|

America’s nuclear energy situation is a microcosm of the nation’s broader political dysfunction. We are at an impasse, and the debate around nuclear energy is highly polarized, even contemptuous. This political deadlock ensures that a widely disliked status quo carries on unabated. Depending on one’s politics, Americans are left either with outdated reactors and an unrealized potential for a high-energy but climate-friendly society, or are stuck taking care of ticking time bombs churning out another two thousand tons of unmanageable radioactive waste every year

Continue reading at The New Atlantis

“Gift to Big Oil.” “Toxic.” “Dangerous.” Planet of the Humans, which criticizes the idea that green energy will solve the climate crisis, has made a lot of people very upset. Some critics have gone so far as to equate its argument with climate denialism or demand that the film be taken down. While the documentary is far from perfect, far worse is the shallowness of the discussion about the film. Both Planet of the Humans and the critical response of it illustrate everything that is wrong with our fact-obsessed culture, one in which perspectives on controversial topics aren’t honestly engaged with but merely “debunked.”

Most of the critics have zeroed in on parts of the film that are outdated or potentially misleading. The 8% efficient solar panels shown early on of the documentary are now 22% efficient. Most electrical grids are dominated by natural gas rather than coal, greatly improving the relative carbon footprint of an electric car. While the share of different renewables in Germany’s total energy mixture—which includes transportation and home heating—do hover around the single digits, altogether they comprise some 40% of electricity production. But the facts used in the rebuttals are usually themselves only slightly less simplistic or equivalently misleading. Life-cycle analyses of electric vehicles (EVs) show that they have approximately a 30% advantage in cradle-to-grave greenhouse gas emissions, but their impact on water sources and aquatic life is higher because they require exotic mined materials. So, while critics do have a point that the carbon outlook on electric vehicles are better than what director Jeff Gibbs implies, they don’t actually provide much to counter his argument that EVs may not actually be good enough to deliver on promised environmental outcomes. Will their carbon advantage balance out the harms if we end up building billions of them? Likewise, isn’t it deceptive to only use electricity production statistics to tout the progress made by renewables, since all energy use outputs CO2? Neither do critics prove themselves to be dispassionate fact arbiters when they cherry pick parts of the documentary to shore up their own narrative of it as misinformed energy heresy. Much has been made of co-producer Ozzie Zehner’s statement in front of the Ivanpah concentrated solar facility: "You use more fossil fuels to do this than you're getting benefit from it. You would have been better off just burning fossil fuels in the first place, instead of playing pretend." Critics aiming at a “gotcha” moment have used this quote to portray Zehner as so obtuse as to believe that no solar technology has a better carbon footprint than fossil fuels. The more reasonable interpretation is, of course, that he’s talking specifically about the Ivanpah solar facility that he’s standing right in front of at that very moment. At this point, critics’ claim to the moral or factual high ground starts to seem suspect. The underlying problem with the whole debate is the widespread belief that “the facts” will tell us that we are on the right track, that clear-eyed carbon accounting will clear out all the messy political and moral debates inherent in the climate crisis. If only. We get simple answers only by making simplifying assumptions and using reductive metrics, blinding ourselves to the multifaceted ways that our technologies often harm both people and the environment and obscuring far deeper questions about what humanity’s relationship with the planet should be. The focus on “debunking” distracts us from the recognition that the climate crisis poses far more complex question than the mere carbon footprint of alternative energy technologies, that whenever we generate energy we commit ourselves to doing harm. The framing of PVs and wind turbines as “green,” “renewable,” and “zero-carbon” distracts us from how all energy technologies lead to deaths (animal and human), ecosystem destruction, massive levels of extraction and processing of raw materials, pollution, and even the disruption of our experience of non-human spaces. If we get too caught up in the dream of green-energy-fueled progress, we risk sleepwalking through the innovation process, ignoring deeper problems until it is too late and setting ourselves up to repeat the same kind of mistake that we made with fossil fuels. In massively expanding wind or tidal energy, will the potential effects on wildlife be worth it? Is it a fair trade to give up the ability to climb a mountaintop in Vermont and hear nothing but the rustling of the trees? Will the probable environmental and sociopolitical consequences of mining rare earth metals in South American and African countries be a worthy sacrifice? Even then, it is unclear if promises of a 100% renewable consumer society can ever be delivered. Even though a life-cycle analysis of an individual car or photovoltaic unit can produce a nice-looking number, things become far more complex at higher scales. Take Stanford professor Mark Jacobson’s proposal, which would require nearly two billion roof-top solar installations along with thousands upon thousands of tidal turbines, Ivanpah-like facilities, and geothermal plants. One would think they were reading a proposal to terraform Mars, given the sheer material requirements of such an endeavor. And even then his proposal has been pilloried for simplistic assumptions about the power grid, environmental constraints on hydropower capacity, and land use. Gibbs’s core worry that the green energy dream may be a deceptive illusion remains an important one, for the dream remains but a speculative future, one that we are by no means guaranteed to achieve. To be fair to the critics, the documentary tends to be pretty ham-fisted, and that main point gets lost as Gibbs chases a tale of corporate greed and corruption. My sense of the film is that Moore’s and Gibbs’s voices are too loud, and that the perspective co-producer and environmental scholar Ozzie Zehner is only present in disjointed fragments. For those who feel the urge to condemn the documentary to the dustbin, I recommend taking a look at Zehner’s 2012 Green Illusions. Surprising as it may seem to viewers of Planet of the Humans, Zehner actually concludes halfway into his book that he believes that the world will eventually be powered by renewable energy, just not in the way that we usually think. He contends that the least expensive and most environmentally beneficent way to shut down a coal plant is to not have to replace it with anything. That is, energy reduction beats green energy any day of the week. But the dominant media narrative is suffuse with speculative ecomodernist hopes and dreams of a world almost entirely unchanged from what we enjoy today, albeit powered by PVs and wind turbines. So, we dedicate far too little money and effort to all the ways that we could use far less energy, needing not only fewer fossil fuel plants but also significantly less green energy to replace it. Zehner’s book further parts ways from Planet of the Humans by actually providing solutions. A key part of his recommendations is that none of them actually require us to “sacrifice” for the climate. There’s no bleak demand for energy “austerity” here. For example, he advocates designing cities to require far less driving and be made up of denser, more energy thrift housing. Such neighborhoods would provide residents with a level of community engagement that they likely haven’t enjoyed since college (if ever) and a quality of life difficult to find in most contemporary American cities. Especially noteworthy is Zehner’s answer to the population question. Because Gibbs leaves the viewer to read between the lines when he proposes population control, critics have taken it upon themselves to assume the worst possible interpretation, linking Gibbs’s suggestion with something called “ecofascism” and “far-right hate groups.” (Does that also count as misinformation or is it merely misleading?) Despite the left-wing tendency to dismiss the idea inherently racist and “problematic,” Zehner’s proposal for population control couldn’t be more progressive: gender equality. He simply notes that cultures that afford the equal right of women and girls to go to school and have careers produce fewer babies. That’s certainly not ecofascist by any stretch of the imagination. But why wasn’t that in the film? So, the problem with Planet of the Humans isn’t so much that it is factually flawed. (I mean, if other large-scale technological controversies are any guide, many critics would use even more minor empirical failings to dismiss an inconvenient perspective in its entirety.) Rather, the real limitation of the film is that it lacks a compelling vision of the future. It too easily allows others—whether it be “big oil” or nuclear energy fanatic Michael Shellenberger—opportunistically fill in the void with their own self-serving conclusions. It allows critics to dismiss it as a paean to ecofascim or nihilism. But Gibbs’s film still alerts us to something important: the need to pause and reflect upon exactly where all this “green” industrial energy activity is supposed take us. But will the critics be too preoccupied with “getting the facts right” to really hear it?

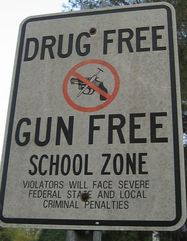

There have been no shortage of (mainly conservative) pundits and politicians suggesting that the path to fewer school shootings is armed teachers—and even custodians. Although it is entirely likely that such recommendations are not really serious but rather meant to distract from calls for stricter gun control legislation, it is still important to evaluate them. As someone who researches and teaches about the causes of unintended consequences, accidents, and disasters for a living, I find the idea that arming public school workers will make children safer highly suspect—but not for the reasons one might think.

If there is one commonality across myriad cases of political and technological mistakes, it would be the failure to acknowledge complexity. Nuclear reactors designed for military submarines were scaled up over an order of magnitude to power civilian power plants without sufficient recognition of how that affected their safety. Large reactors can get so hot that containing a meltdown becomes impossible, forcing managers to be ever vigilant to the smallest errors and install backup cooling systems—which only increased difficult to manage complexities. Designers of autopilot systems neglected to consider how automation hurt the abilities of airline pilots, leading to crashes when the technology malfunctioned and now-deskilled pilots were forced to take over. A narrow focus on applying simple technical solutions to complex problems generally leads to people being caught unawares by ensuing unanticipated outcomes. Debate about whether to put more guns in schools tends to emphasize the solution’s supposed efficacy. Given that even the “good guy with a gun” best positioned to stop the Parkland shooting failed to act, can we reasonably expect teachers to do much better? In light of the fact that mass shootings have even occurred at military bases, what reason do we have to believe that filling educational institutions with armed personnel will reduce the lethality of such incidents? As important as these questions are, they divert our attention to the new kinds of errors produced by applying a simplistic solution—more guns—to a complex problem. A comparison with the history of nuclear armaments should give us pause. Although most American during the Cold War worried about potential atomic war with the Soviets, Cubans, or Chinese, much of the real risks associated with nuclear weapons involve accidental detonation. While many believed during the Cuban Missile Crisis that total annihilation would come from nationalistic posturing and brinkmanship, it was actually ordinary incompetence that brought us closest. Strategic Air Command’s insistence on maintaining U2 and B52 flights and intercontinental ballistic missiles tests during periods of heightened risked a military response from the Soviet Union: pilots invariably got lost and approached Soviet airspace and missile tests could have been misinterpreted to be malicious. Malfunctioning computer chips made NORAD’s screens light up with incoming Soviet missiles, leading the US to prep and launch nuclear-armed jets. Nuclear weapons stored at NATO sites in Turkey and elsewhere were sometimes guarded by a single American soldier. Nuclear armed B52s crashed or accidently released their payloads, with some coming dangerously close to detonation. Much the same would be true for the arming of school workers: The presence and likelihood routine human error would put children at risk. Millions of potentially armed teachers and custodians translates into an equal number of opportunities for a troubled student to steal weapons that would otherwise be difficult to acquire. Some employees are likely to be as incompetent as Michelle Ferguson-Montogomery, a teacher who shot herself in the leg at her Utah school—though may not be so lucky as to not hit a child. False alarms will result not simply in lockdowns but armed adults roaming the halls and, as result, the possibility of children killed for holding cellphones or other objects that can be confused for weapons. Even “good guys” with guns miss the target at least some of the time. The most tragic unintended consequence, however, would be how arming employees would alter school life and the personalities of students. Generations of Americans mentally suffered under Cold War fears of nuclear war. Given the unfortunate ways that many from those generations now think in their old age: being prone to hyper-partisanship, hawkish in foreign affairs, and excessively fearful of immigrants, one worries how a generation of kids brought up in quasi-militarized schools could be rendered incapable of thinking sensibly about public issues—especially when it comes to national security and crime. This last consequence is probably the most important one. Even though more attention ought to be paid toward the accidental loss of life likely to be caused by arming school employees, it is far too easy to endlessly quibble about the magnitude and likelihood of those risks. That debate is easily scientized and thus dominated by a panoply of experts, each claiming to provide an “objective” assessment regarding whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks. The pathway out of the morass lies in focusing on values, on how arming teachers—and even “lockdown” drills— fundamentally disrupts the qualities of childhood that we hold dear. The transformation of schools into places defined by a constant fear of senseless violence turns them into places that cannot feel as warm, inviting, and communal as they otherwise could. We should be skeptical of any policy that promises greater security only at the cost of the more intangible features of life that make it worth living. 10/6/2017 Why the Way We Talk About Politics Will Ensure that Mass Shootings Keep HappeningRead Now

After news broke of the Las Vegas shooting, which claimed some 59 lives, professional and lay observers did not hesitate in trotting out the same rhetoric that Americans have heard time and time again. Those horrified by the events demanded that something be done; indeed, the frequency and scale of these events should be horrifying. Conservatives, in response, emphasized evidence for what they see as the futility of gun control legislation. Yet it is not so much gun control itself that seems futile but rather our collective efforts to accomplish almost any policy change. The Onion satirized America's firearm predicament with the same headline used after numerous other shootings: “‘No Way to Prevent This,’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens.” Why is it that we Americans seem so helpless to effect change with regard to mass shootings? What explains our inability to collectively act to combat these events?

Political change is, almost invariably, slow and incremental. Although the American political system is, by design, uniquely conservative and biased toward maintaining the status quo, that is not the only reason why rapid change rarely occurs. Democratic politics is often characterized as being composed by a variety of partisan political groups, all vying with one another to get their preferred outcome on any given policy area: that is, as pluralistic. When these different partisan groups are relatively equal and numerous, change is likely to be incremental because of substantial disagreements between these groups and the fact that each only has a partial hold on power. Relative equality among them means that any policy must be a product of compromise and concession—consensus is rarely possible. Advocates of environmental protection, for instance, could not expect to convince governments to immediately dismantle of coal-fired power plants, though they might be able to get taxes, fines, or subsidies adjusted to discourage them; the opposition of industry would prevent radical change. Ideally, the disagreements and mutual adjustments between partisans would lead to a more intelligent outcome than if, say, a benevolent dictator unilaterally decided. While incremental policy change would be expected even in an ideal world of relatively equal partisan groups, things can move even slower when one or more partisan groups are disproportionately powerful. This helps explain why gun control policy—and, indeed, environmental protections, and a whole host of other potentially promising changes—more often stagnates than advances. Businesses occupy a relatively privileged position compared to other groups. While the CEO of Exxon can expect the president’s ear whenever a new energy bill is being passed, average citizens—and even heads of large environmental groups—rarely get the same treatment. In short, when business talks, governments listen. Unsurprisingly the voice of the NRA, which is in essence a lobby group for the firearm industry, sounds much louder to politicians than anyone else’s—something that is clear from the insensitivity of congressional activity to widespread support for strengthening gun control policy. But there is more to it that just that. I am not the first person to point out that the strength of the gun lobby stymies change. Being overly focused the disproportionate power wielded by some in the gun violence debate, we miss the more subtle ways in which democratic political pluralism is itself in decline. Another contributing factor to the slowness of gun policy change is the way Americans talk about issues like gun violence. Most news stories, op-eds, and tweets are laced with references to studies and a plethora of national and international statistics. Those arguing about what should be done about gun violence act as if the main barrier to change has been that not enough people have been informed of the right facts. What is worse is that most participants seem already totally convinced of the rightness of their own version or interpretation of those facts: e.g., employing post-Port Arthur Australian policy in the US will reduce deaths or restrictive gun laws will lead to rises in urban homicides. Similar to two warring nations both believing that they have God uniquely on their side, both sides of the gun control debate lay claim to being on the right side of the facts, if not rationality writ large. The problem with such framings (besides the fact that no one actually knows what the outcome would be until a policy is tried out) is that anyone who disagrees must be ignorant, an idiot, or both. That is, exclusively fact-based rhetoric—the scientizing of politics—denies pluralism. Any disagreement is painted as illegitimate, if not heretical. Such as view leads to a fanatical form of politics: There is the side with “the facts” and the side that only needs informed or defeated, not listened to. If “the facts” have already pre-determined the outcome of policy change, then there is no rational reason for compromise or concession, one is simply harming one’s own position (and entertaining nonsense). If gun control policy is to proceed more pluralistically, then it would seem that rhetorical appeals to the facts would need dispensed with—or at least modified. Given that the uncompromising fanaticism of some of those involved seems rooted in an unwavering certainty regarding the relevant facts, emphasizing uncertainty would likely be a promising avenue. In fact, psychological studies find that asking people to face the complexity of public issues and recognize the limits of their own knowledge leads to less fanatical political positions. Proceeding with a conscious acknowledgement of uncertainty would have the additional benefit of encouraging smarter policy. Guided by an overinflated trust that a few limited studies can predict outcomes in exceedingly complex and unpredictable social systems, policy makers tend to institute rule changes or laws with no explicit role for learning. Despite that even scientific theories are only tentatively true, ready to be turned over by evermore discerning experimental tests or shift in paradigm, participants in the debate act as if events in Australia or Chicago have established eternal truths about gun control. As a result, seldom is it considered that new policies could be tested gradually, background check and registration requirements that become more stringent over time or regional rollouts, with an explicit emphasis on monitoring for effectiveness and unintended consequences—especially consequences for the already marginalized. How Americans debate issues like gun control would be improved in still other ways if the narrative of “the facts” were not so dominant in people’s speech. It would allow greater consideration of values, feelings, and experiences. For instance, gun rights advocates are right to note that semiautomatic “assault” weapons are responsible for a minority of gun deaths, but their narrow focus on that statistical fact prevents them from recognizing that it is not their “objective” danger that motivates their opponents but their political riskiness. The assault rifle, due to its use in horrific mass shootings, has come to symbolize American gun violence writ large. For gun control advocates it is the antithesis of conservatives’ iconography of the flag: It represents everything that is rotten about American culture. No doubt reframing the debate in that way would not guarantee more productive deliberation, but it would at least enable political opponents some means of beginning to understand each others' position. Even if I am at least partly correct in diagnosing what ails American political discourse, there remains the pesky problem of how to treat it. Allusions to “the facts,” attempts to leverage rhetorical appeals to science for political advantage, have come to dominant political discourse over the course of decades—and without anyone consciously intending or dictating it. How to effect movement in the opposite direction? Unfortunately, while some social scientists study these kinds of cultural shifts as they occur throughout history, practically none of them research how beneficial cultural changes could be generated in the present. Hence, perhaps the first change citizens could advocate for would be more publicly responsive and relevant social research. Faced with an increasingly pathological political process and evermore dire consequences from epochal problems, social scientists can no longer afford to be so aloof; they cannot afford to simply observe and analyze society while real harms and injustices continue unabated.

Although Elon Musk's recent cryptic tweets about getting approval to build a Hyperloop system connecting New York and Washington DC are likely to be well received among techno-enthusiasts--many of whom see him as Tony Stark incarnate--there are plenty of reasons to remain skeptical. Musk, of course, has never shied away from proposing and implementing what would otherwise seem to be fairly outlandish technical projects; however, the success of large-scale technological projects depends on more than just getting the engineering right. Given that Musk has provided few signs that he considers the sociopolitical side of his technological undertakings with the same care that he gives the technical aspects (just look at the naivete of his plans for governing a Mars colony), his Hyperloop project is most likely going to be a boondoggle--unless he is very, very lucky.

Don't misunderstand my intentions, dear reader. I wish Mr. Musk all the best. If climate scientists are correct, technological societies ought to be doing everything they can to get citizens out of their cars, out of airplanes, and into trains. Generally I am in favor of any project that gets us one step closer to that goal. However, expensive failures would hurt the legitimacy of alternative transportation projects, in addition to sucking up capital that could be used on projects that are more likely to succeed. So what leads me to believe that the Hyperloop, as currently envisioned, is probably destined for trouble? Musk's proposals, as well as the arguments of many of his cheerleaders, are marked by an extreme degree of faith in the power of engineering calculation. This faith flies in the face of much of the history of technological change, which has primarily been a incremental, trial-and-error affair often resulting in more failures than success stories. The complexity of reality and of contemporary technologies dwarfs people's ability to model and predict. Hyman Rickover, the officer in charge of developing the Navy's first nuclear submarine, described at the length the significant differences between "paper reactors" and "real reactors," namely that the latter are usually behind schedule, hugely expensive, and surprisingly complicated by what would normally be trivial issues. In fact, part of the reason the early nuclear energy industry was such a failure, in terms of safety oversights and being hugely over budget, was that decisions were dominated by enthusiasts and that they scaled the technology up too rapidly, building plants six times larger than those that currently existed before having gained sufficient expertise with the technology. Musk has yet to build a full-scale Hyperloop, leaving unanswered questions as to whether or not he can satisfactorily deal with the complications inherent in shooting people down a pressurized tube at 800 miles an hour. All publicly available information suggests he has only constructed a one-mile mock-up on his company's property. Although this is one step beyond a "paper" Hyperloop, a NY to DC line would be approximately 250 times longer. Given that unexpected phenomena emerge with increasing scale, Musk would be prudent to start smaller. Doing so would be to learn from the US's and Germany's failed efforts to develop wind power in 1980s. They tried to build the most technically advanced turbines possible, drawing on recent aeronautical innovations. Yet their efforts resulted in gargantuan turbines that failed often within tens of operating hours. The Danes, in contrast, started with conventional designs, incrementally scaling up designs andlearning from experience. Apart from the scaling-up problem, Musk's project relies on simultaneously making unprecedented advances in tunneling technology. The "Boring Company" website touts their vision for managing to accomplish a ten-fold decrease in cost through potential technical improvements: increasing boring machine power, shrinking tunnel diameters, and (more dubiously) automating the tunneling process. As a student of technological failure, I would question the wisdom of throwing complex and largely experimental boring technology into a project that is already a large, complicated endeavor that Musk and his employees have too little experience with. A prudent approach would entail spending considerable time testing these new machines on smaller projects with far less financial risk before jumping headfirst into a Hyperloop project. Indeed, the failure of the US space shuttle can be partly attributed to the desire to innovate in too many areas at the same time. Moreover, Musk's proposals seem woefully uninformed about the complications that arise in tunnel construction, many of which can sink a project. No matter how sophisticated or well engineered the technology involved, the success of large-scale sociotechnical projects are incredibly sensitive to unanticipated errors. This is because such projects are highly capital intensive and inflexibly designed. As a result, mistakes increase costs and, in turn, production pressures--which then contributes to future errors. The project to build a 2 mile tunnel to replace the Alaska Way Viaduct, for instance, incurred a two year, quarter billion dollar delay after the boring machine was damaged after striking a pipe casing that went unnoticed in the survey process. Unless taxpayers are forced to pony up for those costs, you can be sure that tunnel tolls will be higher than predicted. It is difficult to imagine how many hiccups could stymie construction on a 250 mile Hyperloop. Such errors will invariably raise the capital costs of the project, costs that would need to be recouped through operating revenues. Given the competition from other trains, driving, and flying, too high of fares could turn the Hyperloop into a luxury transport system for the elite. Concorde anyone? Again, while I applaud Musk's ambition, I worry that he is not proceeding intelligently enough. Intelligently developing something like a Hyperloop system would entail focusing more on his own and his organization's ignorance, avoiding the tendency to become overly enamored with one's own technical acumen. Doing so would also entail not committing oneself too early to a certain technical outcome but designing so as to maximize opportunities for learning as well as ensuring that mistakes are relatively inexpensive to correct. Such an approach, unfortunately, is rarely compatible with grand visions of immediate technical progress, at least in the short-term. Unfortunately, many of us, especially Silicon Valley venture capitalists, are too in love with those grand visions to make the right demands of technologists like Musk. It is an understatement to say that the case of Anna Stubblefield is simply controversial. Opinions of the former Rutgers professor, who was recently sentenced to some 10 odd years in prison for the charge of sexually assaulting a disabled man, are highly polarized. When reading comments on recent news stories on the case, one finds not only people who find her absolutely abhorrent but also people who empathize or support her side. No doubt there are important issues to consider regarding the rights of disabled persons, professional ethics, racism, and the nature of consent. However, I want to focus on how the framing of the case as a battle between science and pseudoscience prevents us from sensibly dealing with the politics underlying the issue. The case is strongly shaped by a broader dispute over of the scientific status of “facilitated communication” (FC), a technique claimed by its advocates to allow previously voiceless people with cerebral palsy or autism to speak. As its name suggests, a facilitator helps guide the disabled person’s hand to a keyboard. In the most favorable reading of the practice, the facilitator simply balances out the muscle contractions and lessens the physical barriers to typing. Some see the practice, however, as more than mere assistance: they claim that the facilitator is the one really doing the typing, either consciously or unconsciously. In the former case, FC is a wonderful gift for those suffering from disabilities and their families. In latter reading, facilitators are charlatans, utilizing a pseudoscientific technique to deceive people. "Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations." This latter view seems to have won out in the case of Anna Stubblefield, who claims that DJ--a man with profound physical and suspected mental disabilities—consented to have sex with her via FC. The court rules that FC did not meet the state standards for science. Hence, Stubblefield was unable to mount a much of a defense vis-à-vis FC.

Most people fail to grasp, however, exactly how hard it is to distinguish science and pseudoscience—despite whatever popularizers like Neil DeGrasse Tyson or Bill Nye seem to claim. Science does not simply produce unquestionable facts, rather it is a skilled practice; its capacity to prove truth is always partial, seen far better in hindsight than in the moment. As science and technology studies scholars well illustrate, experiments are incredibly complex—only becoming more so when their results are controversial. The fact that many scientific activities are heavily dependent on the skill of the scientist is on the one hand obvious, but nevertheless eludes most people. Mid-20th century experiments attempting to transfer memories (e.g., fear of the dark, how to run a maze) between planarian worms or mice exemplify this facet of science. Skeptical and supportive scientists went back and forth incessantly over methodological disagreements in trying to determine whether the observed effects were “real,” eventually considering more than 70 separate variables as possible influences on the outcome of memory transfer experiments. Even though some skeptical scientists derided skill-based variables as a so-called “golden hands” argument, there are plenty of areas of science where an experimentalist’s skill makes or breaks an experiment. Biologists, in particular, frequently lament the difficulty of keeping an RNA sample from breaking down or find themselves developing fairly eccentric protocols for getting “good” results out of a Western Blot or bioassay experiment. What some will view as ad-hoc “golden hands” excuses are often simply facets of doing a complex and highly sensitive procedure. A similar dispute over the role of the skill of the practitioner makes FC controversial. After rosy beginnings, skeptical scientists produced results that cast doubt on the technique. Experiments involved the attempt to duplicate text generated with the help of a disabled person’s usual facilitator with a “naïve” facilitator or the asking of questions to which the facilitator wouldn’t know the answer. Indeed, just such an experiment was conducted with DJ, for which both sides claimed victory (Jeff McMahan and Peter Singer, for instance, argue that DJ is more cognitively able than the prosecution would have one believe). As has been the case for other controversial scientific phenomenon, FC only becomes more complex the more deeply one looks into it. Advocates of the method raise their own doubts about studies claiming to disprove the technique’s effectiveness, contending that facilitation requires skills and sensitivities unique to the person being facilitated and that the stressfulness of the testing environment skews the results in the favor of skeptics. There is enough uncertainty surrounding the abilities of those with autism or cerebral palsy to make reasonable arguments either way. Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations. Again, my point is not to try to argue one way or another for FC but to merely point out that the phenomenon under consideration is immensely complex; we simplify it only at our peril. Indeed, the history of science and technology provides plenty of evidence suggesting that we are better off acknowledging that even today’s best science is unlikely to provide sure answers to a controversial debate. Advocates of nuclear energy, for instance, once claimed that their science proved that an accident was a near impossibility, happening perhaps once in ten thousand years. Similarly, some petroleum geology experts have claimed that it is physically impossible for fracking to introduce natural gas and other contaminants to water supplies: there is simply too much rock in between. Yet, an EPA scientist has recently produced fairly persuasive evidence to the contrary. “Settled science” rhetoric has mainly served to shut down inquiry, and the discovery of contrary findings in ensuing decades only adds support to the view that reaching something like scientific certainty is a long and difficult struggle. As a result, scientific controversies are often as much settled politically as scientifically: they are as much battles of rhetoric as facts. Rather than pretend that absolute certitude were possible, what if we proceeded with controversial practices like FC guided by the presumption that we might be wrong about it? What if we assumed that it was possible the method could work—perhaps for a very small percentage of autistics and those born with severe cerebral palsy--but that we are challenged in our ability to know for whom it worked? Moreover, self-deception—like many believe Anna Stubblefield fell prey to—remains a pervasive risk. The situation changes dramatically. Rather than commit oneself to idea that something is either pure truth or complete pseudoscience, the issue can be framed in terms of risk: given that we may be wrong, who might suffer which benefits and harms? How many cases of sham communication via FC balances out the possibility of a non-communicative person losing their voice? In other words, do we prefer false positives or false negatives? Such a perspective challenges people to think more deeply about what matters with respect to FC. Surely the prospect of disabled people being abused or killed because of communication that originates more with the facilitator than the person being facilitated is horrifying. Yet, on the other hand, Daniel Engeber describes meeting families who feel like FC has been a godsend. Even in the scenario in which FC only provides a comforting delusion, is anyone being harmed? A philosophy professor I once knew remarked that he’d take a good placebo over nothing at all any day of the week. On what grounds do we have to deprive people of controversial (even potentially fictitious) treatment if it is not too harmful and potentially increases the well-being of at least some of the people involved? I don’t have an answer to these questions, but I do know that we cannot begin to debate them if we hide behind a simplistic partitioning of all knowledge into either science or pseudoscience, pretending that such designations can do our politics for us Looking upon all the polarized rhetoric concerning vaccines, GMO crops, climate change, and processed foods one might be tempted to conclude that the American status quo is under attack by a fervent anti-science movement. Indeed, it is not hard to find highly educated and otherwise intelligent people making just that claim in popular media. To some, that proposition probably seems commonsensical if not blatantly obvious. Why else would people be skeptical of all these advances in medical, climate, and agricultural sciences? However, looking more closely at the style of argumentation utilized by critics undermines the claim that they are “anti-science.” Rather, if there is any bias to popular deliberation regarding the risks regarding vaccines, climate change, and GMO crops it is a widespread allergy to engaging in political talk about values.

Consider Vani Hari, aka “Food Babe.” Her response to a take-down piece in Gawker is filled with references to studies and links to groups like Consumers Union, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Environmental Working Group, who do employ people with scientific credentials and conduct tests. Groups concerned with potential adverse affects from vaccines, similarly, have their own scientists to fall back on and draw upon highly skeptical and scientific language to highlight uncertainties and as-of-yet undone studies that might help settle safety concerns. If opponents were truly anti-science, they would not exert so much effort to mobilize scientific rhetoric and expertise. Of course, there is still the question of whose expertise is or should be relevant as well as whether or not participants in the debate are attempting a fair and charitable interpretation of available evidence. Nevertheless, the claim that the debate is a result of a split between pro and anti-science factions is pretty much incoherent, if not deluded. Contrary to recurring moral panics about the supposed emergence of polarized anti-scientism, American scientific controversies are characterized by a surprising amount of agreement. No one seems to be in disagreement over the presumption that debate about GMO crops, vaccines, processed foods, and other controversial instances of technoscience should be settled by scientific facts. Even creationists have leaned heavily on a scientific-sounding use of information theory to try to legitimate so-called “intelligent design.” Regardless, this agreement, in turn, rests on an unquestioned assumption that these are even issues that can be settled by science. Both the pro and the con sides are in many ways radically pro-science. Because of this pervasive and unstated agreement, the very real value disagreements that drive these controversies are left by the wayside in favor of endless quibbling over what “the facts” really are. Given the experimenter’s regress, the reality that experimental tests and theories are wrought with uncertainties and unforeseen complexities but are nevertheless relied upon to validate each other, there is always some room for both doubt and confirmation bias in nearly all scientific findings. Of course, doubt is usually mobilized selectively by each side in controversies in ways that mirror their underlying value commitments. Those who tend to view developments within modern science as almost automatically amounting to human progress inevitably find some way to depict opponents as out of touch with the scientific method or using improper methodology. Critics of GMOs or pesticides, for their part, routinely claim to find similar inadequacies in existing safety studies. Additional scientific research, moreover, often only uncovers additional uncertainties; more science can just as often make controversies even more intractable. Therefore, I think that Americans would be better off if social movements were more anti-science. Of course, I do not mean that they would totally disavow the benefits of looking at things scientifically or the more unambiguous benefits of contemporary technoscience. Instead, what I mean is that such groups would reject the assumption that all issues should be viewed, first and foremost, scientistically. Underneath most, if not all, public scientific controversies are real disagreements that relate to values and power. Vaccine critics, rightly or wrongly, are motivated by concerns about a felt loss of liberty regarding their abilities to make health decisions for their children in an age of seemingly pervasive risk. Advocates for more organic farming and fewer petroleum-derived residues on their food and in eco-systems are not only concerned about health risks but the lack of input they have regarding what goes into the products they ingest. The real debate should concern to what extent the technoscientific experts who create the potentially risky and nearly unavoidable products that fill our houses, break down into our local watersheds, and end up in our bloodstreams (along with their allies in business and government) are sufficiently publically accountable. Advocacy groups, however, are caught in a Catch-22. As long as the main legitimacy-imparting public language is scientistic, those who fill their discourse primarily with a consideration of values will probably have a hard time getting heard. Nevertheless, incremental gains could be had if at least some people endeavored to talk to friends, family, and acquaintances about these matters differently: in more explicitly political ways. Those who support mandatory vaccination would do better to talk about the rights of parents of infants and the elderly to not have worry under the specter of previously eradicated and potentially deadly diseases than to claim a level of certitude about vaccine risk they cannot possibly possess. Advocates of organic farming would do well to frame their opposition to GMOs with reference to questions concerning who owns the means of producing food, who primarily benefits, and who has the power to decide which agricultural products are safe. Far too many citizens talk as if they believe science can do their politics for them. It is about time we put that belief to rest. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed