at Zocalo Public Square This is a more academic piece of writing than I usually post, but I want to help make a theory so central to my thinking more accessible. This is an except from a paper that I had published in The Journal of Responsible Innovation a few years ago. If you find this intriguing, Intelligent Trial and Error (ITE) also showed up in an article that I wrote for The New Atlantis last year. The Intelligent Steering of Technoscience ITE is a framework for betting understanding and managing the risks of innovation, largely developed via detailed studies of cases of both technological error and instances when catastrophe had been fortuitously averted (see Morone and Woodhouse 1986; Collingridge 1992). Early ITE research focused on mistakes made in developing large-scale technologies like nuclear energy and the United States’ space shuttle program. More recently, scholars have extended the framework in order to explain partially man-made disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans (Woodhouse 2007), as well as more mundane and slow moving tragedies, like the seemingly inexorable momentum of sprawling suburban development (Dotson 2016). Although similar to high-reliability theory (Sagan 1993), an organizational model that tries to explain why accidents are so rare on aircraft carriers and among American air traffic controllers, ITE has a distinct lineage. The framework’s roots lie in political incrementalism (Lindblom 1959; Woodhouse and Collingridge 1993; Genus 2000). Incrementalism begins with a recognition of the limits of analytical rationality. Because analysts lack the necessary knowledge to predict the results of a policy change and are handicapped by biases, their own partisanship, and other cognitive shortcomings, incrementalism posits that they should—and very often do—proceed in a gradual and decentralized fashion. Policy therefore evolves via mutual adjustment between partisan groups, an evolutionary process that can be stymied when some groups’ desires—namely business’—dominate decision making. In short, pluralist democracy outperforms technocratic politics. Consider how elite decision makers in pre-Katrina New Orleans eschewed adequate precautions, having come to see flooding risks as acceptable or less important than supporting the construction industry; encouraging and enabling myriad constituent groups to advocate for their own interests in the matter would have provoked deliberations more likely to have led to preventative action (see Woodhouse 2007). In any case, later political scientists and decision theorists extended incrementalism to technological development (Collingridge 1980; Morone and Woodhouse 1986). ITE also differs from technology assessment, though both seek to avoid undesirable unintended consequences (see Genus 2000). Again, ITE is founded on a skepticism of analysis: the ramifications of complex technologies are highly unpredictable. Consequences often only become clear once a sociotechnical system has already become entrenched (Collingridge 1980). Hence, formal analytical risk assessments are insufficient. Lacking complete understanding, participants should not try to predict the future but instead strategize to lessen their ignorance. Of course, analysis still helps. Indeed, ITE research suggests that technologies and organizations with certain characteristics hinder the learning process necessary to minimize errors, characteristics that preliminary assessments can uncover. Expositions of ITE vary (cf. Woodhouse 2013; Collingridge 1992; Dotson 2017); nevertheless, all emphasize meeting the epistemological challenge of technological change: can learning happen quickly and without high costs? The failure to face up to this challenge not only leads to major mistakes for emerging technologies but can also stymie innovation in already established areas. The ills associated with suburban sprawl persists, for instance, because most learning happens far too late (Dotson 2016). Can developers be blamed for staying the course when innovation “errors” are learned about only after large swaths of houses have already been built? Regardless, meeting this central epistemological challenge requires employing three interrelated kinds of precautionary strategies. The first set of precautions are cultural. Are participants and organizations and prepared to learn? Is feedback produced early enough and development appropriately paced so that participants can feasibly change course? Does adequate monitoring by the appropriate experts occur? Is that feedback effectively communicated to those affected and those who decide? Such ITE strategies were applied by early biotechnologists at the Asilomar Conference: They put a moratorium on the riskiest genetic engineering experiments until more testing could be done, proceeding gradually as risks became better understood, and communicating the results broadly (Morone and Woodhouse 1986). In contrast, large-scale technological mistakes—from nuclear energy to irrigation dams in developing nations—tend to occur because they are developed and deployed by a group of true believers who fail to fathom that they could be wrong (Collingridge 1992).

Another set of strategies entail technical precautions. Even if participants are disposed to emphasize and respond to learning, does the technology’s design enable precaution? Sociotechnical systems can be made forgiving of unanticipated occurrences by ensuring wide margins for error, including built-in redundancies and backup systems, and giving preference to designs that are flexible or easily altered. The designers of the 20th century nuclear industry pursued the first two strategies but not the third. Their single-minded pursuit of economies of scale combined with the technology’s capital intensiveness all but locked-in the light water reactor design prior to a full appreciation of its inherent safety limitations (Morone and Woodhouse 1989). No doubt the technical facet of ITE intersects with its cultural dimensions: a prevailing bias toward a rapid pace of innovation can create technological inflexibility just as well as overly capital-intensive or imprudently scaled technical designs (cf. Collingridge 1992; Woodhouse 2016). Finally, there are political precautions. Do existing regulations, incentives, deliberative forums, and other political creations push participants toward more precautionary dispositions and technologies? Innovators may not be aware of the full range of risks or their own ignorance if deliberation is insufficiently diverse. AIDs sufferers, for instance, understood their own communities’ needs and health practices far better than medical researchers (Epstein 1996). Their exclusion slowed the development of appropriate treatment options and research. Moreover, technologies are less likely to be flexibly designed if deliberation on potential risks occurs too late in the innovation process. Finally, do regulations protect against widely shared conflicts of interest, encourage error correction, and enforce a fair distribution of the burden of proof? Regulatory approaches that demand “sound science” prior to regulation put the least empowered participants (i.e., victims) in the position of having to convincingly demonstrate their case and fail to incentivize innovators to avoid mistakes. In contrast, making innovators pay into victim’s funds until harm is disproven would encourage precaution by introducing a monetary incentive to prevent errors (Woodhouse 2013, 79). Indeed, mining companies already have to post remediation bonds to ensure that funds exist to clean up after valuable minerals and metals have been unearthed. To these political precautions, I would add the need for deliberative activities to build social capital (see Fleck 2016). Indeed, those studying commons tragedies and environmental management have outlined how establishing trust and a vision of some kind of common future—often through more informal modes of communication—are essential for well-functioning forms of collective governance (Ostrom 1990; Temby et al. 2017). Deliberations are unlikely to lead to precautionary action and productively working through value disagreements if proceedings are overly antagonistic or polarized. The ITE framework has a lot of similarities to Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) but differs in a number of important ways. RRI’s four pillars of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten 2013) are reflected in ITE’s focus on learning. Innovators must be pushed to anticipate that mistakes will happen, encouraged to reflect upon appropriate ameliorative action, and made to include and be accountable to potential victims. ITE can also be seen as sharing RRI’s connection to deliberative democratic traditions and the precautionary principle (see Reber 2018). ITE differs, however, in terms of scope and approach. Indeed, others have pointed out that the RRI framework could better account for the material barriers and costs and prevailing power structures that can prevent well-meaning innovators from innovating responsibly (De Hoop, Pols and Romijn 2016). ITE’s focus on ensuring technological flexibility, countering conflicts of interest, and fostering diversity in decision-making power and fairness in the burden of proof exactly addresses those limitations. Finally, ITE emphasizes political pluralism, in contrast to RRI’s foregrounding of ethical reflexivity. Innovators need not be ethically circumspect about their innovations provided that they are incentivized or otherwise encouraged by political opponents to act as if they were. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed