|

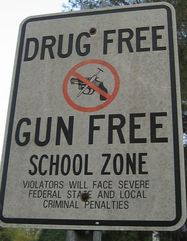

There have been no shortage of (mainly conservative) pundits and politicians suggesting that the path to fewer school shootings is armed teachers—and even custodians. Although it is entirely likely that such recommendations are not really serious but rather meant to distract from calls for stricter gun control legislation, it is still important to evaluate them. As someone who researches and teaches about the causes of unintended consequences, accidents, and disasters for a living, I find the idea that arming public school workers will make children safer highly suspect—but not for the reasons one might think.

If there is one commonality across myriad cases of political and technological mistakes, it would be the failure to acknowledge complexity. Nuclear reactors designed for military submarines were scaled up over an order of magnitude to power civilian power plants without sufficient recognition of how that affected their safety. Large reactors can get so hot that containing a meltdown becomes impossible, forcing managers to be ever vigilant to the smallest errors and install backup cooling systems—which only increased difficult to manage complexities. Designers of autopilot systems neglected to consider how automation hurt the abilities of airline pilots, leading to crashes when the technology malfunctioned and now-deskilled pilots were forced to take over. A narrow focus on applying simple technical solutions to complex problems generally leads to people being caught unawares by ensuing unanticipated outcomes. Debate about whether to put more guns in schools tends to emphasize the solution’s supposed efficacy. Given that even the “good guy with a gun” best positioned to stop the Parkland shooting failed to act, can we reasonably expect teachers to do much better? In light of the fact that mass shootings have even occurred at military bases, what reason do we have to believe that filling educational institutions with armed personnel will reduce the lethality of such incidents? As important as these questions are, they divert our attention to the new kinds of errors produced by applying a simplistic solution—more guns—to a complex problem. A comparison with the history of nuclear armaments should give us pause. Although most American during the Cold War worried about potential atomic war with the Soviets, Cubans, or Chinese, much of the real risks associated with nuclear weapons involve accidental detonation. While many believed during the Cuban Missile Crisis that total annihilation would come from nationalistic posturing and brinkmanship, it was actually ordinary incompetence that brought us closest. Strategic Air Command’s insistence on maintaining U2 and B52 flights and intercontinental ballistic missiles tests during periods of heightened risked a military response from the Soviet Union: pilots invariably got lost and approached Soviet airspace and missile tests could have been misinterpreted to be malicious. Malfunctioning computer chips made NORAD’s screens light up with incoming Soviet missiles, leading the US to prep and launch nuclear-armed jets. Nuclear weapons stored at NATO sites in Turkey and elsewhere were sometimes guarded by a single American soldier. Nuclear armed B52s crashed or accidently released their payloads, with some coming dangerously close to detonation. Much the same would be true for the arming of school workers: The presence and likelihood routine human error would put children at risk. Millions of potentially armed teachers and custodians translates into an equal number of opportunities for a troubled student to steal weapons that would otherwise be difficult to acquire. Some employees are likely to be as incompetent as Michelle Ferguson-Montogomery, a teacher who shot herself in the leg at her Utah school—though may not be so lucky as to not hit a child. False alarms will result not simply in lockdowns but armed adults roaming the halls and, as result, the possibility of children killed for holding cellphones or other objects that can be confused for weapons. Even “good guys” with guns miss the target at least some of the time. The most tragic unintended consequence, however, would be how arming employees would alter school life and the personalities of students. Generations of Americans mentally suffered under Cold War fears of nuclear war. Given the unfortunate ways that many from those generations now think in their old age: being prone to hyper-partisanship, hawkish in foreign affairs, and excessively fearful of immigrants, one worries how a generation of kids brought up in quasi-militarized schools could be rendered incapable of thinking sensibly about public issues—especially when it comes to national security and crime. This last consequence is probably the most important one. Even though more attention ought to be paid toward the accidental loss of life likely to be caused by arming school employees, it is far too easy to endlessly quibble about the magnitude and likelihood of those risks. That debate is easily scientized and thus dominated by a panoply of experts, each claiming to provide an “objective” assessment regarding whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks. The pathway out of the morass lies in focusing on values, on how arming teachers—and even “lockdown” drills— fundamentally disrupts the qualities of childhood that we hold dear. The transformation of schools into places defined by a constant fear of senseless violence turns them into places that cannot feel as warm, inviting, and communal as they otherwise could. We should be skeptical of any policy that promises greater security only at the cost of the more intangible features of life that make it worth living. Comments are closed.

|

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed