|

Joseph Epstein's recent Wall Street Journal op-ed has been controversial to say the least. While his article is ostensibly penned as a personal letter to the future first lady, Jill Biden, urging her to not so adamantly insist on being called "Doctor", his main focus is on what he sees as the "watering down" of the academic doctorate.

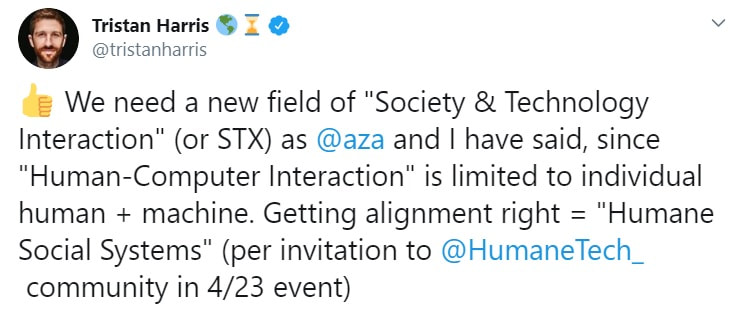

Much of the fury directed at Epstein (and the Wall Street Journal for publishing it) has focused on signs that he was possibly more motivated by sexism than a good faith exploration of what honorific Doctor should mean. He doesn't help his case by being informal to the point of condescension. I mean, he referred to her as "kiddo"! Even though there is a more charitable interpretation: Epstein was playing off of future President Biden's own rhetorical style, that allusion was not clear to nearly all readers. Given both their of their ages and career experience, Jill Biden and Joseph Epstein are obviously peers. If Epstein had wanted more people to take him seriously, he would have avoided seeming to talk down to the future first lady. Put in context of the long hard road that women have had to fight to get themselves taken seriously within fields like academia, his approach is tone deaf, if not worse. I made the mistake on Twitter of trying to engage with the non-sexist part Epstein's thesis. (Yes, I am really that bad at social media). As unsavory as the history of women's credentials being disrespected is, I don't think we should let that history totally overshadow all the other readings of Epstein's argument. Certainly one can argue that discussing whether a PhD really merits being called Doctor should wait until our society is more equal. But that is different than the implication that the question is sexist on its face. Regardless, Epstein's focus is on the increasing ease with which PhDs can be obtained. Exams on Greek and Latin have been dispensed with. More and more PhDs are being minted every year. And honorary doctorates are seemingly handed out to anyone with a sizable donation to offer or even a middling level of celebrity. I think debating the "difficulty" of the degree is the wrong question. Any kind of credential could be made excessively arduous so as to weed out most of the students that attempt it. When I get introduced as Doctor, I usually qualify with a jokey line that my father-in-law used to add, "But not the kind that helps people." The sensibility at the heart of that joke is what lies at the crux of the issue. The extra respect that medical professionals receive is not simply due to the difficulty of obtaining a medical degree. Though, even in that line of thought, it is easy to forget that medical doctors have to take difficult licensing exams, pursue continuing education, and can face potential discipline by a professional governing body--things that PhDs are almost nowhere subject to. Rather, the most important difference between MDs and PhDs is that the former take the Hippocratic Oath. They publicly commit to using their knowledge to help others, although they can and sometimes do fall fall short of that aspiration. The beneficiaries of the work of PhDs are often unclear. The cliché that PhDs are motivated purely by curiosity or knowledge for knowledge's sake obscures a troubling reality. The most reliable benefits of academic work accrue to the researcher themselves (in terms of professional status) and to the small clique of scholars they associate with. No doubt there are exceptions, such as when PhDs admirably choose to work on "applied" problems. But those researchers usually take a big hit professionally by doing so. If PhDs are to earn the Doctor label they should be required to take an analogous oath, one that commits them to using scholarship to benefit at least some small group of people who do not hold PhDs. The attitude that PhDs are entitled to the status of Doctor because they successfully wrote a dissertation, in my mind, inevitably culminates in a narcissistic form of elitism. Status should be a product of how a person serves others, not something awarded because they survived a largely arbitrary academic gauntlet. One of the major oversights that Epstein made in his piece was that he failed to take seriously the difference between a PhD and the degree that Jill Biden actually has, an EdD. Educational doctorate programs are designed to enable graduates to apply their knowledge to situations that are likely to be encountered in real-life educational settings. It is a credential that sets up graduates to do good in the world, not just produce knowledge for other academics. So, in light of my own argument, Jill Biden is more befitting of the Doctor honorific than I am. That is a more exciting and interesting conclusion than I thought would have come from engaging with Epstein's sexist op-ed, one that is worth considering. Back during the summer, Tristan Harris sparked a flurry of academic indignation when he suggested that we needed a new field called “Science & Technology Interaction” or STX, which would be dedicated to improving the alignment between technologies and social systems. Tweeters were quick to accuse him of “Columbizing,” claiming that such a field already existed in the form of Science & Technology Studies (STS) or similar such academic department. So ignorant, amirite?

I am far more sympathetic. If people like Harris (and earlier Cathy O’Neil) have been relatively unaware of fields like Science and Technology Studies, it is because much of the research within these disciplines is mostly illegible to non-academics, not all that useful to them, or both. I really don’t blame them for not knowing. I am even an STS scholar myself, and the table of contents of most issues of my field’s major journals don’t really inspire me to read further. And in fairness to Harris and contrary to Academic Twitter, the field of STX that he proposes does not already exist. The vast majority of STS articles and books dedicate single digit percentages of their words to actually imagining how technology could better match the aspirations of ordinary people and their communities. Next to no one details alternative technological designs or clear policy pathways toward a better future, at least not beyond a few pages at the end of a several-hundred-page manuscript. My target here is not just this particular critique of Harris, but the whole complex of academic opiners who cite Foucault and other social theory to make sure we know just how “problematic” non-academics’ “ignorant” efforts to improve technological society are. As essential as it is to try to improve upon the past in remaking our common world, most of these critiques don’t really provide any guidance for what steps we should be taking. And I think that if scholars are to be truly helpful to the rest of humanity they need to do more than tally and characterize problems in ever more nuanced ways. They need to offer more than the academic equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. In the case of Harris, we are told that underlying the more circumspect digital behavior that his organization advocates is a dangerous preoccupation with intentionality. The idea of being more intentional is tainted by the unsavory history of humanistic thought itself, which has been used for exclusionary purposes in the past. Left unsaid is exactly how exclusionary or even harmful it remains in the present. This kind of genealogical take down has become cliché. Consider how one Gizmodo blogger criticizes environmentalists’ use the word “natural” in their political activism. The reader is instructed that because early Europeans used the concept of nature to prop up racist ideas about Native Americans that the term is now inherently problematic and baseless. The reader is supposed to believe from this genealogical problematization that all human interactions with nature are equally natural or artificial, regardless of whether we choose to scale back industrial development or to erect giant machines to control the climate. Another common problematiziation is of the form “not everyone is privileged enough to…”, and it is often a fair objection. For instance, people differ in their individual ability to disconnect from seductive digital devices, whether due to work constraints or the affordability or ease of alternatives. But differences in circumstances similarly challenge people’s capacity to affordably see a therapist, retrofit their home to be more energy efficient, or bike to work (and one might add to that: read and understand Foucault). Yet most of these actions still accomplish some good in the world. Why is disconnection any more problematic than any other set of tactics that individuals use to imperfectly realize their values in an unequal and relatively undemocratic society? Should we just hold our breaths for the “total overhaul…full teardown and rebuild” of political economies that the far more astute critics demand? Equally trite are references to the “panopticon,” a metaphor that Foucault developed to describe how people’s awareness of being constantly surveilled leads them to police themselves. Being potentially visible at all times enables social control in insidious ways. A classic example is the Benthamite prison, where a solitary guard at the center cannot actually view all the prisoners simultaneously, but the potential for him to be viewing a prisoner at any given time is expected to reduce deviant behavior. This gets applied to nearly any area of life where people are visible to others, which means it is used to problematize nearly everything. Jill Grant uses it to take down the New Urbanist movement, which aspires (though fairly unsuccessfully) to build more walkable neighborhoods that are supportive of increased local community life. This movement is “problematic” because the densities it demands means that citizens are everywhere visible to their neighbors, opening up possibilities for the exercise of social control. Whether not any other way of housing human beings would not result in some form of residential panopticon is not exactly clear, except perhaps by designing neighborhoods so as to prohibit social community writ large. Further left unsaid in these critiques is exactly what a more desirable alternative would be. Or at least that alternative is left implicit and vague. For example, the pro-disconnection digital wellness movement is in need of enhanced wokeness, to better come to terms with “the political and ideological assumptions” that they take for granted and the “privileged” values they are attempting to enact in the world. But what does that actually mean? There’s a certain democratic thrust to the criticism, one that I can get behind. People disagree about what is “the good life” and how to get there, and any democratic society would be supportive of a multitude of them. Yet the criticism that the digital wellness movement seems to center around one vision of “being human,” one emphasizing mindfulness and a capacity to exercise circumspect individual choosing, seems hollow without the critics themselves showing us what should take its place. Whatever the flaws with digital wellness, it is not as self-stultifying as the defeatist brand of digital hedonism implicitly left in the wake of academic critiques that offer no concrete alternatives. Perhaps it is unfair to expect a full-blown alternative; yet few of these critiques offer even an incremental step in the right direction. Even worse, this line of criticism can problematize nearly everything, losing its rhetorical power as it is over-applied. Even academia itself is disciplining. STS has its own dominant paradigms, and critique is mobilized in order to mold young scholars into academics who cite the right people, quote the correct theories, and support the preferred values. My success depends on me being at least “docile enough” in conforming myself to the norms of the profession. I also exercise self-discipline in my efforts to be a better spouse and a better parent. I strive to be more intentional when I’m frustrated or angry, because I too often let my emotions shape my interactions with loved ones in ways that do not align with my broader aspirations. More intentionality in my life has been generally a good thing, so long as my expectations are not so unrealistic as to provoke more anxiety than the benefits are worth. But in a critical mode where self-discipline and intentionality automatically equate to self-subjugation, how exactly are people to exercise agency in improving their own lives? In any case, advocating devices that enable users to exercise greater intentionality over their digital practices is not a bad thing per se. Citizens pursue self-help, meditate, and engage in other individualistic wellness activities because the lives they live are constrained. Their agency is partly circumscribed by their jobs, family responsibilities, and incomes, not to mention the more systemic biases of culture and capitalism. Why is it wrong for groups like Harris’ center to advocate efforts that largely work within those constraints? Yet even that reading of the digital wellness movement seems uncharitable. Certainly Harris’ analysis lacks the sophistication of a technology scholar’s, but he has made it obvious that he recognizes that dominant business models and asymmetrical relations of power underlay the problem. To reduce his efforts to mere individualistic self-discipline is borderline dishonest, though he no doubt emphasizes the parts of the problem he understands best. Of course it will likely take more radical changes to realize the humane technology than Harris advocates, but it is not totally clear whether individualized efforts necessarily detract from people’s ability or the willingness demand more from tech firms and governments (i.e., are they like bottled water and other “inverted quarantines”?). At least that is a claim that should be demonstrated rather than presumed from the outset. At its worst, critical “problematizing” presents itself as its own kind of view from nowhere. For instance, because the idea of nature has been constructed in various biased throughout history, we are supposed to accept the view that all human activities are equally natural. And we are supposed to view that perspective as if it were itself an objective fact rather than yet another politically biased social construction. Various observers mobilize much the same critique about claims regarding the “realness” of digital interactions. Because presenting the category of “real life” as being apart from digital interactions is beset with Foulcauldian problematics, we are told that the proper response is to no longer attempt the qualitative distinctions that that category can help people make—whatever its limitations. It is probably no surprise that the same writer wanting to do away with the digital-real distinction is enthusiastic in their belief that the desires and pleasures of smartphones somehow inherently contain the “possibility…of disrupting the status quo.” Such critical takes give the impression that all technology scholarship can offer is a disempowering form of relativism, one that only thinly veils the author’s underlying political commitments. The critic’s partisanship is also frequently snuck in the backdoor by couching criticism in an abstract commitment to social justice. The fact that the digital wellness movement is dominated by tech bros and other affluent whites implies that it must be harmful to everyone else—a claim made by alluding to some unspecified amalgamation of oppressed persons (women, people of color, or non-cis citizens) who are insufficiently represented. It is assumed but not really demonstrated that people within the latter demographics would be unreceptive or even damaged by Harris’ approach. But given the lack of actual concrete harms laid out in these critiques, it is not clear whether the critics are actually advocating for those groups or that the social-theoretical existence of harms to them is just a convenient trope to make a mainly academic argument seem as if it actually mattered. People’s prospects for living well in the digital age would be improved if technology scholars more often eschewed the deconstructive critique from nowhere. I think they should act instead as “thoughtful partisans.” By that I mean that they would acknowledge that their work is guided by a specific set of interests and values, ones that are in the benefit of particular groups. It is not an impartial application of social theory to suggest that “realness” and “naturalness” are empty categories that should be dispensed with. And a more open and honest admission of partisanship would at least force writers to be upfront with readers regarding what the benefits would actually be to dispensing with those categories and who exactly would enjoy them—besides digital enthusiasts and ecomodernists. If academics were expected to use their analysis to the clear benefit of nameable and actually existing groups of citizens, scholars might do fewer trite Foucauldian analyses and more often do the far more difficult task of concretely outlining how a more desirable world might be possible. “The life of the critic easy,” notes Anton Ego in the Pixar film Ratatouille. Actually having skin in the game and putting oneself and one’s proposals out in the world where they can be scrutinized is far more challenging. Academics should be pushed to clearly articulate exactly how it is the novel concepts, arguments, observations, and claims they spend so much time developing actually benefit human beings who don’t have access to Elsevier or who don't receive seasonal catalogs from Oxford University Press. Without them doing so, I cannot imagine academia having much of a role in helping ordinary people live better in the digital age. “Finally, from so little sleeping and so much reading, his brain dried up and he went completely out of his mind.” – Cervantes, Don Quixote Don Quixote is more than a tale of man who deludes himself into believing that he is knight in the age of chivalry but an allegory about abstract knowledge and its dangers. Sleeping too little and reading too much, the man from La Mancha has much in common with the average graduate student in the social sciences or humanities. At the same time, I think that graduate students risk suffering a fate like Quixote's. Being in the midst of reading thousands of pages of social scientific research and philosophical argument for my dissertation’s literature review, quixotism is a danger never far from my mind.

The information and knowledge written down in books, of course, are sought in the hope that they will not only inform but also heighten one’s sensitivity to aspects of reality that could otherwise be overlooked. Having poured over a text about how community exists as a symbolic construction, for instance, I am encouraged to look beyond social structure when examining communities in the real world. Yet, immersing oneself in abstract knowledge also carries the risk inhibiting one’s ability to accurately interpret the world. The researcher may come to construct an imagined reality, built out of what they have read, that inaccurately colors their every observation of the world and even begins to merge with their own identity. The stereotype of the out-of-touch academic is, unfortunately, often used by people who would rather remain ignorant or find scholarly arguments incompatible with their ideology. Nevertheless, it is not a stereotype without a hint of truth to it. Interactions with classmates in seminar and colleagues at conferences have taught me that even the most sophisticated of thinkers build vast edifices to shore up beliefs that they take as unquestioned and axiomatic. What has struck me the most upon enrolling as a graduate student in science and technology studies is how many of my classmates discuss contemporary inequalities and injustices mainly in terms of reified abstractions. That is, such problems are caused by “the corrupt system” or “capitalism” writ large rather than some clear and nameable way that institutions and rules are designed; their theoretical concepts cease to elucidate reality but instead replace it. The whole of western modernity becomes suspect and, therefore, they leave themselves with little means of accomplishing positive change. How can one fight an enemy when it has become as abstract and as large as civilization itself? Similarly, I have interacted with a number of scholars, typically with strong libertarian or anarchist leanings, who cannot forthrightly admit negative consequences of Internet and other contemporary communication devices on people’s lives, communities and relationships. For instance, they write off those who view such devices as too easily affording narcissism or other forms of anti-social behavior, such as using cell phones to construct elaborate barriers to intimacy with others. I suspect that these scholars lack criticality concerning the Internet because its decentralized structure parallels the ideal politically decentralized world in which such scholars would want to live. In a similar way to how Don Quixote imagines a simple barber’s basin to be Mambrino’s famous helmet, the Internet becomes imagined mainly in terms of its abstract potential rather than as the pedestrian and uninspiring thing it is. It becomes an object confused with the theoretical construct to which it only bears a resemblance. Likewise, I am bothered by what I see as an odd degree of attention paid towards misogynistic jokes by comedians such as Daniel Tosh as driving “rape culture.” As distasteful to some as rape jokes may be, adult comedy is generally far removed from the actual processes of socialization that permit men to believe that they are entitled to take advantage of women; jokes are more likely a symptom of rape culture or a minor variable at best, hardly reason to dedicate so much energy towards it. Writers on Jezebel and other academically-rooted blogs, I fear, are like Don Quixote, tilting at windmills while believing they are attacking evil and menacing giants. Those who disagree with such writers are often viewed in such a way that the original crusade is further justified; the unwillingness of others to view the words of comedians as such a large item of concern becomes interpreted as a sign that rape culture and comedy are even further intertwined and entrenched than previously thought and gives justification for such writers to become increasing militant about joke telling[1]. In contrast, one of the most insightful blog posts I have read about the roots of rape culture is by someone who is not an academic “culture warrior” but instead simply takes note of how little boys are often allowed to behave in socially pathological ways toward little girls under the guise of "boys will be boys." This simple, everyday observation can be easily overlooked if one's view of the world is constituted only by that which can be described via abstract cultural analysis, having no role for developmental psychology. Preventing Don Quixote from realizing that the world he believes in is not like the one he interacts with is the sophistication with which he is able to construct ad hoc theorizations to shore up his worldview, in spite of evidence to the contrary. Each defeat and beating is reinterpreted through Quixote’s vast theoretical knowledge of chivalry so that his own world view is reinforced rather than undermined. It is fairly well-known in the psychological literature that most people’s attitude toward evidence contrary to their own ideologies are more like Don Quixote’s ad-hoc rationalizations than they care to admit, even among those who consider themselves “objective” or “rational.” It is not being like the Man of La Mancha that takes genuine effort; cognitive limitations are a constant presence in human thinking. Academics, in my experience, are often more adept than the average person at such theorizing away of inconvenient arguments and observations. As bothered as I am by the quixotic tendencies in my fellow academics, the possibility of suffering from a similar but unrecognized affliction concerns me the most. It is, of course, far easier to recognize sins of others than those perpetrated by oneself. What are the windmills and barbers’ basins in my own thinking? I worry that too often academic training provides students with a greater repository of tools for protecting their worldview from careful self-scrutiny as much as methods for asking critical questions about the world. The quixotism of an academic is perhaps even more dangerous than the average person’s self-imposed ignorances; university trained scholars are more likely to be utterly convinced of their own rationality. Nevertheless, as I continue to read too much and sleep far too little, I hope my own mind remains more flexible and self-critical than Don Quixote’s. [1] To be absolutely clear, I am not defending Daniel Tosh. Rather, my problem is that too much attention is paid towards such highly visible and most obviously outrageous incidents with little concern about whether or not expressing moral outrage at comedians gets contemporary civilization anywhere closer to discouraging rape. I believe that far too many cultural critics are more concerned with taking down public figures and celebrities for their failings and/or pathologies than being effective at rooting out the behaviors and mindsets that they oppose. |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed