It is hard to imagine anything more damaging to the movements for livable minimum wages, greater reliance on renewable energy resources, or workplace democracy than the stubborn belief that one must be a “liberal” to support them. Indeed, the common narrative that associates energy efficiency with left-wing politics leads to absurd actions by more conservative citizens. Not only do some self-identified conservatives intentionally make their pickup trucks more polluting at high costs (e.g., “rolling coal”) but they will shun energy efficient—and money saving— lightbulbs if their packaging touts their environmental benefits. Those on the left, often do little to help the situation, themselves seemingly buying into the idea that conservatives must culturally be everything leftists are not and vice-versa. As a result, the possibility to ally for common purposes, against a common enemy (i.e., neoliberalism), is forgone.

The Germans have not let themselves be hindered by such narratives. Indeed, their movement toward embracing renewables, which now make up nearly a third of their power generation market, has been driven by a diverse political coalition. A number villages in the German conservative party (CDU) heartland now produce more green energy than they need, and conservative politicians supported the development of feed-in tariffs and voted to phase out nuclear energy. As Craig Morris and Arne Jungjohann describe, the German energy transition resonates with key conservative ideas, namely the ability of communities to self-govern and the protection of valued rural ways of life. Agrarian villages are given a new lease on life by farming energy next to crops and livestock, and enabling communities to produce their own electricity lessens the control of large corporate power utilities over energy decisions. Such themes remain latent in American conservative politics, now overshadowed by the post-Reagan dominance of “business friendly” libertarian thought styles. Elizabeth Anderson has noticed a similar contradiction with regard to workplaces. Many conservative Americans decry what they see as overreach by federal and state governments, but tolerate outright authoritarianism at work. Tracing the history of conservative support for “free market” policies, she notes that such ideas emerged in an era when self-employment was much more feasible. Given the immense economies of scale possible with post-Industrial Revolution technologies, however, the barriers to entry for most industries are much too high for average people to own and run their own firms. As a result, free market policies no longer create the conditions for citizens to become self-reliant artisans but rather spur the centralization and monopolization of industries. Citizens, in turn, become wage laborers, working under conditions far more similar to feudalism than many people are willing to recognize. Even Adam Smith, to whom many conservatives look for guidance on economic policy, argued that citizens would only realize the moral traits of self-reliance and discipline—values that conservatives routinely espouse—in the right contexts. In fact, he wrote of people stuck doing repetitive tasks in a factory: “He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible to become for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life. Of the great and extensive interests of his country he is altogether incapable of judging”

Advocates of economic democracy have overlooked a real opportunity to enroll conservatives in this policy area. Right leaning citizens need not be like Mike Rowe—a man who ironically garnered a following among “hard working” conservatives by merely dabbling in blue collar work—and mainly bemoan the ostensible decline in citizens’ work ethic. Conservatives could be convinced that creating policies that support self-employment and worker-owned firms would be far more effective in creating the kinds of citizenry they hope for, far better than simply shaming the unemployed for apparently being lazy. Indeed, they could become like the conservative prison managers in North Dakota (1), who are now recognizing that traditionally conservative “tough on crime” legislation is both ineffective and fiscally irresponsible—learning that upstanding citizens cannot be penalized into existence.

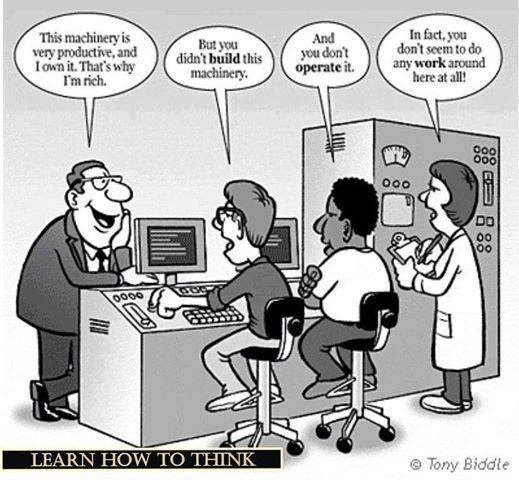

Another opportunity has been lost by not constructing more persuasive narratives that connect neoliberal policies with the decline of community life and the eroding well-being of the nation. Contemporary conservatives will vote for politicians who enable corporations to outsource or relocate at the first sign of better tax breaks somewhere else, while they simultaneously decry the loss of the kinds of neighborhood environments that they experienced growing up. Their support of “business friendly” policies had far different implications in the days when the CEO of General Motors would say “what is good for the country is good for General Motors and vice versa.” Compare that to an Apple executive, who baldly stated: “We don’t have an obligation to solve America’s problems. Our only obligation is making the best product possible.” Yet fights for a higher minimum wage and proposals to limit the destructively competitive processes where nations and cities try to lure businesses away from each other with tax breaks get framed as anti-American, even though they are poised to reestablish part of the social reality that conservatives actually value. Communities cannot prosper when torn asunder by economic disruptions; what is best for a multinational corporation is often not what is best for nation like the United States. It is a tragedy that many leftists overlook these narratives and focus narrowly on appeals to egalitarianism, a moral language that political psychologists have found (unsurprisingly) to resonate only with other leftists. The resulting inability to form alliances with conservatives over key economic and energy issues allows libertarian-inspired neoliberalism to drive conservative politics in the United States, even though libertarianism is as incompatible with conservativism as it is with egalitarianism. Libertarianism, by idealizing impersonal market forces, upholds an individualist vision of society that is incommensurable with communal self-governance and the kinds of market interventions that would enable more people to be self-employed or establish cooperative businesses. By insisting that one should “defer” to the supposedly objective market in nearly all spheres of life, libertarianism threatens to commodify the spaces that both leftists and conservatives find sacred: pristine wilderness, private life, etc. There are real challenges, however, to more often realizing political coalitions between progressives and conservatives, namely divisions over traditionalist ideas regarding gender and sexuality. Yet even this is a recent development. As Nadine Hubbs shows, the idea that poor rural and blue collar people are invariably more intolerant than urban elites is a modern construction. Indeed, studies in rural Sweden and elsewhere have uncovered a surprising degree of acceptance for non-hetereosexual people, though rural queer people invariably understand and express their sexuality differently than urban gays. Hence, even for this issue, the problem lies not in rural conservatism per se but with the way contemporary rural conservatism in America has been culturally valenced. The extension of communal acceptance has been deemphasized in order to uphold consistency with contemporary narratives that present a stark urban-rural binary, wherein non-cis, non-hetereosexual behaviors and identities are presumed to be only compatible with urban living. Yet the practice, and hence the narrative, of rural blue collar tolerance could be revitalized. However, the preoccupation of some progressives with maintaining a stark cultural distinction with rural America prevents progressive-conservative coalitions from coming together to realize mutually beneficial policy changes. I know that I have been guilty of that. Growing up with left-wing proclivities, I was guilty of much of what Nadine Hubbs criticizes about middle-class Americans: I made fun of “rednecks” and never, ever admitted to liking country music. My preoccupation with proving that I was really an “enlightened” member of the middle class, despite being a child of working class parents and only one generation removed from the farm, only prevented me from recognizing that I potentially had more in common with rednecks politically than I ever would with the corporate-friendly “centrist” politicians at the helm of both major parties. No doubt there is work to be done to undo all that has made many rural areas into havens for xenophobic, racist, and homophobic bigotry; but that work is no different than what could and should be done to encourage poor, conservative whites to recognize what a 2016 SNL sketch so poignantly illustrated: that they have far more in common with people of color than they realize. Note 1. A big oversight in the “work ethic” narrative is that it fails to recognize that slacking workers are often acting rationally. If one is faced with few avenues for advancement and is instantly replaced when suffering an illness or personal difficulties, why work hard? What white collar observers like Rowe might see as laziness could be considered an adaptation to wage labor. In such contexts, working hard can be reasonably seen as not the key to success but rather a product of being a chump. A person would be merely harming their own well-being in order to make someone else rich. This same discourse in the age of feudalism would have involved chiding peasants for taking too many holidays. 8/4/2014 Why Are Scientists and Engineers Content to Work for Scraps when MBAs get a Seat at the Table?Read Now Report from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Why should it be that some of the most brilliant and highly educated people I know are forced to beg for jobs and justify their work to managers who, in all likelihood, might have spent a greater part of their business program drunk than studying? Sure there are probably some useful tasks that managers and supervisors perform, and some of them are no doubt perfectly wonderful people. Nevertheless, why should they sit at the top of the hierarchy of the contemporary firm while highly skilled technologists just do what they are told? Why should those who design and build new technologies or solve tenacious scientific problems receive a wage and not a large share in the wealth they help generate? Most importantly, why do so many highly skilled and otherwise intelligent people put up with this situation? There is nothing natural about MBAs and other professional managers running a firm like a captain of ship. As Harvard economist Stephen Marglin illustrated so well, the emergence of that hierarchical system had little to do with improvements in technological efficiency or competitive superiority but rather that it better served the interests of capitalist owners. What bosses “do” is maximize the benefits accruing to capitalists at the expense of workers. Bosses have historically and continue to do this by minimizing the scope each individual worker has in the firm and inserting themselves (i.e., management) as the obligatory intermediary for even the most elementary of procedures. This allows them to better surveil and discipline workers for the benefit of owners. Most highly skilled workers will probably recognize this if they reflect on all those seemingly pointless memos they are forced to read and write. Of course, some separation of labor (and writing of memos) is necessary for achieving efficient production processes, but the current power arrangement ensures that exactly how any process ends up being partitioned is ultimately decided by and for the benefit of managers and owners prior to any consideration of workers’ interests.

Even if one were not bothered by the life-sucking monotony of many jobs inflicted by a strict separation of labor, there is still little reason why the person in charge of coordinating everyone’s individual tasks ought to rule with almost unquestioned authority. This is a particularly odd arrangement for tech firms, given that scientists and engineers are highly skilled workers whose creative talents make up the core the company’s success. Moreover, these workers only receive a wage while others (e.g., venture capitalists, shareholders and select managers) get the lion’s share of the generated wealth: “Thanks for writing the code for that app that made us millions. Here, have a bonus and count yourself lucky to have a job.” Although frequently taken to be “just the way things are,” it need not be the case that the totality of the profits of innovation so disproportionately accrue to shareholders and select managers. Neither does one need look as far away as socialist nations in order to recognize this. Family-owned and “closely held” corporations in the United States already forgo lower rates of monetary profit in order to enjoy non-monetary benefits and yet remain competitive. For instance, Hobby Lobby, recently made infamous for other reasons, closes its stores on Sundays. They give up sales to competitors like Michaels because those running the firm believe that workers ought to have a guaranteed day in their schedule to spend time with friends and loved ones. Companies like Chick-Fil-A, Wegman’s and others pay their workers more livable wages and/or help fund their college educations, all practices unlikely to maximize shareholder value by any stretch of the imagination. At the same time, the hiring process for many managers does not lend much credence to the view that their skills alone make the difference between a successful or unsuccessful company. Michael Church, for instance, recently posted an account of the differences between applying to tech firm as a software engineer versus a manager. When interviewing as a software engineer, the applicant was subjected to a barrage of doubts about their skills and qualifications. The burden of proof was laid on the applicant to prove themselves worthy. In contrast, when applying for a management position, the same applicant was seen as “already part of the club” and was targeted with hardly any scrutiny at all. This is, of course, but one example. I encourage readers to share their own experiences in the comments section. Regardless, I suspect that if management is regularly treated like a club for those with the right status rather than the right competencies, their skills may not be so scarce or essential as to justify their higher wages, stake in company assets and discretion in decision-making. Young, highly skilled workers seem totally unaware of the power they could have in their working lives, if enough of them strove to seize it. I am not talking about unionization, though that could also be helpful. Instead, I am suggesting that scientists and engineers could own and manage their own firms, reversing (or simply leveling) the hierarchy with their current business-major overlords. Doing so would not be socialism but rather economic democracy: a worker cooperative. Workers outside the narrow echelon of managers and distant venture capitalists could have stake in the ownership of capital and thus power in the firm, making it much more likely that their interests are better reflected in decisions about operations and longer-term business plans. There is no immediately obvious reason why scientists and engineers could not start their own worker cooperatives. In fact, there are cases of workers less skilled and educated than the average software engineer helping govern and earning equity in their companies. The Evergreen cooperative in Cleveland, Ohio, for instance, consists of a laundry – mostly serving a nearby hospital, a greenhouse and a weatherization contractor. A small percentage of each worker’s salary goes into owning a stake in the cooperative, amounting to about $65,000 in wealth in roughly eight years. Workers elect their own representation to the firm’s board and thus get a say in its future direction and daily operation. Engineers, scientists and other technologists are intelligent enough to realize that the current “normal” business hierarchy offers them a raw deal. If laundry workers and gardeners can cooperatively run a profitable business while earning wealth, not merely a wage, certainly those with the highly specialized, creative skills always being extolled as being the engine of the “new knowledge economy” could as well. The main barrier is psychological. Engineers, scientists and other technologists have been encultured to think that things work out best if they remain mere problem solvers – more cynical observers might say overhyped technicians. Maybe they believe they will be one of the lucky ones to work somewhere with free pizza, breakout rooms and a six figure salary, or maybe they think they will eventually break into management themselves. Of course there is also the matter of the start-up capital that any tech firm needs to get off the ground. Yet, if enough technologists started their own cooperative firms, they could eventually pool resources to finance the beginnings of other cooperative ventures. All it would take is a few dozen enterprising people to show their peers that they do not have to work for scraps (even if there are sometimes large paychecks to go with that free pizza). Rather, they could take a seat at the table. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed