|

Are Americans losing their grip on reality? It is difficult not to think so in light of the spread of QANON conspiracy theories, which posit that a deep-state ring of Satanic pedophiles is plotting against President Trump. A recent poll found that some 56% of Republican voters believe that at least some of the QANON conspiracy theory is true. But conspiratorial thinking has been on the rise for some time. One 2017 Atlantic article claimed that America had “lost its mind” in its growing acceptance of post-truth. Robert Harris has more recently argued that the world had moved into an “age of irrationality.” Legitimate politics is threatened by a rising tide of unreasonableness, or so we are told. But the urge to divide people in rational and irrational is the real threat to democracy. And the antidote is more inclusion, more democracy—no matter how outrageous the things our fellow citizens seem willing to believe.

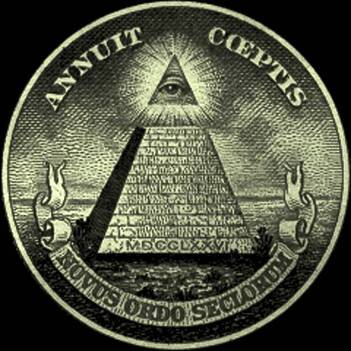

Despite recent panic over the apparent upswing in political conspiracy thinking, salacious rumor and outright falsehoods has been an ever-present feature of politics. Today’s lurid and largely evidence-free theories about left-wing child abuse rings have plenty of historical analogues. Consider tales of Catherine the Great’s equestrian dalliances and claims that Marie Antoinette found lovers in both court servants and within her own family. Absurd stories about political elites seems to have been anything but rare. Some of my older relatives believed in the 1990s that the government was storing weapons and spare body parts underneath Denver International Airport in preparation for a war against common American citizens—and that was well before the Internet was a thing. There seems to be little disagreement that conspiratorial thinking threatens democracy. Allusions to Richard Hofstadter’s classic essay on the “paranoid style of American politics” have become cliché. Hofstadter’s targets included 1950s conservatives that saw Communist treachery around every corner, 1890s populists railing against the growing power of the financial class, and widespread worries about the machinations of the Illuminati. He diagnosed their politics paranoid in light of their shared belief that the world was being persecuted by a vast cabal of morally corrupt elites. Regardless of their specific claims, conspiracy theories’ harms come from their role in “disorienting” the public, leading citizens to have grossly divergent understandings of reality. And widespread conspiratorial thinking drives the delegitimation of traditional democratic institutions like the press and the electoral system. Journalists are seen as pushing “fake news.” The voting booths become “rigged.” Such developments are no doubt concerning, but we should think carefully about how we react to conspiracism. Too often the response is to endlessly lament the apparent end of rational thought and wonder aloud if democracy can survive while being gripped by a form of collective madness. But focusing on citizens' perceived cognitive deficiencies presents its own risks. Historian Ted Steinberg called this the “diagnostic style” of American political discourse, which transforms “opposition to the cultural mainstream into a form of mental illness.” The diagnostic style leads us to view QANONers, and increasingly political opponents in general, as not merely wrong but cognitively broken. They become the anti-vaxxers of politics. While QANON believers certainly seem to be deluding themselves, isn’t the tendency by leftists to blame Trump’s popular support on conservative’s faculty brains and an uneducated or uninformed populace equally delusional? The extent to which such cognitive deficiencies are actually at play is beside the point as far as democracy is concerned. You can’t fix stupid, as the well-worn saying has it. Diagnosing chronic mental lapses actually leaves us very few options for resolving conflicts. Even worse, it prevents an honest effort to understand and respond to the motivations of people with strange beliefs. Calling people idiots will only cause them to dig in further. Responses to the anti-vaxxer movement show as much. Financial penalties and other compulsory measures tend to only anger vaccine hesitant parents, leading them to more often refuse voluntary vaccines and become more committed in their opposition. But it does not take a social scientific study to know this. Who has ever changed their mind in response to the charge of stupidity or ignorance? Dismissing people with conspiratorial views blinds us to something important. While the claims themselves might be far-fetched, people often have legitimate reasons for believing them. African Americans, for instance, disproportionately believe conspiracy theories regarding the origin of HIV, such as that it was man-made in a laboratory or that the cure was being withheld, and are more hesitant of vaccines. But they also rate higher in distrust of medical institutions, often pointing to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and ongoing racial disparities as evidence. And from British sheepfarmers’ suspicion of state nuclear regulators in the aftermath of Chernobyl to mask skeptics’ current jeremiads against the CDC, governmental mistrust has often developed after officials’ overconfident claims about the risks turned out to be inaccurate. What might appear to an “irrational” rejection of the facts is often a rational response to a power structure that feels distant, unresponsive, and untrustworthy. The influence of psychologists has harmed more than it has helped in this regard. Carefully designed studies purport to show that believers in conspiracy theories lack the ability to think analytically or claim that they suffer from obscure cognitive biases like “hypersensitive agency detection.” Recent opinion pieces exaggerate the “illusory truth effect,” a phenomenon discovered in psych labs that repeated exposure to false messages leads to a relatively slight increase in the number subjects rating them as true or plausible. The smallness of this, albeit statistically significant, effect doesn’t stop commentators from presenting social media users as if they were passive dupes, who only need to be told about QANON so many times before they start believing it. Self-appointed champions of rationality have spared no effort to avoid thinking about the deeper explanations for conspiratorial thinking. Banging the drum over losses in rationality will not get us out of our present situation. Underneath our seeming inability to find more productive political pastures is a profound misunderstanding of what makes democracy work. Hand Wringing over “post-truth” or conspiratorial beliefs is founded on the idea that the point of politics is to establish and legislate truths. Once that is your conception of politics, the trouble with democracy starts to look like citizens with dysfunctional brains. When our fellow Americans are recast as cognitively broken, it becomes all too easy to believe that it would be best to exclude or diminish the influence of people who believe outrageous things. Increased gatekeeping within the media or by party elites and scientific experts begins to look really attractive. Some, like philosopher Jason Brennan, go even further. His 2016 book, Against Democracy, contends that the ability to rule should be limited to those capable of discerning and “correctly” reasoning about the facts, while largely sidestepping the question of who decides what the right facts are and how to know when we are correctly reasoning about them. But it is misguided to think that making our democracy only more elitist will throttle the wildfire spread of conspiratorial thinking. If anything, doing so will only temporarily contain populist ferment, letting pressure build until it eventually explodes or (if we are lucky) economic growth leads it to fizzle out. Political gatekeeping, by mistaking supposed deficits in truth and rationality for the source of democratic discord, fails to address the underlying cause of our political dysfunction: the lack of trust. Signs of our political system’s declining legitimacy are not difficult to find. A staggering 71 percent of the Americans believe that elected officials don’t care about the average citizen or what they think. Trust in our government has never been lower, with only 17 percent of citizens expressing confidence about Washington most or all the time. By diagnosing rather than understanding, we cannot see that conspiratorial thinking is the symptom rather than the disease. The spread of bizarre theories about COVID-19 being a “planned” epidemic or child-abuse rings is a response to real feelings of helplessness, isolation, and mistrust as numerous natural and manmade disasters unfold before our eyes—epochal crises that governments seem increasingly incapable of getting a handle on. Many of Hofstadter’s listed examples of conspiratorial thought came during similar moments: at the height of the Red Scare and Cold War nuclear brinkmanship, during the 1890s depression, or in the midst of pre-Civil War political fracturing. Conspiracy theories offer a simplified world of bad guys and heroes. A battle between good and evil is a more satisfying answer than the banality of ineffectual government and flawed electoral systems when one is facing wicked problems. Perhaps social media adds fuel to the fire, accelerating the spread of outlandish proposals about what ails the nation. But it does so not because it short-circuits our neural pathways to crash our brains’ rational thinking modules. Conspiracy theories are passed by word of mouth (or Facebook likes) by people we already trust. It is no surprise that they gain traction in a world where satisfying solutions to our chronic, festering crises are hard to find, and where most citizens are neither afforded a legible glimpse into the workings of the vast political machinery that determines much of their lives nor the chance to actually substantially influence it. Will we be able to reverse course before it is too late? If mistrust and unresponsiveness is the cause, the cure should be the effort to reacquaint Americans with the exercise of democracy on a broad-scale. Hofstadter himself noted that, because the political process generally affords more extreme sects little influence, public decisions only seemed to confirm conspiracy theorists’ belief that they are a persecuted minority. The urge to completely exclude “irrational” movements forgets that finding ways to partially accommodate their demands is often the more effective strategy. Allowing for conscientious objections to vaccination effectively ended the anti-vax movement in early 20th century Britain. Just as interpersonal conflicts are more easily resolved by acknowledging and responding to people’s feelings, our seemingly intractable political divides will only become productive by allowing opponents to have some influence on policy. That is not to say that we should give into all their demands. Rather it is only that we need to find small but important ways for them to feel heard and responded to, with policies that do not place unreasonable burdens on the rest of us. While some might pooh-pooh this suggestion, pointing to conspiratorial thinking as evidence of how ill-suited Americans are for any degree of political influence, this gets the relationship backwards. Wisdom isn’t a prerequisite to practicing democracy, but an outcome of it. If our political opponents are to become more reasonable it will only be by being afforded more opportunities to sit down at the table with us to wrestle with just how complex our mutually shared problems are. They aren’t going anywhere, so we might as well learn how to coexist. As a scholar concerned about the value of democracy within contemporary societies, especially with respect to the challenges presented by increasingly complex (and hence risky) technoscience, a good check for my views is to read arguments by critics of democracy. I had hoped Jason Brennan's Against Democracy would force me to reconsider some of the assumptions that I had made about democracy's value and perhaps even modify my position. Hoped.

Having read through a few chapters, I am already disappointed and unsure if the rest of the book is worth the my time. Brennan's main assertion is that because some evidence shows that participation in democratic politics has a corrupting influence--that is, participants are not necessarily well informed and often end becoming more polarized and biased in the process--we would be better off limiting decision making power to those who have proven themselves sufficiently competent and rational, to epistocracy. Never mind the absurdity of the idea that a process for judging those qualities in potential voters could ever be made in an apolitical, unbiased, or just way, Brennan does not even begin with a charitable or nuanced understanding of what democracy is or could be. One early example that exposes the simplicity of Brennan's understanding of democracy--and perhaps even the circularity of his argument--is a thought experiment about child molestation. Brennan asks the reader to consider a society that has deeply deliberated the merits of adults raping children and subjected the decision to a majority vote, with the yeas winning. Brennan claims that because the decision was made in line with proper democratic procedures, advocates of a proceduralist view of democracy must see it as a just outcome. Due to the clear absurdity and injustice of this result, we must therefore reject the view that democratic procedures (e.g., voting, deliberation) themselves are inherently just. What makes this thought experiment so specious is that Brennan assumes that one relatively simplistic version of a proceduralist, deliberative democracy can represent the whole. Ever worse, his assumed model of deliberative democracy--ostensibly not too far from what already exists in most contemporary nations--is already questionably democratic. Not only is majoritarian decision-making and procedural democracy far from equivalent, but Brennan makes no mention of whether or not children themselves were participants in either the deliberative process or the vote, or even would have a representative say through some other mechanism. Hence, in this example Brennan actually ends up showing the deficits of a kind of epistocracy rather than democracy, insofar as the ostensibly more competent and rationally thinking adults are deliberating and voting for children. That is, political decisions about children already get made by epistocrats (i.e., adults) rather than democratically (understood as people having influence in deciding the rules by which they will be governed for the issues they have a stake in). Moreover, any defender of the value of democratic procedures would likely counter that a well functioning democracy would contain processes to amplify or protect the say of less empowered minority groups, whether through proportional representation or mechanisms to slow down policy or to force majority alliances to make concessions or compromises. It is entirely unsurprising that democratic procedures look bad when one's stand-in for democracy is winner-take-all, simple majoritarian decision-making. His attack on democratic deliberations is equally short-sighted. Criticizing, quite rightly, that many scholars defend deliberative democracy with purely theoretical arguments, while much of the empirical evidence shows that many average people dislike deliberation and are often very bad at it, Brennan concludes that, absent promising research on how to improve the situation, there is no logical reason to defend deliberative democracy. This is where Brennan's narrow disciplinary background as a political theorist biases his viewpoint. It is not at all surprising to a social scientist that average people would fail to deliberate well nor like it when the near entirety of contemporary societies fails to prepare them for democracy. Most adults have spent 18 years or more in schools and up to several decades in workplaces that do not function as democracies but rather are authoritarian, centrally planned institutions. Empirical research on deliberation has merely uncovered the obvious: People with little practice with deliberative interactions are bad at them. Imagine if an experiment put assembly line workers in charge of managing General Motors, then justified the current hierarchical makeup of corporate firms by pointing to the resulting non-ideal outcomes. I see no reason why Brennan's reasoning about deliberative democracy is any less absurd. Finally, Brennan's argument rests on a principle of competence--and concurrently the claim that citizens have a right to governments that meet that principle. He borrows the principle from medical ethics, namely that a patient is competent if they are aware of the relevant facts, can understand them, appreciate their relevance, and can reason about them appropriately. Brennan immediately avoids the obvious objections about how any of the judgements about relevance and appropriateness could be made in non-political ways to merely claim that the principle is non-objectionable in the abstract. Certainly for the simplified thought examples that he provides of plumber's unclogging pipes and doctors treating patients with routine conditions the validity of the principle of competence is clear. However, for the most contentious issues we face: climate change, gun control, genetically modified organisms, etc., the facts themselves and the reliability of experts are themselves in dispute. What political system would best resolve such a dispute? Obviously it could not be a epistocracy, given that the relevance and appropriateness of the "relevant" expertise itself is the issue to be decided. Perhaps Brennan's suggestions have some merit, but absent a non-superficial understanding of the relationship between science and politics the foundation of his positive case for epistocracy is shaky at best. His oft repeated assertion that epistocracy would likely produce more desirable decisions is highly speculative. I plan on continuing to examine Brennan's arguments regarding democracy, but I find it ironic that his argument against average citizens--that they suffer too much from various cognitive maladies to reason well about public issues--applies equally to Brennan. Indeed, the hubris of most experts is deeply rooted in their unfounded belief that a little learning has freed them from the mental limitations that infect the less educated. In reality, Brennan is a partisan like anyone else, not a sagely academic doling out objective advice. Whether one turns to epistocratic ideas in light of the limitations of contemporary democracies or advocate for ensuring the right preconditions for democracies to function better comes back to one's values and political commitments. So far it seems that Brennan's book demonstrates his own political biases as much as it exposes the ostensibly insurmountable problems for democracy. When reading some observer's diagnoses of what ails the United States, one can get the impression that Americans are living in an unprecedented age of public scientific ignorance. There is reason, however, to wonder if people today are really any more ignorant of facts like water boiling at lower temperatures at higher altitudes or if any more people believe in astrology than in the past. According to some studies, Americans have never been more scientifically literate. Nevertheless, there is no shortage of hand-wringing about the remaining degree of public scientific illiteracy and what it might mean for the future of the United States and American democracy. Indeed, scientific illiteracy is targeted as the cause of the anti-vaccination movement as well as opposition to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and nuclear power. However, I think such arguments misunderstand the issue. If America has a problem with regard to science, it is not due to a dearth of scientific literacy but a decline in science's public legitimacy.

The thinking underlying worries about widespread scientific illiteracy is rooted in what is called the “deficit model.” In the deficit model, the cause of the discrepancy between the beliefs of scientists and those are the public is, in the words of Dietram Scheufele and Matthew Nisbet, a “failure in transmission.” That is, it is believed that negligence of the media to dutifully report the “objective” facts or the inability of an irrational public to correctly receive those facts prevents the public from having the “right” beliefs regarding issues like science funding or the desirability of technologies like genetically modified organisms. Indeed, a blogger for Scientific American blames the opposition of liberals to nuclear power on “ignorance” and “bad psychological connections.” It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to say that the deficit model depicts anyone who is not a technological enthusiast as uninformed, if not idiotic. Regardless of whether or not the facts regarding these issues are actually “objective” or totally certain (both sides dispute the validity of each other’s arguments on scientific grounds), it remains odd that deficit model commentators view the discrepancy between scientists’ and the public’s views on GMOs and other issues as a problem for democracy. Certainly they are correct that it is preferable to have a populace that can think critically and suffers from few cognitive impairments to inquiry when it comes to wise public decision making. Yet, the idea that, when properly “informed” of the relevant facts, scientifically literate citizens would immediately agree with experts is profoundly undemocratic: It belittles and erases all the relevant disagreements about values and rights. Such a view ignores, for instance, the fact that the dispute over GMO labeling has as much to do with ideas about citizens’ right to know and desire for transparency as the putative safety of GMOs. By acting as if such concerns do not matter – that only the outcome of recent safety studies do – the people sharing those concerns are deprived of a voice. The deficit model inexorably excludes those not working within a scientistic framework from democratic decision making. Given the deficit model’s democratic deficits as well as the lack of any evidence that scientific illiteracy is actually increasing, advocates of GMOs and other potentially risky instances of technoscience ought to look elsewhere for the sources of public scientific controversy. If anything has changed in the last decades it is that science and technology have less legitimacy. Indeed, science writers could better grasp this point by reading one of their own. Former Discover writer Robert Pool notes that the point of legal and regulatory challenges to new technoscience is not simply to render it safer but also more acceptable to citizens. Whether or not citizens accept a new technology depends upon the level of trust they have of technical experts (and the firms they work for). Opposition to GMOs, for instance, is partly rooted in the belief that private firms such as Monsanto cannot be trusted to adequately test their products and that the FDA and EPA are too toothless (or captured by industry interests) to hold such companies to a high enough standard. Technoscientists and cheerleading science writers are probably oblivious to the workings and requirements for earning public trust because they are usually biased to seeing new technologies as already (if not inherently) legitimate. Those deriding the public for failing to recognize the supposedly objective desirability of potentially risky technology, moreover, have fatally misunderstood the relationship between expertise, knowledge, and legitimacy. It is unreasonable to expect members of the public to somehow find the time (or perhaps even the interest) to learn about the nuances of genetic transmission or nuclear safety systems. Such expectations place a unique and unfair burden on lay citizens. Many technical experts, for instance, might be found to be equally ignorant of elementary distinctions in the social sciences or philosophy. Yet, few seem to consider such illiteracies to be equally worrisome barriers to a well-functioning democracy. In any case, as political scientists Joseph Morone and Edward Woodhouse argue, the position of the public is not to evaluate complex or arcane technoscientific problems directly but to decide which experts to trust to do so. Citizens, according to Morone and Woodhouse, were quite reasonable to turn against nuclear power when overoptimistic safety estimates were proven wrong by a series of public blunders, including accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, as well as increasing levels of disagreement among experts. Citizens’ lack of understanding of nuclear physics was beside the point: The technology was oversold and overhyped. The public now had good grounds to believe that experts were not approaching nuclear energy or their risk assessments responsibly. Contrary to the assumptions of deficit modelers, legitimacy is not earned simply through technical expertise but via sociopolitical demonstrations of trustworthiness. If technoscientific experts were to really care about democracy, they would think more deeply about how they could better earn legitimacy in the eyes of the public. At the very least, research in science and technology studies provides some guidance on how they ought not to proceed. For example, after post-Chernobyl accident radiation rained down on parts of Cumbria, England, scientists quickly moved in to study the effects as well as ensure that irradiated livestock did not get moved out of the area. Their behavior quickly earned them the ire of local farmers. Scientists not only ignored the relevant expertise that farmers had regarding the problem but also made bold pronouncements of fact that were later found to be false, including the claim that the nearby Sellafield nuclear processing plant had nothing to do with local radiation levels. The certainty with which scientists made their uncertain claims as well as their unwillingness to respond to criticism by non-scientists led farmers to distrust them. The scientists lost legitimacy as local citizens came to believe that they were sent there by the national government to stifle inquiry into what was going on rather than learn the facts of the matter. Far too many technoscientists (or at least their associated cheerleaders in popular media) seem content to repeat the mistakes of these Cumbrian radiation scientists. “Take your concerns elsewhere. The experts are talking,” they seem to say when non-experts raise concerns, “Come back when you’ve got a science degree.” Ironically (and tragically), experts’ embrace of deficit model understandings of public scientific controversies undermines the very mechanisms by which legitimacy is established. If the problem is really a deficit of public trust, diminishing the transparency of decisions and eliminating possibilities for citizen participation is self-defeating. Anything looking like a constructive and democratic resolution to controversies like GMOs, fracking, or nuclear energy is only likely to happen if experts engage with and seek to understand popular opposition. Only then can they begin to incrementally reestablish trust. Insofar as far too many scientists and other experts believe they deserve public legitimacy simply by their credentials – and some even denigrate lay citizens as ignorant rubes – public scientific controversies are likely to continue to be polarized and pathological. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed