|

Are Americans losing their grip on reality? It is difficult not to think so in light of the spread of QANON conspiracy theories, which posit that a deep-state ring of Satanic pedophiles is plotting against President Trump. A recent poll found that some 56% of Republican voters believe that at least some of the QANON conspiracy theory is true. But conspiratorial thinking has been on the rise for some time. One 2017 Atlantic article claimed that America had “lost its mind” in its growing acceptance of post-truth. Robert Harris has more recently argued that the world had moved into an “age of irrationality.” Legitimate politics is threatened by a rising tide of unreasonableness, or so we are told. But the urge to divide people in rational and irrational is the real threat to democracy. And the antidote is more inclusion, more democracy—no matter how outrageous the things our fellow citizens seem willing to believe.

Despite recent panic over the apparent upswing in political conspiracy thinking, salacious rumor and outright falsehoods has been an ever-present feature of politics. Today’s lurid and largely evidence-free theories about left-wing child abuse rings have plenty of historical analogues. Consider tales of Catherine the Great’s equestrian dalliances and claims that Marie Antoinette found lovers in both court servants and within her own family. Absurd stories about political elites seems to have been anything but rare. Some of my older relatives believed in the 1990s that the government was storing weapons and spare body parts underneath Denver International Airport in preparation for a war against common American citizens—and that was well before the Internet was a thing. There seems to be little disagreement that conspiratorial thinking threatens democracy. Allusions to Richard Hofstadter’s classic essay on the “paranoid style of American politics” have become cliché. Hofstadter’s targets included 1950s conservatives that saw Communist treachery around every corner, 1890s populists railing against the growing power of the financial class, and widespread worries about the machinations of the Illuminati. He diagnosed their politics paranoid in light of their shared belief that the world was being persecuted by a vast cabal of morally corrupt elites. Regardless of their specific claims, conspiracy theories’ harms come from their role in “disorienting” the public, leading citizens to have grossly divergent understandings of reality. And widespread conspiratorial thinking drives the delegitimation of traditional democratic institutions like the press and the electoral system. Journalists are seen as pushing “fake news.” The voting booths become “rigged.” Such developments are no doubt concerning, but we should think carefully about how we react to conspiracism. Too often the response is to endlessly lament the apparent end of rational thought and wonder aloud if democracy can survive while being gripped by a form of collective madness. But focusing on citizens' perceived cognitive deficiencies presents its own risks. Historian Ted Steinberg called this the “diagnostic style” of American political discourse, which transforms “opposition to the cultural mainstream into a form of mental illness.” The diagnostic style leads us to view QANONers, and increasingly political opponents in general, as not merely wrong but cognitively broken. They become the anti-vaxxers of politics. While QANON believers certainly seem to be deluding themselves, isn’t the tendency by leftists to blame Trump’s popular support on conservative’s faculty brains and an uneducated or uninformed populace equally delusional? The extent to which such cognitive deficiencies are actually at play is beside the point as far as democracy is concerned. You can’t fix stupid, as the well-worn saying has it. Diagnosing chronic mental lapses actually leaves us very few options for resolving conflicts. Even worse, it prevents an honest effort to understand and respond to the motivations of people with strange beliefs. Calling people idiots will only cause them to dig in further. Responses to the anti-vaxxer movement show as much. Financial penalties and other compulsory measures tend to only anger vaccine hesitant parents, leading them to more often refuse voluntary vaccines and become more committed in their opposition. But it does not take a social scientific study to know this. Who has ever changed their mind in response to the charge of stupidity or ignorance? Dismissing people with conspiratorial views blinds us to something important. While the claims themselves might be far-fetched, people often have legitimate reasons for believing them. African Americans, for instance, disproportionately believe conspiracy theories regarding the origin of HIV, such as that it was man-made in a laboratory or that the cure was being withheld, and are more hesitant of vaccines. But they also rate higher in distrust of medical institutions, often pointing to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and ongoing racial disparities as evidence. And from British sheepfarmers’ suspicion of state nuclear regulators in the aftermath of Chernobyl to mask skeptics’ current jeremiads against the CDC, governmental mistrust has often developed after officials’ overconfident claims about the risks turned out to be inaccurate. What might appear to an “irrational” rejection of the facts is often a rational response to a power structure that feels distant, unresponsive, and untrustworthy. The influence of psychologists has harmed more than it has helped in this regard. Carefully designed studies purport to show that believers in conspiracy theories lack the ability to think analytically or claim that they suffer from obscure cognitive biases like “hypersensitive agency detection.” Recent opinion pieces exaggerate the “illusory truth effect,” a phenomenon discovered in psych labs that repeated exposure to false messages leads to a relatively slight increase in the number subjects rating them as true or plausible. The smallness of this, albeit statistically significant, effect doesn’t stop commentators from presenting social media users as if they were passive dupes, who only need to be told about QANON so many times before they start believing it. Self-appointed champions of rationality have spared no effort to avoid thinking about the deeper explanations for conspiratorial thinking. Banging the drum over losses in rationality will not get us out of our present situation. Underneath our seeming inability to find more productive political pastures is a profound misunderstanding of what makes democracy work. Hand Wringing over “post-truth” or conspiratorial beliefs is founded on the idea that the point of politics is to establish and legislate truths. Once that is your conception of politics, the trouble with democracy starts to look like citizens with dysfunctional brains. When our fellow Americans are recast as cognitively broken, it becomes all too easy to believe that it would be best to exclude or diminish the influence of people who believe outrageous things. Increased gatekeeping within the media or by party elites and scientific experts begins to look really attractive. Some, like philosopher Jason Brennan, go even further. His 2016 book, Against Democracy, contends that the ability to rule should be limited to those capable of discerning and “correctly” reasoning about the facts, while largely sidestepping the question of who decides what the right facts are and how to know when we are correctly reasoning about them. But it is misguided to think that making our democracy only more elitist will throttle the wildfire spread of conspiratorial thinking. If anything, doing so will only temporarily contain populist ferment, letting pressure build until it eventually explodes or (if we are lucky) economic growth leads it to fizzle out. Political gatekeeping, by mistaking supposed deficits in truth and rationality for the source of democratic discord, fails to address the underlying cause of our political dysfunction: the lack of trust. Signs of our political system’s declining legitimacy are not difficult to find. A staggering 71 percent of the Americans believe that elected officials don’t care about the average citizen or what they think. Trust in our government has never been lower, with only 17 percent of citizens expressing confidence about Washington most or all the time. By diagnosing rather than understanding, we cannot see that conspiratorial thinking is the symptom rather than the disease. The spread of bizarre theories about COVID-19 being a “planned” epidemic or child-abuse rings is a response to real feelings of helplessness, isolation, and mistrust as numerous natural and manmade disasters unfold before our eyes—epochal crises that governments seem increasingly incapable of getting a handle on. Many of Hofstadter’s listed examples of conspiratorial thought came during similar moments: at the height of the Red Scare and Cold War nuclear brinkmanship, during the 1890s depression, or in the midst of pre-Civil War political fracturing. Conspiracy theories offer a simplified world of bad guys and heroes. A battle between good and evil is a more satisfying answer than the banality of ineffectual government and flawed electoral systems when one is facing wicked problems. Perhaps social media adds fuel to the fire, accelerating the spread of outlandish proposals about what ails the nation. But it does so not because it short-circuits our neural pathways to crash our brains’ rational thinking modules. Conspiracy theories are passed by word of mouth (or Facebook likes) by people we already trust. It is no surprise that they gain traction in a world where satisfying solutions to our chronic, festering crises are hard to find, and where most citizens are neither afforded a legible glimpse into the workings of the vast political machinery that determines much of their lives nor the chance to actually substantially influence it. Will we be able to reverse course before it is too late? If mistrust and unresponsiveness is the cause, the cure should be the effort to reacquaint Americans with the exercise of democracy on a broad-scale. Hofstadter himself noted that, because the political process generally affords more extreme sects little influence, public decisions only seemed to confirm conspiracy theorists’ belief that they are a persecuted minority. The urge to completely exclude “irrational” movements forgets that finding ways to partially accommodate their demands is often the more effective strategy. Allowing for conscientious objections to vaccination effectively ended the anti-vax movement in early 20th century Britain. Just as interpersonal conflicts are more easily resolved by acknowledging and responding to people’s feelings, our seemingly intractable political divides will only become productive by allowing opponents to have some influence on policy. That is not to say that we should give into all their demands. Rather it is only that we need to find small but important ways for them to feel heard and responded to, with policies that do not place unreasonable burdens on the rest of us. While some might pooh-pooh this suggestion, pointing to conspiratorial thinking as evidence of how ill-suited Americans are for any degree of political influence, this gets the relationship backwards. Wisdom isn’t a prerequisite to practicing democracy, but an outcome of it. If our political opponents are to become more reasonable it will only be by being afforded more opportunities to sit down at the table with us to wrestle with just how complex our mutually shared problems are. They aren’t going anywhere, so we might as well learn how to coexist. As a scholar concerned about the value of democracy within contemporary societies, especially with respect to the challenges presented by increasingly complex (and hence risky) technoscience, a good check for my views is to read arguments by critics of democracy. I had hoped Jason Brennan's Against Democracy would force me to reconsider some of the assumptions that I had made about democracy's value and perhaps even modify my position. Hoped.

Having read through a few chapters, I am already disappointed and unsure if the rest of the book is worth the my time. Brennan's main assertion is that because some evidence shows that participation in democratic politics has a corrupting influence--that is, participants are not necessarily well informed and often end becoming more polarized and biased in the process--we would be better off limiting decision making power to those who have proven themselves sufficiently competent and rational, to epistocracy. Never mind the absurdity of the idea that a process for judging those qualities in potential voters could ever be made in an apolitical, unbiased, or just way, Brennan does not even begin with a charitable or nuanced understanding of what democracy is or could be. One early example that exposes the simplicity of Brennan's understanding of democracy--and perhaps even the circularity of his argument--is a thought experiment about child molestation. Brennan asks the reader to consider a society that has deeply deliberated the merits of adults raping children and subjected the decision to a majority vote, with the yeas winning. Brennan claims that because the decision was made in line with proper democratic procedures, advocates of a proceduralist view of democracy must see it as a just outcome. Due to the clear absurdity and injustice of this result, we must therefore reject the view that democratic procedures (e.g., voting, deliberation) themselves are inherently just. What makes this thought experiment so specious is that Brennan assumes that one relatively simplistic version of a proceduralist, deliberative democracy can represent the whole. Ever worse, his assumed model of deliberative democracy--ostensibly not too far from what already exists in most contemporary nations--is already questionably democratic. Not only is majoritarian decision-making and procedural democracy far from equivalent, but Brennan makes no mention of whether or not children themselves were participants in either the deliberative process or the vote, or even would have a representative say through some other mechanism. Hence, in this example Brennan actually ends up showing the deficits of a kind of epistocracy rather than democracy, insofar as the ostensibly more competent and rationally thinking adults are deliberating and voting for children. That is, political decisions about children already get made by epistocrats (i.e., adults) rather than democratically (understood as people having influence in deciding the rules by which they will be governed for the issues they have a stake in). Moreover, any defender of the value of democratic procedures would likely counter that a well functioning democracy would contain processes to amplify or protect the say of less empowered minority groups, whether through proportional representation or mechanisms to slow down policy or to force majority alliances to make concessions or compromises. It is entirely unsurprising that democratic procedures look bad when one's stand-in for democracy is winner-take-all, simple majoritarian decision-making. His attack on democratic deliberations is equally short-sighted. Criticizing, quite rightly, that many scholars defend deliberative democracy with purely theoretical arguments, while much of the empirical evidence shows that many average people dislike deliberation and are often very bad at it, Brennan concludes that, absent promising research on how to improve the situation, there is no logical reason to defend deliberative democracy. This is where Brennan's narrow disciplinary background as a political theorist biases his viewpoint. It is not at all surprising to a social scientist that average people would fail to deliberate well nor like it when the near entirety of contemporary societies fails to prepare them for democracy. Most adults have spent 18 years or more in schools and up to several decades in workplaces that do not function as democracies but rather are authoritarian, centrally planned institutions. Empirical research on deliberation has merely uncovered the obvious: People with little practice with deliberative interactions are bad at them. Imagine if an experiment put assembly line workers in charge of managing General Motors, then justified the current hierarchical makeup of corporate firms by pointing to the resulting non-ideal outcomes. I see no reason why Brennan's reasoning about deliberative democracy is any less absurd. Finally, Brennan's argument rests on a principle of competence--and concurrently the claim that citizens have a right to governments that meet that principle. He borrows the principle from medical ethics, namely that a patient is competent if they are aware of the relevant facts, can understand them, appreciate their relevance, and can reason about them appropriately. Brennan immediately avoids the obvious objections about how any of the judgements about relevance and appropriateness could be made in non-political ways to merely claim that the principle is non-objectionable in the abstract. Certainly for the simplified thought examples that he provides of plumber's unclogging pipes and doctors treating patients with routine conditions the validity of the principle of competence is clear. However, for the most contentious issues we face: climate change, gun control, genetically modified organisms, etc., the facts themselves and the reliability of experts are themselves in dispute. What political system would best resolve such a dispute? Obviously it could not be a epistocracy, given that the relevance and appropriateness of the "relevant" expertise itself is the issue to be decided. Perhaps Brennan's suggestions have some merit, but absent a non-superficial understanding of the relationship between science and politics the foundation of his positive case for epistocracy is shaky at best. His oft repeated assertion that epistocracy would likely produce more desirable decisions is highly speculative. I plan on continuing to examine Brennan's arguments regarding democracy, but I find it ironic that his argument against average citizens--that they suffer too much from various cognitive maladies to reason well about public issues--applies equally to Brennan. Indeed, the hubris of most experts is deeply rooted in their unfounded belief that a little learning has freed them from the mental limitations that infect the less educated. In reality, Brennan is a partisan like anyone else, not a sagely academic doling out objective advice. Whether one turns to epistocratic ideas in light of the limitations of contemporary democracies or advocate for ensuring the right preconditions for democracies to function better comes back to one's values and political commitments. So far it seems that Brennan's book demonstrates his own political biases as much as it exposes the ostensibly insurmountable problems for democracy. 10/6/2017 Why the Way We Talk About Politics Will Ensure that Mass Shootings Keep HappeningRead Now

After news broke of the Las Vegas shooting, which claimed some 59 lives, professional and lay observers did not hesitate in trotting out the same rhetoric that Americans have heard time and time again. Those horrified by the events demanded that something be done; indeed, the frequency and scale of these events should be horrifying. Conservatives, in response, emphasized evidence for what they see as the futility of gun control legislation. Yet it is not so much gun control itself that seems futile but rather our collective efforts to accomplish almost any policy change. The Onion satirized America's firearm predicament with the same headline used after numerous other shootings: “‘No Way to Prevent This,’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens.” Why is it that we Americans seem so helpless to effect change with regard to mass shootings? What explains our inability to collectively act to combat these events?

Political change is, almost invariably, slow and incremental. Although the American political system is, by design, uniquely conservative and biased toward maintaining the status quo, that is not the only reason why rapid change rarely occurs. Democratic politics is often characterized as being composed by a variety of partisan political groups, all vying with one another to get their preferred outcome on any given policy area: that is, as pluralistic. When these different partisan groups are relatively equal and numerous, change is likely to be incremental because of substantial disagreements between these groups and the fact that each only has a partial hold on power. Relative equality among them means that any policy must be a product of compromise and concession—consensus is rarely possible. Advocates of environmental protection, for instance, could not expect to convince governments to immediately dismantle of coal-fired power plants, though they might be able to get taxes, fines, or subsidies adjusted to discourage them; the opposition of industry would prevent radical change. Ideally, the disagreements and mutual adjustments between partisans would lead to a more intelligent outcome than if, say, a benevolent dictator unilaterally decided. While incremental policy change would be expected even in an ideal world of relatively equal partisan groups, things can move even slower when one or more partisan groups are disproportionately powerful. This helps explain why gun control policy—and, indeed, environmental protections, and a whole host of other potentially promising changes—more often stagnates than advances. Businesses occupy a relatively privileged position compared to other groups. While the CEO of Exxon can expect the president’s ear whenever a new energy bill is being passed, average citizens—and even heads of large environmental groups—rarely get the same treatment. In short, when business talks, governments listen. Unsurprisingly the voice of the NRA, which is in essence a lobby group for the firearm industry, sounds much louder to politicians than anyone else’s—something that is clear from the insensitivity of congressional activity to widespread support for strengthening gun control policy. But there is more to it that just that. I am not the first person to point out that the strength of the gun lobby stymies change. Being overly focused the disproportionate power wielded by some in the gun violence debate, we miss the more subtle ways in which democratic political pluralism is itself in decline. Another contributing factor to the slowness of gun policy change is the way Americans talk about issues like gun violence. Most news stories, op-eds, and tweets are laced with references to studies and a plethora of national and international statistics. Those arguing about what should be done about gun violence act as if the main barrier to change has been that not enough people have been informed of the right facts. What is worse is that most participants seem already totally convinced of the rightness of their own version or interpretation of those facts: e.g., employing post-Port Arthur Australian policy in the US will reduce deaths or restrictive gun laws will lead to rises in urban homicides. Similar to two warring nations both believing that they have God uniquely on their side, both sides of the gun control debate lay claim to being on the right side of the facts, if not rationality writ large. The problem with such framings (besides the fact that no one actually knows what the outcome would be until a policy is tried out) is that anyone who disagrees must be ignorant, an idiot, or both. That is, exclusively fact-based rhetoric—the scientizing of politics—denies pluralism. Any disagreement is painted as illegitimate, if not heretical. Such as view leads to a fanatical form of politics: There is the side with “the facts” and the side that only needs informed or defeated, not listened to. If “the facts” have already pre-determined the outcome of policy change, then there is no rational reason for compromise or concession, one is simply harming one’s own position (and entertaining nonsense). If gun control policy is to proceed more pluralistically, then it would seem that rhetorical appeals to the facts would need dispensed with—or at least modified. Given that the uncompromising fanaticism of some of those involved seems rooted in an unwavering certainty regarding the relevant facts, emphasizing uncertainty would likely be a promising avenue. In fact, psychological studies find that asking people to face the complexity of public issues and recognize the limits of their own knowledge leads to less fanatical political positions. Proceeding with a conscious acknowledgement of uncertainty would have the additional benefit of encouraging smarter policy. Guided by an overinflated trust that a few limited studies can predict outcomes in exceedingly complex and unpredictable social systems, policy makers tend to institute rule changes or laws with no explicit role for learning. Despite that even scientific theories are only tentatively true, ready to be turned over by evermore discerning experimental tests or shift in paradigm, participants in the debate act as if events in Australia or Chicago have established eternal truths about gun control. As a result, seldom is it considered that new policies could be tested gradually, background check and registration requirements that become more stringent over time or regional rollouts, with an explicit emphasis on monitoring for effectiveness and unintended consequences—especially consequences for the already marginalized. How Americans debate issues like gun control would be improved in still other ways if the narrative of “the facts” were not so dominant in people’s speech. It would allow greater consideration of values, feelings, and experiences. For instance, gun rights advocates are right to note that semiautomatic “assault” weapons are responsible for a minority of gun deaths, but their narrow focus on that statistical fact prevents them from recognizing that it is not their “objective” danger that motivates their opponents but their political riskiness. The assault rifle, due to its use in horrific mass shootings, has come to symbolize American gun violence writ large. For gun control advocates it is the antithesis of conservatives’ iconography of the flag: It represents everything that is rotten about American culture. No doubt reframing the debate in that way would not guarantee more productive deliberation, but it would at least enable political opponents some means of beginning to understand each others' position. Even if I am at least partly correct in diagnosing what ails American political discourse, there remains the pesky problem of how to treat it. Allusions to “the facts,” attempts to leverage rhetorical appeals to science for political advantage, have come to dominant political discourse over the course of decades—and without anyone consciously intending or dictating it. How to effect movement in the opposite direction? Unfortunately, while some social scientists study these kinds of cultural shifts as they occur throughout history, practically none of them research how beneficial cultural changes could be generated in the present. Hence, perhaps the first change citizens could advocate for would be more publicly responsive and relevant social research. Faced with an increasingly pathological political process and evermore dire consequences from epochal problems, social scientists can no longer afford to be so aloof; they cannot afford to simply observe and analyze society while real harms and injustices continue unabated. Certainly there are things to like about the March for Science. As you are likely aware, scientists and engineers have a reputation for being politically aloof. I, for one, am glad to see events like it, which run contrary to that stereotype.

The March for Science website describes the event as a nonpartisan call for politicians to recognize that science upholds the public good: in other words, science matters. I want to push those of you reading this post to critically examine this slogan—to treat it as you would any truth claim. On face value, there seems to be little to disagree with: of course science should matter. Good luck solving any 21st century challenge without it. Hence, I think it is more interesting to ask, “Which science should matter? And how much?” Some of you may find this to be a provocative turn of phrase, because it applies to science a standard definition of politics: that is, politics as any answer to the question “What gets what, when, and how?” This is a provocative question because many people, including many scientists and engineers, tend to believe that politics is everything science is not and vice-versa, which in turn supports the idea that advocating for science can be a non-partisan activity, that it can be an apolitical social movement. To say today that science should matter, but little more than that, could be construed to imply that we ought to continue with science as we had prior to recent electoral results. Such an implication would appear to be rooted in the presumption that science was previously nonpartisan and only recently tainted by political agendas. Is that a wise presumption? Certainly the current administration’s attempts to excise climate science from NASA and muzzle the EPA can be recognized as political. But what about the historical relationship between science and military applications, running all the way from Archimedes to the United States today—where some $77 billion gets spent on military R&D annually compared to $69 billion on nondefense research? What about the fact that a paltry portion of public research money is dedicated to developing non-toxic alternatives to the suspected and confirmed carcinogens and endocrine disruptors found inside most consumer products, toxins which invariably end up in the environment and, thus, in human bodies. Compare that to the billions that always seems await every new overhyped and highly risky area of innovation: nano-tech, syn-bio, and so on. I don’t assume that you will agree with my own valuation of the relative worthiness of these different areas of science, but I hope you can join me in recognizing that such discrepancies in funding and attention do not exist because one area is more scientific than the others. If historians who can study our time period even exist in 100 years, they will likely find our belief that science is nonpartisan as perplexing to say the least. How could a sophisticated society believe in such an idea when it is obvious that some areas of science matter more than others and some science gets ignored? How could they sustain such a belief when the advantages of military R&D and the harms of toxic consumer products clearly accrue more strongly to some people than others? Some clearly win because of this arrangement, while others lose. I don’t say this to denigrate science but to denigrate one of the myths that undergirds the political aloofness that is so common among scientists and engineers. My message to you is that you’re already and always partisan. That is a reality that will not disappear simply by not believing in it. Accepting this message, I would argue, is not as destructive as one might believe at first. Rather, I think it is freeing: it enables one to act more wisely in the world, rather than be misguided by a “flat Earth theory” of politics. There is no abyss to fall into wherein one ceases to be scientific, in turn becoming political. One is already and always both. Therefore, it is not a question of whether science and engineering is partisan or not, but a question of what kind of partisans scientists and engineers should be: self-conscious ones or ones asleep at the wheel? What kind of technoscientific world will you be a partisan for? Which science should matter? And how much? It is an understatement to say that the case of Anna Stubblefield is simply controversial. Opinions of the former Rutgers professor, who was recently sentenced to some 10 odd years in prison for the charge of sexually assaulting a disabled man, are highly polarized. When reading comments on recent news stories on the case, one finds not only people who find her absolutely abhorrent but also people who empathize or support her side. No doubt there are important issues to consider regarding the rights of disabled persons, professional ethics, racism, and the nature of consent. However, I want to focus on how the framing of the case as a battle between science and pseudoscience prevents us from sensibly dealing with the politics underlying the issue. The case is strongly shaped by a broader dispute over of the scientific status of “facilitated communication” (FC), a technique claimed by its advocates to allow previously voiceless people with cerebral palsy or autism to speak. As its name suggests, a facilitator helps guide the disabled person’s hand to a keyboard. In the most favorable reading of the practice, the facilitator simply balances out the muscle contractions and lessens the physical barriers to typing. Some see the practice, however, as more than mere assistance: they claim that the facilitator is the one really doing the typing, either consciously or unconsciously. In the former case, FC is a wonderful gift for those suffering from disabilities and their families. In latter reading, facilitators are charlatans, utilizing a pseudoscientific technique to deceive people. "Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations." This latter view seems to have won out in the case of Anna Stubblefield, who claims that DJ--a man with profound physical and suspected mental disabilities—consented to have sex with her via FC. The court rules that FC did not meet the state standards for science. Hence, Stubblefield was unable to mount a much of a defense vis-à-vis FC.

Most people fail to grasp, however, exactly how hard it is to distinguish science and pseudoscience—despite whatever popularizers like Neil DeGrasse Tyson or Bill Nye seem to claim. Science does not simply produce unquestionable facts, rather it is a skilled practice; its capacity to prove truth is always partial, seen far better in hindsight than in the moment. As science and technology studies scholars well illustrate, experiments are incredibly complex—only becoming more so when their results are controversial. The fact that many scientific activities are heavily dependent on the skill of the scientist is on the one hand obvious, but nevertheless eludes most people. Mid-20th century experiments attempting to transfer memories (e.g., fear of the dark, how to run a maze) between planarian worms or mice exemplify this facet of science. Skeptical and supportive scientists went back and forth incessantly over methodological disagreements in trying to determine whether the observed effects were “real,” eventually considering more than 70 separate variables as possible influences on the outcome of memory transfer experiments. Even though some skeptical scientists derided skill-based variables as a so-called “golden hands” argument, there are plenty of areas of science where an experimentalist’s skill makes or breaks an experiment. Biologists, in particular, frequently lament the difficulty of keeping an RNA sample from breaking down or find themselves developing fairly eccentric protocols for getting “good” results out of a Western Blot or bioassay experiment. What some will view as ad-hoc “golden hands” excuses are often simply facets of doing a complex and highly sensitive procedure. A similar dispute over the role of the skill of the practitioner makes FC controversial. After rosy beginnings, skeptical scientists produced results that cast doubt on the technique. Experiments involved the attempt to duplicate text generated with the help of a disabled person’s usual facilitator with a “naïve” facilitator or the asking of questions to which the facilitator wouldn’t know the answer. Indeed, just such an experiment was conducted with DJ, for which both sides claimed victory (Jeff McMahan and Peter Singer, for instance, argue that DJ is more cognitively able than the prosecution would have one believe). As has been the case for other controversial scientific phenomenon, FC only becomes more complex the more deeply one looks into it. Advocates of the method raise their own doubts about studies claiming to disprove the technique’s effectiveness, contending that facilitation requires skills and sensitivities unique to the person being facilitated and that the stressfulness of the testing environment skews the results in the favor of skeptics. There is enough uncertainty surrounding the abilities of those with autism or cerebral palsy to make reasonable arguments either way. Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations. Again, my point is not to try to argue one way or another for FC but to merely point out that the phenomenon under consideration is immensely complex; we simplify it only at our peril. Indeed, the history of science and technology provides plenty of evidence suggesting that we are better off acknowledging that even today’s best science is unlikely to provide sure answers to a controversial debate. Advocates of nuclear energy, for instance, once claimed that their science proved that an accident was a near impossibility, happening perhaps once in ten thousand years. Similarly, some petroleum geology experts have claimed that it is physically impossible for fracking to introduce natural gas and other contaminants to water supplies: there is simply too much rock in between. Yet, an EPA scientist has recently produced fairly persuasive evidence to the contrary. “Settled science” rhetoric has mainly served to shut down inquiry, and the discovery of contrary findings in ensuing decades only adds support to the view that reaching something like scientific certainty is a long and difficult struggle. As a result, scientific controversies are often as much settled politically as scientifically: they are as much battles of rhetoric as facts. Rather than pretend that absolute certitude were possible, what if we proceeded with controversial practices like FC guided by the presumption that we might be wrong about it? What if we assumed that it was possible the method could work—perhaps for a very small percentage of autistics and those born with severe cerebral palsy--but that we are challenged in our ability to know for whom it worked? Moreover, self-deception—like many believe Anna Stubblefield fell prey to—remains a pervasive risk. The situation changes dramatically. Rather than commit oneself to idea that something is either pure truth or complete pseudoscience, the issue can be framed in terms of risk: given that we may be wrong, who might suffer which benefits and harms? How many cases of sham communication via FC balances out the possibility of a non-communicative person losing their voice? In other words, do we prefer false positives or false negatives? Such a perspective challenges people to think more deeply about what matters with respect to FC. Surely the prospect of disabled people being abused or killed because of communication that originates more with the facilitator than the person being facilitated is horrifying. Yet, on the other hand, Daniel Engeber describes meeting families who feel like FC has been a godsend. Even in the scenario in which FC only provides a comforting delusion, is anyone being harmed? A philosophy professor I once knew remarked that he’d take a good placebo over nothing at all any day of the week. On what grounds do we have to deprive people of controversial (even potentially fictitious) treatment if it is not too harmful and potentially increases the well-being of at least some of the people involved? I don’t have an answer to these questions, but I do know that we cannot begin to debate them if we hide behind a simplistic partitioning of all knowledge into either science or pseudoscience, pretending that such designations can do our politics for us When reading some observer's diagnoses of what ails the United States, one can get the impression that Americans are living in an unprecedented age of public scientific ignorance. There is reason, however, to wonder if people today are really any more ignorant of facts like water boiling at lower temperatures at higher altitudes or if any more people believe in astrology than in the past. According to some studies, Americans have never been more scientifically literate. Nevertheless, there is no shortage of hand-wringing about the remaining degree of public scientific illiteracy and what it might mean for the future of the United States and American democracy. Indeed, scientific illiteracy is targeted as the cause of the anti-vaccination movement as well as opposition to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and nuclear power. However, I think such arguments misunderstand the issue. If America has a problem with regard to science, it is not due to a dearth of scientific literacy but a decline in science's public legitimacy.

The thinking underlying worries about widespread scientific illiteracy is rooted in what is called the “deficit model.” In the deficit model, the cause of the discrepancy between the beliefs of scientists and those are the public is, in the words of Dietram Scheufele and Matthew Nisbet, a “failure in transmission.” That is, it is believed that negligence of the media to dutifully report the “objective” facts or the inability of an irrational public to correctly receive those facts prevents the public from having the “right” beliefs regarding issues like science funding or the desirability of technologies like genetically modified organisms. Indeed, a blogger for Scientific American blames the opposition of liberals to nuclear power on “ignorance” and “bad psychological connections.” It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to say that the deficit model depicts anyone who is not a technological enthusiast as uninformed, if not idiotic. Regardless of whether or not the facts regarding these issues are actually “objective” or totally certain (both sides dispute the validity of each other’s arguments on scientific grounds), it remains odd that deficit model commentators view the discrepancy between scientists’ and the public’s views on GMOs and other issues as a problem for democracy. Certainly they are correct that it is preferable to have a populace that can think critically and suffers from few cognitive impairments to inquiry when it comes to wise public decision making. Yet, the idea that, when properly “informed” of the relevant facts, scientifically literate citizens would immediately agree with experts is profoundly undemocratic: It belittles and erases all the relevant disagreements about values and rights. Such a view ignores, for instance, the fact that the dispute over GMO labeling has as much to do with ideas about citizens’ right to know and desire for transparency as the putative safety of GMOs. By acting as if such concerns do not matter – that only the outcome of recent safety studies do – the people sharing those concerns are deprived of a voice. The deficit model inexorably excludes those not working within a scientistic framework from democratic decision making. Given the deficit model’s democratic deficits as well as the lack of any evidence that scientific illiteracy is actually increasing, advocates of GMOs and other potentially risky instances of technoscience ought to look elsewhere for the sources of public scientific controversy. If anything has changed in the last decades it is that science and technology have less legitimacy. Indeed, science writers could better grasp this point by reading one of their own. Former Discover writer Robert Pool notes that the point of legal and regulatory challenges to new technoscience is not simply to render it safer but also more acceptable to citizens. Whether or not citizens accept a new technology depends upon the level of trust they have of technical experts (and the firms they work for). Opposition to GMOs, for instance, is partly rooted in the belief that private firms such as Monsanto cannot be trusted to adequately test their products and that the FDA and EPA are too toothless (or captured by industry interests) to hold such companies to a high enough standard. Technoscientists and cheerleading science writers are probably oblivious to the workings and requirements for earning public trust because they are usually biased to seeing new technologies as already (if not inherently) legitimate. Those deriding the public for failing to recognize the supposedly objective desirability of potentially risky technology, moreover, have fatally misunderstood the relationship between expertise, knowledge, and legitimacy. It is unreasonable to expect members of the public to somehow find the time (or perhaps even the interest) to learn about the nuances of genetic transmission or nuclear safety systems. Such expectations place a unique and unfair burden on lay citizens. Many technical experts, for instance, might be found to be equally ignorant of elementary distinctions in the social sciences or philosophy. Yet, few seem to consider such illiteracies to be equally worrisome barriers to a well-functioning democracy. In any case, as political scientists Joseph Morone and Edward Woodhouse argue, the position of the public is not to evaluate complex or arcane technoscientific problems directly but to decide which experts to trust to do so. Citizens, according to Morone and Woodhouse, were quite reasonable to turn against nuclear power when overoptimistic safety estimates were proven wrong by a series of public blunders, including accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, as well as increasing levels of disagreement among experts. Citizens’ lack of understanding of nuclear physics was beside the point: The technology was oversold and overhyped. The public now had good grounds to believe that experts were not approaching nuclear energy or their risk assessments responsibly. Contrary to the assumptions of deficit modelers, legitimacy is not earned simply through technical expertise but via sociopolitical demonstrations of trustworthiness. If technoscientific experts were to really care about democracy, they would think more deeply about how they could better earn legitimacy in the eyes of the public. At the very least, research in science and technology studies provides some guidance on how they ought not to proceed. For example, after post-Chernobyl accident radiation rained down on parts of Cumbria, England, scientists quickly moved in to study the effects as well as ensure that irradiated livestock did not get moved out of the area. Their behavior quickly earned them the ire of local farmers. Scientists not only ignored the relevant expertise that farmers had regarding the problem but also made bold pronouncements of fact that were later found to be false, including the claim that the nearby Sellafield nuclear processing plant had nothing to do with local radiation levels. The certainty with which scientists made their uncertain claims as well as their unwillingness to respond to criticism by non-scientists led farmers to distrust them. The scientists lost legitimacy as local citizens came to believe that they were sent there by the national government to stifle inquiry into what was going on rather than learn the facts of the matter. Far too many technoscientists (or at least their associated cheerleaders in popular media) seem content to repeat the mistakes of these Cumbrian radiation scientists. “Take your concerns elsewhere. The experts are talking,” they seem to say when non-experts raise concerns, “Come back when you’ve got a science degree.” Ironically (and tragically), experts’ embrace of deficit model understandings of public scientific controversies undermines the very mechanisms by which legitimacy is established. If the problem is really a deficit of public trust, diminishing the transparency of decisions and eliminating possibilities for citizen participation is self-defeating. Anything looking like a constructive and democratic resolution to controversies like GMOs, fracking, or nuclear energy is only likely to happen if experts engage with and seek to understand popular opposition. Only then can they begin to incrementally reestablish trust. Insofar as far too many scientists and other experts believe they deserve public legitimacy simply by their credentials – and some even denigrate lay citizens as ignorant rubes – public scientific controversies are likely to continue to be polarized and pathological. The belief that science and religion (and science and politics for that matter) are exact opposites is one of the most tenacious and misguided viewpoints held by Americans today, one that is unfortunately reinforced by many science journalists. Science is not at all faith-based, claims Forbes contributor Ethan Siegel in his rebuke of Matt Emerson’s suggestion otherwise. In arguing against the role of faith in science, however, Siegel ironically embraces a faith-based view of science. His perspective is faith-based not because it has ties to organized religion, obviously, but rather because it is rooted in an idealization of science disconnected from the actual evidence on scientific practice. Siegel mythologizes scientists, seeing them as impersonal and unbiased arbiters of truth. Similar to any other thought-impairing fundamentalism, the faith-based view of science, if too widespread, is antithetical to the practice of democracy.

Individual scientists, being human, fall prey to innumerable biases, conflicts of interest, motivated reasoning and other forms of impaired inquiry. It sanctifies them to expect otherwise. Drug research, for instance, is a tangled thicket of financial conflicts of interest, wherein some scientists go to bat for pharmaceutical companies in order to prevent generics from coming to market and put their names on articles ghost-written by corporations. Some have wondered if scientific medical studies can be trusted, given that many, if not most, are so poorly designed. Siegel, of course, would likely respond that the above cases are simply pathological cases science, which will hopefully be eventually excised from the institution of science as if they were a malignant growths. He consistently tempers his assertions with an appeal to what a “good scientist” would do: “There [is no] such a thing as a good scientist who won’t revise their beliefs in the face of new evidence” claims Siegel. Rather go the easy route and simply charge him with committing a No True Scotsman fallacy, given that many otherwise good scientists often appear to hold onto their beliefs despite new evidence, it is better to question whether his understanding of “good” science stands up to close scrutiny. The image of scientists as disinterested and impersonal arbiters of truth, immediately at the ready to adjust their beliefs in response to new evidence, is not only at odds with the last fifty years of the philosophy and social study of science, it also conflicts with what scientists themselves will say about “good science.” In Ian Mitroff’s classic study of Apollo program scientists investigating the moon and its origins, one interviewed scientist derided what Siegel presents as good science as a “fairy tale,” noting that most of his colleagues did not impersonally sift through evidence but looked explicitly for what would support their views. Far from seeing it as pathological, however, one interviewee stated “bias has a role in science and serves it well.” Mitroff’s scientists argued that ideally disinterested scientists would fail to have the commitment to see their theories through difficult periods. Individual scientists need to have faith that they will persevere in the face of seemingly contrary evidence in order to do the work necessary to defend their theories. Without this bias-laden commitment, good theories would be thrown away prematurely. Further grasping why scientists, in contrast to their cheerleaders in popular media, would defend bias as often good for science requires recognizing that the faith-based understanding of science is founded upon a mistaken view of objectivity. Far too many people see objectivity as inhering within scientists when it really exists between scientists. As political scientist Aaron Wildavsky noted, “What is wanted is not scientific neuters but scientists with differing points of view and similar scientific standards…science depends on institutions that maintain competition among scientists and scientific groups who are numerous, dispersed and independent.” Science does not progress because individual scientists are more angelic human beings who can somehow enter a laboratory and no longer see the world with biased eyes. Rather, science progresses to the extent that scientists with diverse and opposing biases meet in disagreement. Observations and theories become facts not because they appear obviously true to unbiased scientists but because they have been met with scrutiny from scientists with differing biases and the arguments for them found to be widely persuasive. Different areas of science have varied in terms of how well they support vibrant and progressive levels of disagreement. Indeed, part of the reason why so many studies are later found to be false is the fact that scientists are not incentivized to repeat studies done by their colleagues; such studies are generally not publishable. Moreover, entire fields have suffered from cultural biases at one time or another. The image of the human egg as a passive “damsel in distress” waiting for a sperm to penetrate her persisted in spite of contrary evidence partly because of a traditional male bias within the biological sciences. Similar biases were discovered in primatology and elsewhere as scientific institutions became more diverse. Without enterprising scientists asking seemingly heretical questions of what appears to be “sound science” on the basis of sometimes meager evidence, entrenched cultural biases masquerading as scientific facts might persist indefinitely. The recognition that scientists often exhibit flawed and motivated reasoning, bias, personal commitments and the exercise of faith nearly as much as anyone else is important not merely because it is a more scientific understanding of science, but also because it is politically consequential. If citizens see scientists as impersonal arbiters of truth, they are likely to eschew subjecting science to public scrutiny. Political interference in science might seem undesirable, of course, when it involves creationists getting their religious views placed alongside evolution in high school science books. Nevertheless, as science and technology studies scholars Edward Woodhouse and Jeff Howard have pointed out, the belief that science is value-neutral and therefore best left up to scientists has enabled chemists (along with their corporate sponsors) to churn out more and more toxic chemicals and consumer products. Americans’ homes and environments are increasingly toxic because citizens leave the decision over the chemistry behind consumer products up to industrial chemists (and their managers). Less toxic consumer products are unlikely to ever exist in significant numbers so long as chemical scientists are considered beyond reproach. Science is far too important to be left up to an autonomous scientific clergy. Dispensing with the faith-based understanding proffered by Siegel is the first step toward a more publically accountable and more broadly beneficial scientific enterprise. Looking upon all the polarized rhetoric concerning vaccines, GMO crops, climate change, and processed foods one might be tempted to conclude that the American status quo is under attack by a fervent anti-science movement. Indeed, it is not hard to find highly educated and otherwise intelligent people making just that claim in popular media. To some, that proposition probably seems commonsensical if not blatantly obvious. Why else would people be skeptical of all these advances in medical, climate, and agricultural sciences? However, looking more closely at the style of argumentation utilized by critics undermines the claim that they are “anti-science.” Rather, if there is any bias to popular deliberation regarding the risks regarding vaccines, climate change, and GMO crops it is a widespread allergy to engaging in political talk about values.

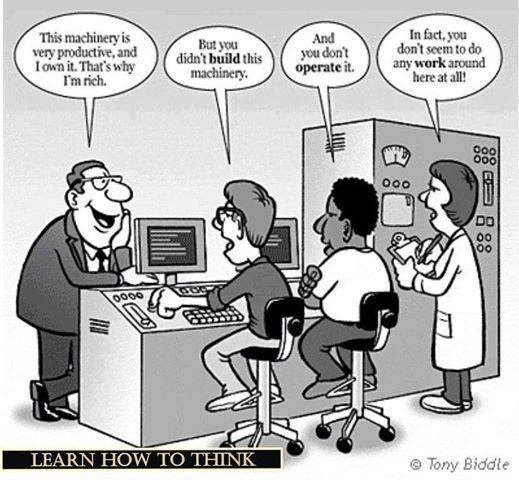

Consider Vani Hari, aka “Food Babe.” Her response to a take-down piece in Gawker is filled with references to studies and links to groups like Consumers Union, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Environmental Working Group, who do employ people with scientific credentials and conduct tests. Groups concerned with potential adverse affects from vaccines, similarly, have their own scientists to fall back on and draw upon highly skeptical and scientific language to highlight uncertainties and as-of-yet undone studies that might help settle safety concerns. If opponents were truly anti-science, they would not exert so much effort to mobilize scientific rhetoric and expertise. Of course, there is still the question of whose expertise is or should be relevant as well as whether or not participants in the debate are attempting a fair and charitable interpretation of available evidence. Nevertheless, the claim that the debate is a result of a split between pro and anti-science factions is pretty much incoherent, if not deluded. Contrary to recurring moral panics about the supposed emergence of polarized anti-scientism, American scientific controversies are characterized by a surprising amount of agreement. No one seems to be in disagreement over the presumption that debate about GMO crops, vaccines, processed foods, and other controversial instances of technoscience should be settled by scientific facts. Even creationists have leaned heavily on a scientific-sounding use of information theory to try to legitimate so-called “intelligent design.” Regardless, this agreement, in turn, rests on an unquestioned assumption that these are even issues that can be settled by science. Both the pro and the con sides are in many ways radically pro-science. Because of this pervasive and unstated agreement, the very real value disagreements that drive these controversies are left by the wayside in favor of endless quibbling over what “the facts” really are. Given the experimenter’s regress, the reality that experimental tests and theories are wrought with uncertainties and unforeseen complexities but are nevertheless relied upon to validate each other, there is always some room for both doubt and confirmation bias in nearly all scientific findings. Of course, doubt is usually mobilized selectively by each side in controversies in ways that mirror their underlying value commitments. Those who tend to view developments within modern science as almost automatically amounting to human progress inevitably find some way to depict opponents as out of touch with the scientific method or using improper methodology. Critics of GMOs or pesticides, for their part, routinely claim to find similar inadequacies in existing safety studies. Additional scientific research, moreover, often only uncovers additional uncertainties; more science can just as often make controversies even more intractable. Therefore, I think that Americans would be better off if social movements were more anti-science. Of course, I do not mean that they would totally disavow the benefits of looking at things scientifically or the more unambiguous benefits of contemporary technoscience. Instead, what I mean is that such groups would reject the assumption that all issues should be viewed, first and foremost, scientistically. Underneath most, if not all, public scientific controversies are real disagreements that relate to values and power. Vaccine critics, rightly or wrongly, are motivated by concerns about a felt loss of liberty regarding their abilities to make health decisions for their children in an age of seemingly pervasive risk. Advocates for more organic farming and fewer petroleum-derived residues on their food and in eco-systems are not only concerned about health risks but the lack of input they have regarding what goes into the products they ingest. The real debate should concern to what extent the technoscientific experts who create the potentially risky and nearly unavoidable products that fill our houses, break down into our local watersheds, and end up in our bloodstreams (along with their allies in business and government) are sufficiently publically accountable. Advocacy groups, however, are caught in a Catch-22. As long as the main legitimacy-imparting public language is scientistic, those who fill their discourse primarily with a consideration of values will probably have a hard time getting heard. Nevertheless, incremental gains could be had if at least some people endeavored to talk to friends, family, and acquaintances about these matters differently: in more explicitly political ways. Those who support mandatory vaccination would do better to talk about the rights of parents of infants and the elderly to not have worry under the specter of previously eradicated and potentially deadly diseases than to claim a level of certitude about vaccine risk they cannot possibly possess. Advocates of organic farming would do well to frame their opposition to GMOs with reference to questions concerning who owns the means of producing food, who primarily benefits, and who has the power to decide which agricultural products are safe. Far too many citizens talk as if they believe science can do their politics for them. It is about time we put that belief to rest. 8/4/2014 Why Are Scientists and Engineers Content to Work for Scraps when MBAs get a Seat at the Table?Read Now Report from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Why should it be that some of the most brilliant and highly educated people I know are forced to beg for jobs and justify their work to managers who, in all likelihood, might have spent a greater part of their business program drunk than studying? Sure there are probably some useful tasks that managers and supervisors perform, and some of them are no doubt perfectly wonderful people. Nevertheless, why should they sit at the top of the hierarchy of the contemporary firm while highly skilled technologists just do what they are told? Why should those who design and build new technologies or solve tenacious scientific problems receive a wage and not a large share in the wealth they help generate? Most importantly, why do so many highly skilled and otherwise intelligent people put up with this situation? There is nothing natural about MBAs and other professional managers running a firm like a captain of ship. As Harvard economist Stephen Marglin illustrated so well, the emergence of that hierarchical system had little to do with improvements in technological efficiency or competitive superiority but rather that it better served the interests of capitalist owners. What bosses “do” is maximize the benefits accruing to capitalists at the expense of workers. Bosses have historically and continue to do this by minimizing the scope each individual worker has in the firm and inserting themselves (i.e., management) as the obligatory intermediary for even the most elementary of procedures. This allows them to better surveil and discipline workers for the benefit of owners. Most highly skilled workers will probably recognize this if they reflect on all those seemingly pointless memos they are forced to read and write. Of course, some separation of labor (and writing of memos) is necessary for achieving efficient production processes, but the current power arrangement ensures that exactly how any process ends up being partitioned is ultimately decided by and for the benefit of managers and owners prior to any consideration of workers’ interests.

Even if one were not bothered by the life-sucking monotony of many jobs inflicted by a strict separation of labor, there is still little reason why the person in charge of coordinating everyone’s individual tasks ought to rule with almost unquestioned authority. This is a particularly odd arrangement for tech firms, given that scientists and engineers are highly skilled workers whose creative talents make up the core the company’s success. Moreover, these workers only receive a wage while others (e.g., venture capitalists, shareholders and select managers) get the lion’s share of the generated wealth: “Thanks for writing the code for that app that made us millions. Here, have a bonus and count yourself lucky to have a job.” Although frequently taken to be “just the way things are,” it need not be the case that the totality of the profits of innovation so disproportionately accrue to shareholders and select managers. Neither does one need look as far away as socialist nations in order to recognize this. Family-owned and “closely held” corporations in the United States already forgo lower rates of monetary profit in order to enjoy non-monetary benefits and yet remain competitive. For instance, Hobby Lobby, recently made infamous for other reasons, closes its stores on Sundays. They give up sales to competitors like Michaels because those running the firm believe that workers ought to have a guaranteed day in their schedule to spend time with friends and loved ones. Companies like Chick-Fil-A, Wegman’s and others pay their workers more livable wages and/or help fund their college educations, all practices unlikely to maximize shareholder value by any stretch of the imagination. At the same time, the hiring process for many managers does not lend much credence to the view that their skills alone make the difference between a successful or unsuccessful company. Michael Church, for instance, recently posted an account of the differences between applying to tech firm as a software engineer versus a manager. When interviewing as a software engineer, the applicant was subjected to a barrage of doubts about their skills and qualifications. The burden of proof was laid on the applicant to prove themselves worthy. In contrast, when applying for a management position, the same applicant was seen as “already part of the club” and was targeted with hardly any scrutiny at all. This is, of course, but one example. I encourage readers to share their own experiences in the comments section. Regardless, I suspect that if management is regularly treated like a club for those with the right status rather than the right competencies, their skills may not be so scarce or essential as to justify their higher wages, stake in company assets and discretion in decision-making. Young, highly skilled workers seem totally unaware of the power they could have in their working lives, if enough of them strove to seize it. I am not talking about unionization, though that could also be helpful. Instead, I am suggesting that scientists and engineers could own and manage their own firms, reversing (or simply leveling) the hierarchy with their current business-major overlords. Doing so would not be socialism but rather economic democracy: a worker cooperative. Workers outside the narrow echelon of managers and distant venture capitalists could have stake in the ownership of capital and thus power in the firm, making it much more likely that their interests are better reflected in decisions about operations and longer-term business plans. There is no immediately obvious reason why scientists and engineers could not start their own worker cooperatives. In fact, there are cases of workers less skilled and educated than the average software engineer helping govern and earning equity in their companies. The Evergreen cooperative in Cleveland, Ohio, for instance, consists of a laundry – mostly serving a nearby hospital, a greenhouse and a weatherization contractor. A small percentage of each worker’s salary goes into owning a stake in the cooperative, amounting to about $65,000 in wealth in roughly eight years. Workers elect their own representation to the firm’s board and thus get a say in its future direction and daily operation. Engineers, scientists and other technologists are intelligent enough to realize that the current “normal” business hierarchy offers them a raw deal. If laundry workers and gardeners can cooperatively run a profitable business while earning wealth, not merely a wage, certainly those with the highly specialized, creative skills always being extolled as being the engine of the “new knowledge economy” could as well. The main barrier is psychological. Engineers, scientists and other technologists have been encultured to think that things work out best if they remain mere problem solvers – more cynical observers might say overhyped technicians. Maybe they believe they will be one of the lucky ones to work somewhere with free pizza, breakout rooms and a six figure salary, or maybe they think they will eventually break into management themselves. Of course there is also the matter of the start-up capital that any tech firm needs to get off the ground. Yet, if enough technologists started their own cooperative firms, they could eventually pool resources to finance the beginnings of other cooperative ventures. All it would take is a few dozen enterprising people to show their peers that they do not have to work for scraps (even if there are sometimes large paychecks to go with that free pizza). Rather, they could take a seat at the table. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed