|

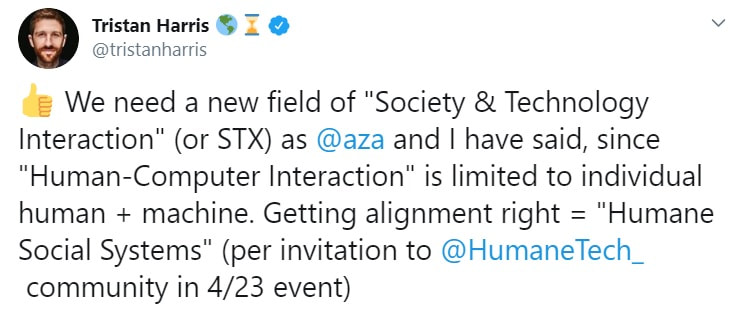

Back during the summer, Tristan Harris sparked a flurry of academic indignation when he suggested that we needed a new field called “Science & Technology Interaction” or STX, which would be dedicated to improving the alignment between technologies and social systems. Tweeters were quick to accuse him of “Columbizing,” claiming that such a field already existed in the form of Science & Technology Studies (STS) or similar such academic department. So ignorant, amirite?

I am far more sympathetic. If people like Harris (and earlier Cathy O’Neil) have been relatively unaware of fields like Science and Technology Studies, it is because much of the research within these disciplines is mostly illegible to non-academics, not all that useful to them, or both. I really don’t blame them for not knowing. I am even an STS scholar myself, and the table of contents of most issues of my field’s major journals don’t really inspire me to read further. And in fairness to Harris and contrary to Academic Twitter, the field of STX that he proposes does not already exist. The vast majority of STS articles and books dedicate single digit percentages of their words to actually imagining how technology could better match the aspirations of ordinary people and their communities. Next to no one details alternative technological designs or clear policy pathways toward a better future, at least not beyond a few pages at the end of a several-hundred-page manuscript. My target here is not just this particular critique of Harris, but the whole complex of academic opiners who cite Foucault and other social theory to make sure we know just how “problematic” non-academics’ “ignorant” efforts to improve technological society are. As essential as it is to try to improve upon the past in remaking our common world, most of these critiques don’t really provide any guidance for what steps we should be taking. And I think that if scholars are to be truly helpful to the rest of humanity they need to do more than tally and characterize problems in ever more nuanced ways. They need to offer more than the academic equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. In the case of Harris, we are told that underlying the more circumspect digital behavior that his organization advocates is a dangerous preoccupation with intentionality. The idea of being more intentional is tainted by the unsavory history of humanistic thought itself, which has been used for exclusionary purposes in the past. Left unsaid is exactly how exclusionary or even harmful it remains in the present. This kind of genealogical take down has become cliché. Consider how one Gizmodo blogger criticizes environmentalists’ use the word “natural” in their political activism. The reader is instructed that because early Europeans used the concept of nature to prop up racist ideas about Native Americans that the term is now inherently problematic and baseless. The reader is supposed to believe from this genealogical problematization that all human interactions with nature are equally natural or artificial, regardless of whether we choose to scale back industrial development or to erect giant machines to control the climate. Another common problematiziation is of the form “not everyone is privileged enough to…”, and it is often a fair objection. For instance, people differ in their individual ability to disconnect from seductive digital devices, whether due to work constraints or the affordability or ease of alternatives. But differences in circumstances similarly challenge people’s capacity to affordably see a therapist, retrofit their home to be more energy efficient, or bike to work (and one might add to that: read and understand Foucault). Yet most of these actions still accomplish some good in the world. Why is disconnection any more problematic than any other set of tactics that individuals use to imperfectly realize their values in an unequal and relatively undemocratic society? Should we just hold our breaths for the “total overhaul…full teardown and rebuild” of political economies that the far more astute critics demand? Equally trite are references to the “panopticon,” a metaphor that Foucault developed to describe how people’s awareness of being constantly surveilled leads them to police themselves. Being potentially visible at all times enables social control in insidious ways. A classic example is the Benthamite prison, where a solitary guard at the center cannot actually view all the prisoners simultaneously, but the potential for him to be viewing a prisoner at any given time is expected to reduce deviant behavior. This gets applied to nearly any area of life where people are visible to others, which means it is used to problematize nearly everything. Jill Grant uses it to take down the New Urbanist movement, which aspires (though fairly unsuccessfully) to build more walkable neighborhoods that are supportive of increased local community life. This movement is “problematic” because the densities it demands means that citizens are everywhere visible to their neighbors, opening up possibilities for the exercise of social control. Whether not any other way of housing human beings would not result in some form of residential panopticon is not exactly clear, except perhaps by designing neighborhoods so as to prohibit social community writ large. Further left unsaid in these critiques is exactly what a more desirable alternative would be. Or at least that alternative is left implicit and vague. For example, the pro-disconnection digital wellness movement is in need of enhanced wokeness, to better come to terms with “the political and ideological assumptions” that they take for granted and the “privileged” values they are attempting to enact in the world. But what does that actually mean? There’s a certain democratic thrust to the criticism, one that I can get behind. People disagree about what is “the good life” and how to get there, and any democratic society would be supportive of a multitude of them. Yet the criticism that the digital wellness movement seems to center around one vision of “being human,” one emphasizing mindfulness and a capacity to exercise circumspect individual choosing, seems hollow without the critics themselves showing us what should take its place. Whatever the flaws with digital wellness, it is not as self-stultifying as the defeatist brand of digital hedonism implicitly left in the wake of academic critiques that offer no concrete alternatives. Perhaps it is unfair to expect a full-blown alternative; yet few of these critiques offer even an incremental step in the right direction. Even worse, this line of criticism can problematize nearly everything, losing its rhetorical power as it is over-applied. Even academia itself is disciplining. STS has its own dominant paradigms, and critique is mobilized in order to mold young scholars into academics who cite the right people, quote the correct theories, and support the preferred values. My success depends on me being at least “docile enough” in conforming myself to the norms of the profession. I also exercise self-discipline in my efforts to be a better spouse and a better parent. I strive to be more intentional when I’m frustrated or angry, because I too often let my emotions shape my interactions with loved ones in ways that do not align with my broader aspirations. More intentionality in my life has been generally a good thing, so long as my expectations are not so unrealistic as to provoke more anxiety than the benefits are worth. But in a critical mode where self-discipline and intentionality automatically equate to self-subjugation, how exactly are people to exercise agency in improving their own lives? In any case, advocating devices that enable users to exercise greater intentionality over their digital practices is not a bad thing per se. Citizens pursue self-help, meditate, and engage in other individualistic wellness activities because the lives they live are constrained. Their agency is partly circumscribed by their jobs, family responsibilities, and incomes, not to mention the more systemic biases of culture and capitalism. Why is it wrong for groups like Harris’ center to advocate efforts that largely work within those constraints? Yet even that reading of the digital wellness movement seems uncharitable. Certainly Harris’ analysis lacks the sophistication of a technology scholar’s, but he has made it obvious that he recognizes that dominant business models and asymmetrical relations of power underlay the problem. To reduce his efforts to mere individualistic self-discipline is borderline dishonest, though he no doubt emphasizes the parts of the problem he understands best. Of course it will likely take more radical changes to realize the humane technology than Harris advocates, but it is not totally clear whether individualized efforts necessarily detract from people’s ability or the willingness demand more from tech firms and governments (i.e., are they like bottled water and other “inverted quarantines”?). At least that is a claim that should be demonstrated rather than presumed from the outset. At its worst, critical “problematizing” presents itself as its own kind of view from nowhere. For instance, because the idea of nature has been constructed in various biased throughout history, we are supposed to accept the view that all human activities are equally natural. And we are supposed to view that perspective as if it were itself an objective fact rather than yet another politically biased social construction. Various observers mobilize much the same critique about claims regarding the “realness” of digital interactions. Because presenting the category of “real life” as being apart from digital interactions is beset with Foulcauldian problematics, we are told that the proper response is to no longer attempt the qualitative distinctions that that category can help people make—whatever its limitations. It is probably no surprise that the same writer wanting to do away with the digital-real distinction is enthusiastic in their belief that the desires and pleasures of smartphones somehow inherently contain the “possibility…of disrupting the status quo.” Such critical takes give the impression that all technology scholarship can offer is a disempowering form of relativism, one that only thinly veils the author’s underlying political commitments. The critic’s partisanship is also frequently snuck in the backdoor by couching criticism in an abstract commitment to social justice. The fact that the digital wellness movement is dominated by tech bros and other affluent whites implies that it must be harmful to everyone else—a claim made by alluding to some unspecified amalgamation of oppressed persons (women, people of color, or non-cis citizens) who are insufficiently represented. It is assumed but not really demonstrated that people within the latter demographics would be unreceptive or even damaged by Harris’ approach. But given the lack of actual concrete harms laid out in these critiques, it is not clear whether the critics are actually advocating for those groups or that the social-theoretical existence of harms to them is just a convenient trope to make a mainly academic argument seem as if it actually mattered. People’s prospects for living well in the digital age would be improved if technology scholars more often eschewed the deconstructive critique from nowhere. I think they should act instead as “thoughtful partisans.” By that I mean that they would acknowledge that their work is guided by a specific set of interests and values, ones that are in the benefit of particular groups. It is not an impartial application of social theory to suggest that “realness” and “naturalness” are empty categories that should be dispensed with. And a more open and honest admission of partisanship would at least force writers to be upfront with readers regarding what the benefits would actually be to dispensing with those categories and who exactly would enjoy them—besides digital enthusiasts and ecomodernists. If academics were expected to use their analysis to the clear benefit of nameable and actually existing groups of citizens, scholars might do fewer trite Foucauldian analyses and more often do the far more difficult task of concretely outlining how a more desirable world might be possible. “The life of the critic easy,” notes Anton Ego in the Pixar film Ratatouille. Actually having skin in the game and putting oneself and one’s proposals out in the world where they can be scrutinized is far more challenging. Academics should be pushed to clearly articulate exactly how it is the novel concepts, arguments, observations, and claims they spend so much time developing actually benefit human beings who don’t have access to Elsevier or who don't receive seasonal catalogs from Oxford University Press. Without them doing so, I cannot imagine academia having much of a role in helping ordinary people live better in the digital age. Few issues stoke as much controversy, or provoke as shallow of analysis, as net neutrality. Richard Bennett’s recent piece in the MIT Technology Review is no exception. His views represent a swelling ideological tide among certain technologists that threatens not only any possibility for democratically controlling technological change but any prospect for intelligently and preemptively managing technological risks. The only thing he gets right is that “the web is not neutral” and never has been. Yet current “net neutrality” advocates avoid seriously engaging with that proposition. What explains the self-stultifying allegiance to the notion that the Internet could ever be neutral?

Bennett claims that net neutrality has no clear definition (it does), that anything good about the current Internet has nothing to do with a regulatory history of commitment to net neutrality (something he can’t prove), and that the whole debate only exists because “law professors, public interest advocates, journalists, bloggers, and the general public [know too little] about how the Internet works.” To anyone familiar with the history of technological mistakes, the underlying presumption that we’d be better off if we just let the technical experts make the “right” decision for us—as if their technical expertise allowed them to see the world without any political bias—should be a familiar, albeit frustrating, refrain. In it one hears the echoes of early nuclear energy advocates, whose hubris led them to predict that humanity wouldn’t suffer a meltdown in hundreds of years, whose ideological commitment to an atomic vision of progress led them to pursue harebrained ideas like nuclear jets and using nuclear weapons to dig canals. One hears the echoes of those who managed America’s nuclear arsenal and tried to shake off public oversight, bringing us to the brink of nuclear oblivion on more than one occasion. Only armed with such a poor knowledge of technological history could someone make the argument that “the genuine problems the Internet faces today…cannot be resolved by open Internet regulation. Internet engineers need the freedom to tinker.” Bennett’s argument is really just an ideological opposition to regulation per se, a view based on the premise that innovation better benefits humanity if it is done without the “permission” of those potentially negatively affected. Even though Bennett presents himself as simply a technologist whose knowledge of the cold, hard facts of the Internet leads him to his conclusions, he is really just parroting the latest discursive instantiation of technological libertarianism. As I’ve recently argued, the idea of “permissionless innovation” is built on a (intentional?) misunderstanding of the research on how to intelligently manage technological risks as well as the problematic assumption that innovations, no matter how disruptive, have always worked out for the best for everyone. Unsurprisingly the people most often championing the view are usually affluent white guys who love their gadgets. It is easy to have such a rosy view of the history of technological change when one is, and has consistently been, on the winning side. It is a view that is only sustainable as long as one never bothers to inquire into whether technological change has been an unmitigated wonder for the poor white and Hispanic farmhands who now die at relatively younger ages of otherwise rare cancers, the Africans who have mined and continue to mine Uranium or coltan in despicable conditions, or the permanent underclass created by continuous technological upheavals in the workplace not paired with adequate social programs. In any case, I agree with Bennett’s argument in a later comment to the article: “the web is not neutral, has never been neutral, and wouldn't be any good if it were neutral.” Although advocates for net neutrality are obviously demanding a very specific kind of neutrality: that ISPs do not treat packets differently based on where they originate or where they’re going, the idea of net neutrality has taken on a much broader symbolic meaning, one that I think constrains people’s thinking about Internet freedoms rather than enhances it. The idea of neutrality carries so much rhetorical weight in Western societies because their cultures are steeped in a tradition of philosophical liberalism. Liberalism is a philosophical tradition based in the belief that the freedom of individuals to choose is the greatest good. Even American political conservatives really just embrace a particular flavor of philosophical liberalism, one that privileges the freedoms enjoyed by supposedly individualized actors unencumbered by social conventions or government interference to make market decisions. Politics in nations like the US proceeds with the assumption that society, or at least parts of it, can be composed in such a way to allow individuals to decide wholly for themselves. Hence, it is unsurprising that changes in Internet regulations provoke so much ire: The Internet appears to offer that neutral space, both in terms of the forms of individual self-expression valued by left-liberals and the purportedly disruptive market environment that gives Steve Jobs wannabes wet dreams. Neutrality is, however, impossible. As I argue in my recent book, even an idealized liberal society would have to put constraints on choice: People would have to be prevented from making their relationship or communal commitments too strong. As loathe as some leftists would be to hear it, a society that maximizes citizens’ abilities for individual self-expression would have to be even more extreme than even Margaret Thatcher imagined it: composed of atomized individuals. Even the maintenance of family structures would have to be limited in an idealized liberal world. On a practical level it is easy to see the cultivation of a liberal personhood in children as imposed rather than freely chosen, with one Toronto family going so far as to not assign their child a gender. On plus side for freedom, the child now has a new choice they didn’t have before. On the negative side, they didn’t get to choose whether or not they’d be forced to make that choice. All freedoms come with obligations, and often some people get to enjoy the freedoms while others must shoulder the obligations. So it is with the Internet as well. Currently ISPs are obliged to treat packets equally so that content providers like Google and Netflix can enjoy enormous freedoms in connecting with customers. That is clearly not a neutral arrangement, even though it is one that many people (including Google) prefer. However, the more important non-neutrality of the Internet, one that I think should take center stage in debates, is that it is dominated by corporate interests. Content providers are no more accountable to the public than large Internet service providers. At least since it was privatized in the mid-90s, the Internet has been biased toward fulfilling the needs of business. Other aspirations like improving democracy or cultivating communities, if the Internet has even really delivered all that much in those regards, have been incidental. Facebook wants you to connect with childhood friends so it can show you an ad for a 90s nostalgia t-shirt design. Google wants to make sure neo-nazis can find the Stormfront website so they can advertise the right survival gear to them. I don’t want a neutral net. I want one biased toward supporting well-functioning democracies and vibrant local communities. It might be possible for an Internet to do so while providing the wide latitude for innovative tinkering that Bennett wants, but I doubt it. Indeed, ditching the pretense of neutrality would enable the broader recognition of the partisan divisions about what the Internet should do, the acknowledgement that the Internet is and will always be a political technology. Whose interests do you want it to serve? Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered

Opponents of regulatory changes that could mean the end of “net neutrality” or proposed legislation like the SOPA/PIPA acts of 2012 regularly contend that these policies would “break the Internet” in some significant way. They prophesize that such measures will lead to an Internet rotten to the core by political censorship or one less generative of creativity. Those on the other side, in response, turn out their own expert analysis meant to assure citizens that the intangible goods purportedly offered by the Internet – such as greater democracy or “innovation” writ large – are not really being undermined at all. In the continuous back and forth between these opposing sides, rarely is the question of whether or not “breaking” the contemporary Internet is actually undesirable given much thought or analysis. It is presumed rather than demonstrated that the current Web “works.” What reasons might we have to consider letting ISPs and content creators lead public policy toward a “broken” Net? Is the contemporary Internet really all that worth saving? To begin, there are grounds for wondering if the Internet has really been that much of a boon to democracy. Certainly critics like Hindman andMorozov – who point out how infrequently political concerns occupy web surfers, how most content production is dominated by a few elites, and that the Internet has had an ambivalent role in promoting enhanced democracy in totalitarian regimes – would likely warn against overestimating the actual democratic utility of contemporary digital networks. Arab Spring notwithstanding, the Internet seems to play as big a role in entertainment, “clicktivism” and commerce driven pacification of populations as their liberation. Though undoubtedly useful for activists needing a tool for organizing popular action across space and time, the Web is also a major vehicle for the “bread and circuses” (i.e., Amazon purchases and Netflix marathons) that too frequently aid citizen passivity. Moreover, as Jodi Dean points out, those championing the ostensible democratic properties of digital networks frequently overstate the political gains afforded by certain means for public communicative self-expression becoming “democratized.” Just because the Average Joe (or Jane) can now publish their own blog does not necessary mean that they have any more influence on public policy than before. Second, the image of the Internet as a bottom-up, decentralized and people-powered technology of liberation, for all intents and purposes, seems to be more myth than reality. From the physical infrastructure and the standardization of protocols to the provision of content through websites like Google and Facebook, the Internet is highly centralized and very often already steered by the interests of large corporations. Media scholars Robert McChesney and John Nichols, for instance, contend that the Internet has been one of the greatest drivers of economic monopoly in history. Likewise the depiction of the movement against measures that threaten net neutrality as strictly the bottom-up voice of the people is similarly a figment of collective imagination. That this opposition has any political traction has more to do with the fact that content providers like Netflix and others having a major financial stake in a non-tiered Internet than the bubbling over of popular democratic ferment. Purveyors of bandwidth hungry services profit greatly from a neutral net at the expense of ISPs, who, in turn, are looking for a bigger piece of the pie for themselves. Third, as Ethan Zuckerman has recently pointed out in an article for the Atlantic, the entrenched status-quo business model of the Internet is advertising. Getting an edge over the competition in advertising requires more effectively surveilling users. We have unintelligently steered ourselves to a Net that financially depends on users’ surfing and social activities being constantly tracked, monitored and analyzed. Users’ provision of “free cultural labor” to companies like Google and Facebook drives the contemporary Internet. The fact that the current Web depends so intimately on advertising, moreover, fuels “clickbait” journalism (think Upworthy), malware and high levels of economic centralization. Facebook’s acquiring of Instagram, as Zuckerman reminds us, was motivated by the company’s desire to maintain its demographic reach of advertising data points and targets. Size, and thereby access to big data, generally wins the day in an ad-driven Internet. Finally, for those of us who wish contemporary technological civilization offered more frequent opportunities for realizing vibrant face-to-face community, the Internet is more often “good enough” than a godsend. A Facebook homefeed or Netflix marathon provides a minimally satisfying substitute for the social connection and storytelling that occurred within local pubs, cafés and other civic institutions, spaces that centered community life at other times and places. Consider one stay-at-home mom’s recent blogging about the loneliness of contemporary motherhood, loneliness that she describes as persisting despite the much hyped connection offered by Facebook and other social networks. She recounts driving to Target just to feel the presence of other people, seeing fellow mothers but ultimately lacking the nerve to say what she feels: “Are you lonely too?… Can we be friends? Am I freaking you out? I don’t care. HOLD ME.” Digitally mediated contact and networked social “meetups” are means to social intimacy that many of us accept reluctantly. They are, at best, anodynes for the pain caused by all the barriers standing in the way of embodied communality: suburbia, gasoline prices, six-dollar pints of beer, and the fact that too many of us long ago became habituated to being homebodies and public-space introverts. The fact that the contemporary Web has these strikes against it, of course, does not necessarily mean that is better to break it than reform it. That claim hinges on the degree to which these facets of the Internet are entrenched and likely to strongly resist change. Are thin democracy, weak community and corporate dominance already obdurate features of the Net? Has the technology gained so much sociotechnical momentum that it seems unreasonable to expect anything better out of it? If the answer to these questions is “Yes,” then citizens have good reason for believing that the most desirable avenue for “moving forward” is the abandonment of the contemporary Internet. I am not first to suggest this course of action. A former champion of the Internet, Douglas Rushkoff , now advocates its abandonment in order to focus on building alternatives through mesh-network technologies. Mesh-networks are potentially advantageous in that surveillance is more difficult, they are structurally decentralized and appear to offer better opportunities for collective control and governance. Experimental community mesh networks are already up and running in Spain, Germany and Greece. If properly steered, they could be an integral part of the development of more substantively democratic and communitarian Internets. If that is truly the case, then resources currently being dedicated to fighting for net neutrality might be put to better use supporting experimentation with and the building of mesh-network alternatives to the current Internet. Letting ISPs have their way in the net neutrality debate, therefore, could prove to be a good thing. Users frustrated by increasing fees and choppy Netflix feeds are going to be more likely to be interested in Web alternatives than those with near perfect service. For the case of the Internet and improved democracy/community, perhaps letting things get worse is the only way they will ever get any better. In my last post, I considered some of the consequences of instantly available and seemingly endless quantities of Internet-driven novelty for the good life, particularly in the areas of story and joke telling as well as how we converse and think about our lives. This week, I want to focus more on the challenges to willpower exacerbated by Internet devices. Particularly, I am concerned with how today’s generation of parents, facing their own particular limitations of will, may be encouraging their children to have a relationship with screens that might be best described as fetishistic. My interest is not merely with the consequences for learning, although psychological research does connect media-multitasking with certain cognitive and memory deficits. Rather, I am worried about the ways in which some technologies too readily seduce their users into distracted and fragmented ways of living rather than enhancing their capacity to pursue the good life.

A recent piece in Slate overviews much of recent research concerning the negative educational consequences of media multitasking. Unsurprisingly, students who allowed their focus to be interrupted by a text or some other digital task, whether in lecture or studying, perform significantly worse. The article, more importantly, notes the special challenge that digital devices pose to self-discipline, suggesting that such devices are the contemporary equivalent to the “marshmallow test.” The Stanford marshmallow experiment was a series of longitudinal studies that found children's capacity to delay gratification to be correlated with their later educational successes and body-mass index, among other factors. In the case of these experiments, children were rated according their ability to forgo eating a marshmallow, pretzel or cookie sitting in front of them in order to obtain two later on. Follow-up studies have shown that this capacity for self-discipline is likely as much environmental as innate; children in “unreliable environments,” where experimenters would make unrelated promises and then break them, exhibited a far lower ability to wait before succumbing to temptation. The reader may reasonably wonder at this point, what do experiments tempting children with marshmallows have to do with iPhones? The psychologist Roy Baumeister argues that the capacity to exert willpower behaves like a limited resource, generally declining after repeated challenges. By recognizing this aspect of human self-discipline, the specific challenge of device-driven novelty is clearer. Today, more and more time and effort must be expended in exerting self-control over various digital temptations, more quickly depleting the average person's reserves of willpower. Of course, there are innumerable non-digital temptations and distractions that people are faced with everyday, but they are of a decidedly different character. I can just as easily shirk by reading a newspaper. At some point, however, I run out of articles. The particular allure of a blinking email notice or instant message that always seems to demand one’s immediate attention cannot be discounted either. Although it is not yet clear what the broader effects of pervasive digital challenges to willpower and self-discipline will be, other emerging practices will likely only exacerbate the consequences. The portability of contemporary digital devices, for instance, has enabled the move from “TV as babysitter” to media tablet as pacifier. A significant portion of surveyed parents admit to using a smart phone or iPad in order to distract their children at dinners and during car rides. Parents, of course, should not bear all of the blame for doing so; they face their own limits to willpower due to their often hectic and stressful working lives. Nevertheless, this practice is worrisome not only because it fails to teach children ways of occupying themselves that do not involve staring into a screen but also since the device is being used foremost as a potentially pathological means of pacification. I have observed a number of parents stuffing a smart phone in their child’s face to prevent or stop a tantrum. While doing so is usually effective, I worry about the longer term consequences. Using a media device as the sole curative to their children’s’ emotional distress and anxiety threatens to create a potentially fetishistic relationship between the child and the technology. That is, the tablet or smart phone becomes like a security blanket – an object that allays anxiety; it is a security blanket, however, that the child does not have give up as he or she gets older. This sort of fetishism has already become fodder for cultural commentary. In the television show “The Office,” the temporary worker named Ryan generally serves as a caricature of the millennial generation. In one episode, he leaves his co-workers in the lurch during a trivia contest after being told he cannot both have his phone and participate. Forced to decide between helping his colleagues win the contest and being able to touch his phone, Ryan chooses the latter. This is, of course, a fictional example but, I think, not too unrealistic a depiction of the likely emotional response. I am unsure if many of the college students I teach would not feel a similar sort of distress if (forcibly) separated from their phones. This sort of affect-rich, borderline fetishistic, connection with a device can only make more difficult the attempt to live in any way other than by the device’s own logic or script. How easily can users resist the distractions emerging from a technological device that comes to double as their equivalent to a child’s security blanket? Yet, many of my colleagues would view my concerns about people’s capacities for self-discipline with suspicion. For those having read (perhaps too much) Michel Foucault, notions of self-discipline tend to be understood as a means for the state or some other powerful entity to turn humans into docile subjects. In seminar discussions, places like gyms are often viewed as sites of self-repression first and promoting of physical well-being second. There is, to be fair, a bit of truth to this. Much of the design of early compulsory schooling, for instance, was aimed at producing diligent office and factory workers who followed the rules, were able to sit still for hours and could tolerate both rigid hierarchies and ungodly amounts of tedium. Yet, just because the instilling of self-discipline can be convenient for those who desire a pacified populace does not mean it is everywhere and always problematic. The ability to work for longer than five minutes without getting distracted is a useful quality for activists and the self-employed to have as well; self-discipline is not always self-stultifying. Indeed, it may be the skill needed most if one is to resist the pull of contemporary forms of control, such as advertising. The last point is one of the critical oversights of many post-modern theorists. So concerned they are about forms of policing and discipline imposed by the state that they overlook how, as Zygmunt Bauman has also pointed out, humans are increasingly integrated into today’s social order through seduction rather than discipline, advertising rather than indoctrination. Fears about potentials for a 1984 can blind one to the realities of an emerging Brave New World. Being pacified by the equivalent of soma and feelies is, in my mind, no less oppressive than living under the auspices of Big Brother and the thought police. Viewed in light of this argument, the desire to “disconnect” can be seen not the result of an irrational fear of the digital but is made in recognition of the particular seductive challenges that it poses for human decision making. Too often, scholars and layperson alike tend to view technological civilization through the lens of “technological liberalism,” conceptualizing technologies as simply tools that enhance and extend the individual person’s ability to choose their own version of the good life. Insofar as a class of technologies increasingly enable users to give into their most base and unreflective proclivities – such as enabling endless distraction into a largely unimportant sea of videos, memes and trivia, they seem to enhance neither a substantive form of choice nor the good life. In a dark room sits a man at his computer. Intensely gazing at the screen, he lets the images and videos wash over him. He is on the hunt for just the right content to satisfy him. Expressing a demeanor of ennui alternating with short-lived arousal, he hurriedly clicks through pages, links and tabs. He is tired. He knows he should just get it over with and go to bed. Yet, each new piece of information is attention-grabbing in a different way and evokes a sense of satisfaction – small pleasures, however, tinged with a yearning for still more. At last, he has had enough. Spent. Looking at the clock, he cannot help but feel a little disappointed. Three hours? Where did all the time go? Somewhat disgusted with himself, he lies in bed and eventually falls asleep. This experience is likely familiar to many Internet users. The hypothetical subject that I described above could have been browsing for anything really: cat videos, pornography, odd news stories, Facebook updates or symptoms of a disorder he may or may not actually have. Through it, I meant to illustrate a common practice that one could call “novelty bingeing,” an activity that may not be completely new to the human condition but is definitely encouraged and facilitated by Internet technologies. I am interested in what such practices mean for the good life. However, there is likely no need for alarmism. The risks of chronic, technologically-supported pursuit of novelty and neophilia are perhaps more likely to manifest in a numbing sense of malaise than some dramatic crisis.

Nicholas Carr, of course, has already written a great deal about his worries that many of the informational practices enabled and encouraged in surfing the Internet may be making users shallower thinkers. Research at Stanford has confirmed that chronic media multitasking appears to have lasting, negative consequences on cognitive ability. Carr is concerned that Western humanity risks slowly and collectively forgetting how to do the kind of thinking seemingly better afforded by reading in one’s living room or walking in natural environments less shaped and infiltrated by industrial and digital technologies. To the extent that more linear and more meditative forms of mental activity are valuable for living well, typical Internet practices appear to stand in the way of the good life. One must, however, consider the trade-offs: Are the barriers to greater concentration and slower, meditative thinking worth the gains? Curiosity and neophilia are part of and parcel, in some sense, to intellectual activity writ large. Humans’ brains are attuned to novelty in order to help them understand their environments. On occasion, my own browsing of blogs and random articles has spurred thoughts that I may not have otherwise had, or at least at that moment. So it is not novelty-seeking, neophilia, in general that may be problematic for the practice of deep, broad thinking but the pursuit of decontextualized novelty for novelty’s sake. If the design of various contemporary Internet technologies can be faulted, it is for failing to provide a supporting structure for contextualizing novelty so that it does not merely serve as a pleasant distraction but also aids in the understanding of one’s own environment; in a sense, that responsibility, perhaps even burden, is shifted evermore onto users. Yet, to only consider the effects of Internet practices on cognitive capacities, I think, is to cast one’s net too narrowly. Where do affect and meaning fit into the picture? I think a comparison with practices of consumerism or materialistic culture is apt. As scholars such as Christopher Lasch have pointed out, consumerism is also driven by the endless pursuit of novelty. Yet, digital neophilia has some major differences; the object being consumed is an image, video or text that only exists for the consumer as long as it is visible on the screen or is stored on a hard-drive, and such non-material consumables seldom require a monetary transaction. It is a kind of consumerism without physical objects, a practice of consuming without purchasing. As a result, many of the more obvious “bads” of consumer behavior no longer applicable, such as credit card debt and the consumer’s feeling that their worth is dependent on their purchasing power. Baudrillard described consumerist behavior as the building up of a selfhood via a “system of objects.” That is, objects are valued not so much for their functional utility but as a collection of symbols and signs representing the self. Consumerism is the understanding of “being” as tantamount to “having” rather than “relating.” Digital neophilia, on the other hand, appears to be the building up of the self around a system of observations. Many heavy Internet users spend hours each day flitting from page to page and video to video; one shares in the spreading and viewing of memes in a way that parallels the sharing and chasing of trends in fashion and consumer electronics. Of which kind of “being” might such an immense investment of time and energy into pursuing endlessly-novel digital observations be in service? Unfortunately, I know of no one directly researching this question. I can only begin to surmise a partial answer from tangential pieces of evidence. The elephant of the room is whether such activity amounts to addiction and if calling it such aids or hinders our understanding of it. The case I mentioned in my last post, the fact that Evegny Morozov locks up his wi-fi card in order to help him resist the allure of endless novelty, suggests that at least some people display addictive behavior with respect to the Net. One of my colleagues, of course, would likely warn me of the risks in bandying about the word “addiction.” It has been often used merely to police certain forms of normality and pathologize difference. Yet, I am not convinced the word wholly without merit. Danah boyd, of all people, has worried that “we’re going to develop the psychological equivalent of obesity,” if we are not mindful concerning how we go about consuming digital content; too often we use digital technologies to pursue celebrity and gossip in ways that do not afford us “the benefits of social intimacy and bonding.” Nevertheless, the only empirical research I could find concerning the possible effects of Internet neophilia was in online pornography studies; research suggests that the viewing of endlessly novel erotica leads some men to devalue their partners in a way akin to how advertising might encourage a person to no longer appreciate their trusty, but outmoded, wardrobe. This result is interesting and, if the study is genuinely reflective of reality for a large number of men in committed relationships, worrisome.[1] At the same time, it may be too far a leap to extrapolate the results to non-erotic media forms. Does digital neophilia promote feelings of dissatisfaction with one’s proximate, everyday experiences because they fail to measure up with those viewed via online media? Perhaps. I generally find that many of my conversations with people my own age involve more trading of stories about what one has recently seen on YouTube than stories about oneself. I hear fewer jokes and more recounting of funny Internet skits and pranks, which tend to involve people no one in the conversation actually knows. Although social media and user-generated content has allowed more people to be producers of media, it is seems to have simultaneously amplified the consumption behavior of those who continue to not produce content. To me, this suggests that, at some level, many people are increasingly encouraged to think their lives are less interesting then what they find online. If they did not view online spaces as the final arbiters of what information is interesting or worthy enough to tell others, why else would so many people feel driven to tweet or post a status update any time something the least bit interesting happens to them but feel disinclined to proffer much of themselves or their own experiences in face-to-face conversation? I might be slightly overstating my case, but I believe the burden of evidence ought to fall on Internet-optimists. Novelty-bingeing may not be an inherent or essential characteristic of information technologies for all time, but, for the short-term, it is a dominant feature on the Net. The various harms may be subtle and difficult to measure, but it is evident in the obvious efforts of those seeking to avoid them – people who purchase anti-distraction software like “Freedom” or hide their wi-fi cards. The recognition of the consequences should not imply a wholesale abandonment of the Internet but merely to admit its current design failures. It should direct one’s attention to important and generally unexplored questions. What would an Internet designed around some conception of the good life not rooted in a narrow concern for the speed and efficiency of informational flows look like? What would it take to have one? [1] There are, clearly, other issues with using erotic media as a comparison. Many more socially liberal or libertarian readers may be ideologically predisposed to discount such evidence as obviously motivated by antiquated or conservative forms of moralism, countering that how they explore their sexuality is their own personal choice. (The psychological sciences be damned!) In my mind, mid-twentieth century sexual “liberation” eliminated some damaging and arbitrary taboos but, to too much of an extent, mostly liberated Westerners to have their sexualities increasingly molded by advertisers and media conglomerates. It has not actually amounted to the freeing the internally-developed and independently-derived individual sexuality for the purpose of self-actualization, as various Panglossian historical accounts would have one believe. As long as people on the left retreat to the rhetoric of individual choice, they remain blind to many of the subtle social processes by which sexuality is actually shaped, which are, in many ways, just as coercive as earlier forms of taboo and prohibition. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed