|

If your Facebook wall is like mine, you have seen no shortage of memes trying to convince you that a simple explanation for school shootings exists. One claims that their increase coincides with the decline of proper “discipline” (read: corporeal punishment) of children thirty years ago. Yet all sorts of things have changed over the last several decades, especially since 2011 when the frequency of mass shootings tripled. In any case, Europeans are equally unlikely to strike their children but see no uptick in the likelihood of acts of mass violence—the 2011 attack in Norway notwithstanding. Moreover, assault weapons like the AR-15 have been available for fifty years and a federal assault weapon ban (i.e., “The Brady Bill”) expired back in 2004, long before today’s upswing in shootings. Under the slightest bit of scrutiny, any single-cause explanation begins to unravel.

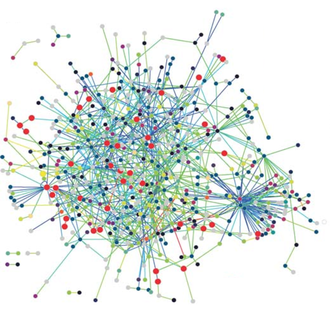

Journalists and other observers often note that the perpetrators of these events were “loners” or socially isolated but do little to no further investigation when it comes time to recommend solutions. It is as if we have begun to accept the existence of such isolated and troubled individuals as if it were natural, as if little could be done to prevent it, as if eliminating civilian weapons or de-secularizing society were less wicked of problems. If there is any mindset my book, Technically Together, tries to eliminate, it is the belief that the social lives offered to us by contemporary networked societies are unalterable—the idea that we have arrived at the best of all possible social worlds. Indeed, it is difficult to square sociologist Keith Hampton’s claim that “because of cellphones and social media, those we depend on are more accessible today than at any point since we lived in small, village-like settlements” with massive increases in the rates of medication use for depression and anxiety, not just the frequency of mass shootings. At the very least, digital technologies—for all their wonders—do less than is needed to remedy feelings of isolation. Such changes, I contend, suggest that something is very wrong with contemporary practices of togetherness. No doubt most of us get by well enough with some mixture of social networks, virtual communities, and perhaps a handful of neighborly and workplace-based connections (if we’re lucky). That said, most goods, social or otherwise, are unequally distributed. Even if sociologists disagree about whether social ties have changed on average, the distribution of connection has and so have the qualitative dimensions of friendship. For every social butterfly who uses online networks to maintain levels of acquaintanceship that would have been impossible in the days of rolodexes and phone conversations, there are those for whom increasing digital mediation has meant a decline in companionship in both numeracy and intimacy. As nice as “lurking” on Facebook or a pleasant comment from a semi-anonymous Reddit compatriot can be, they cannot match a hug. Indeed, self-reported loneliness and expressed difficulties in sustaining close friendships persist among the older generations and young men despite no lack of digital mechanisms for connecting with others. Some sociologists downplay this, as if highlighting the downsides to social networks invariably leads to simplistically blaming them for people’s problems. No doubt Internet-critics like Sherry Turkle overlook many of the complexities of digital-age sociality, but only those socially advantaged by contemporary network technologies benefit from viewing them through rose-colored glasses. Certainly an explanation for mass shootings cannot be reduced to the prevalence of digital technologies, just as it cannot be blamed simply on the ostensible disappearance of God from schools, declines in juvenile corporeal punishment, the mere presence of assault weapons, or any of the other purported causes that proliferate in the media. What Internet technologies do provide, however, is a window into society—insofar as they can exacerbate or make more visible social changes set in motion decades earlier. To try to blame the Internet for social isolation would fail to recognize that it was suburbia that first physically isolated people. It makes the warm intimacy of bodily co-presence hard work; hanging out requires gas money as well as the time and energy to drive to somewhere. Skeptical readers would probably point out that events like mass shootings became prevalent and accelerated well after the suburb-building boom of the mid-20th century. That objection is easy to counter: social lag. The first suburban dwellers brought with them communal practices learned in small towns or tight-knit urban neighborhoods, and their children maintained some of them. 30 Rock’s Jack Donaghy lamented that 1st generation immigrants work their fingers to the bone, the 2nd goes to college, and the 3rd snowboards and takes improv classes. A similar generational slide could be said about community in suburbia: The 1st generation bowls together; the 2nd organizes neighborhood watch; the 3rd waits with their kids in the car until the school bus arrives. Even while considering all that the physical makeup of our cities does to stifle community life, it would be a mistake not to recognize that there is something unique about many of our Internet activities that make them far more conducive to feelings of loneliness than other media—even if they do connect us with friends. Consider how one woman in the BBC documentary, The Age of Loneliness, laments that social media makes her feel even lonelier, because she cannot help but compare her own life to the “highlights reels” posted by acquaintances. Others use the Internet to avoid the painful awkwardness and risk of in-person interactions, getting stuck in a downward spiral of solitude. These features combine with a third to help give birth to mass shooters: The “long tail” of the Internet provides websites that concentrate and amplify pathological tendencies. Forums that encourage and help people with eating disorders continue damaging behaviors are as common as racist, violence-promoting websites, many of which had been frequented by recent mass shooters. While it is the suburbs that physically isolate people and make physical friendships practically difficult, online social networks too easily exacerbate and highlight that isolation. My point, however, is not to call for dismantling the Internet—though I think it could use a massive redesign. Such a call would be as simple-minded as believing that just eliminating AR-15s or making kids read the Bible in school would prevent acts of mass violence. Appeals to improving mental health services or calls to arm teachers or place military veterans at schools are equally misguided. These are all band-aid solutions that fail to ask about the underlying causes. What we need most is not more guns, God, scrutinization of the mentally ill, or even necessarily gun bans, but a sober evaluation of our social world: Why does it not provide adequate levels of loving togetherness and belonging to nearly everyone? How could it? To some this might sound like a call to coddle potential murderers. Yet, given that people’s genetics do not fully explain their personalities, societies have to reckon with the fact that mass shooters are not born ready-made monsters but become that way. It is difficult not to see parallels between many young men today and the “lost generation” that was so liable to fall prey to fascism in the early 20th century. The growth of, mainly white, young, and male, mass shooters cannot be totally unrelated to the increase in, mainly white, young, and male, acolytes of prophets like Jordan Peterson, who extol the virtues of traditional notions of male power. Absent work toward ameliorating the “crisis of connection” that many face men currently face, we should be unsurprised if some of them continue to try to replace a lost sense of belonging with violent power fantasies.

Although it seems clears that mid-20th century predictions of the demise of community have yet to come to pass—most people continue to socially connect with others—many observers are too quick to declare that all is well. Indeed, in my recent book, I critique the tendency by some contemporary sociologists to write as if people today have never had it better when it comes to social togetherness, as if we have reached a state of communal perfection. The way that citizens do community in contemporary technological societies has been breathlessly described as a new “revolutionary social operating system” that recreates the front porch of previous generations within our digital devices. There is quite a lot to say regarding how such pronouncements fail to give recognition to the qualitative changes to social life in the digital age, changes that impact how meaningful and satisfying people find it to be. Here I will just focus on one particular way in which contemporary community life is relatively thinner than what has existed at other times and places.

After she was raped in 2013, Gina Tron’s social networks were anything but revolutionary. In addition to the trauma of the act itself, she suffered numerous indignities in the process of trying to work within the contemporary justice system to bring charges against her attacker. During such trying times, at a moment when one would most need the loving support of friends, her social network abandoned her. Friends shunned her because they were afraid of having to deal with emotional outbursts, because they worried that just hearing about the experience would be traumatic, or because they felt that they would not be able to moan melodramatically about their more mundane complaints in the presence of someone with a genuine problem. Within the logic of networked individualism, that revolutionary social operating system extoled by some contemporary sociologists, such behavior is unsurprising. Social networks are defined not so much by commitment but by mutually advantageous social exchanges. Social atoms connect to individually trade something of value rather than because they share a common world or devotion to a common future. For members of Tron’s social network, the costs of connecting after her rape seemed to exceed the benefits; socializing in the aftermath of the event would force them to give more support than they themselves would receive. Even the institutions that had previously centered community life—namely churches—now often function similarly to weak social networks. Many evangelical churches seem more like weekly sporting events than neighborhood centers, boasting membership rolls in the thousands and putting on elaborate multimedia spectacles in gargantuan halls that often rival contemporary pop music acts. No doubt social networks do form through such places, providing smaller scale forms of togetherness and personal support in times of need. Yet there are often firm limits to the degree of support such churches will give, limits that many people would find horrifying. A large number of evangelical megachurches have their roots in and continue to preach prosperity theology. In this theological system, God is believed to reliably provide security and prosperity to those who are faithful and pious. A byproduct of such a view is that leaders of many, if not most, megachurches find it relatively unproblematic to personally enrich themselves with the offerings given by (often relatively impoverished) attendees, purchasing million dollar homes and expensive automobiles. Prosperity theology gives megachurch pastors a language through which they can frame such actions as anything but unethical or theologically contradictory, but rather merely a reflection and reinforcement of their own godliness. The worst outcome of prosperity theology comes out of logically deducing its converse: If piety brings prosperity, then hardship must be the result of sin and faithlessness. Indeed, as Kate Bowler describes, one megachurch asked a long-attending member stricken with cancer to stop coming to service. The fact that his cancer persisted, despite his membership, was taken as sign of some harmful impropriety; his presence, as a result, was viewed as posing a transcendental risk to the rest of the membership. It appears that, within prosperity theology, community is to be withdrawn from members in their moments of greatest need. However, many contemporary citizens have largely abandoned traditional religious institutions, preferring instead to worship at the altar of physical performance. CrossFit is especially noteworthy for both the zeal of its adherents and the viciousness of the charges launched by critics, who frequently describe the fitness movement as “cultlike.” Although such claims can seem somewhat exaggerated, there is some kernel of truth to them. Julie Beck, for instance, has recently noted the extreme evangelical enthusiasm of many CrossFitters. While there is nothing problematic about developing social community via physical recreation per se—indeed, athletic clubs and bowling leagues served that purpose in the past—what caught my eye about CrossFit was how easy it was to be pushed out of the community. There is an element of exclusivity to it. Adherents like to point to disabled members as evidence that CrossFit is ostensibly for everyone. Yet for those who get injured, partly as a result of the fitness movement’s narrow emphasis on “beat the clock” weightlifting routines at the expense of careful attention to form, frequently find themselves being assigned sole responsibility for damaging their bodies. Although the environment encourages—even deifies—the pushing of limits, individual members are themselves blamed if they go too far. In any case, those suffering an injury are essentially exiled, at least temporarily; there are no “social” memberships to CrossFit: You are either there pushing limits or not there at all. In contrast to Britney Summit-Gil’s argument that community is characterized by the ease by which people can leave, I contend that thick communities are defined by the stickiness of membership. I do not mean that it is necessarily hard to leave them—they are by no means cults—but that membership is not so easily revoked, and especially not during times of need. No doubt there are advantages to thinly communal social networks. People use them to advance their career, fundraise for important causes, and build open source software. Yet we should be wary of their underlying logic of limited commitment, of limited liability, becoming the model for community writ large. If social networks are indeed revolutionary, then we should carefully examine their politics: Do they really provide us with the “liberation” we seek or just new forms of hardship? Have new masters simply taken the place of the old ones? Those are questions citizens cannot begin to intelligently consider if they are too absorbed with marveling over new technical wonders, too busy standing in awe of the strength of weak ties. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed