|

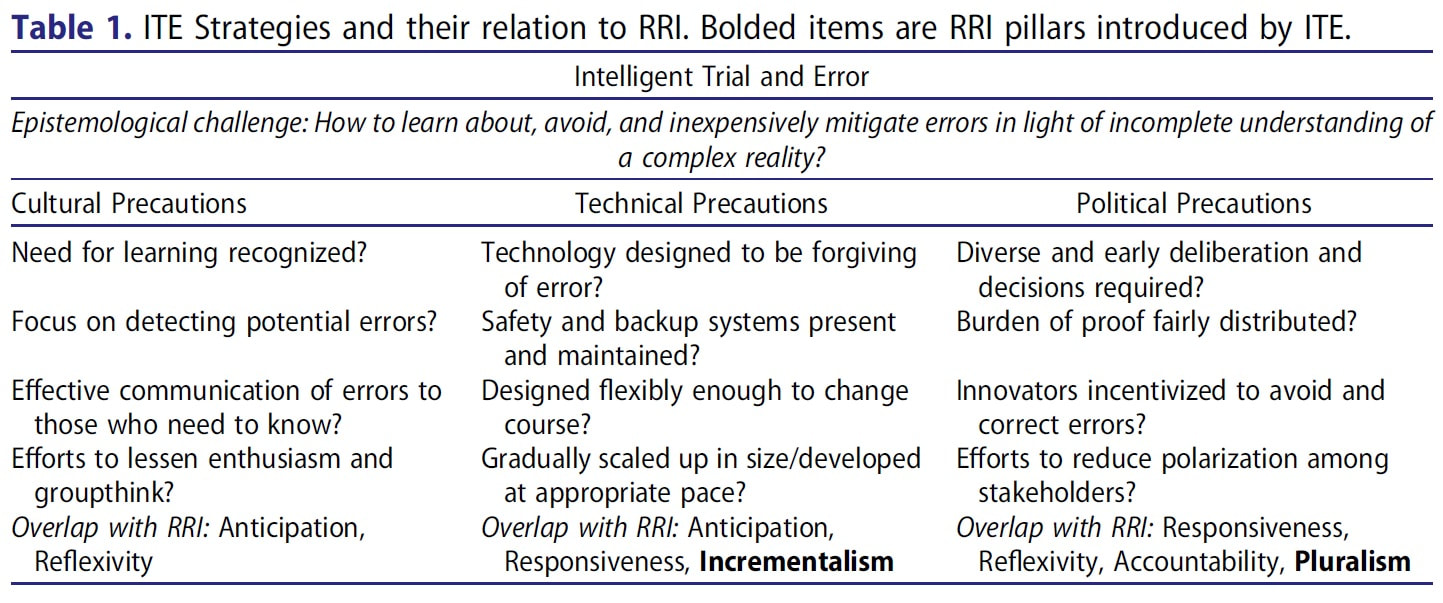

This is a more academic piece of writing than I usually post, but I want to help make a theory so central to my thinking more accessible. This is an except from a paper that I had published in The Journal of Responsible Innovation a few years ago. If you find this intriguing, Intelligent Trial and Error (ITE) also showed up in an article that I wrote for The New Atlantis last year. The Intelligent Steering of Technoscience ITE is a framework for betting understanding and managing the risks of innovation, largely developed via detailed studies of cases of both technological error and instances when catastrophe had been fortuitously averted (see Morone and Woodhouse 1986; Collingridge 1992). Early ITE research focused on mistakes made in developing large-scale technologies like nuclear energy and the United States’ space shuttle program. More recently, scholars have extended the framework in order to explain partially man-made disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans (Woodhouse 2007), as well as more mundane and slow moving tragedies, like the seemingly inexorable momentum of sprawling suburban development (Dotson 2016). Although similar to high-reliability theory (Sagan 1993), an organizational model that tries to explain why accidents are so rare on aircraft carriers and among American air traffic controllers, ITE has a distinct lineage. The framework’s roots lie in political incrementalism (Lindblom 1959; Woodhouse and Collingridge 1993; Genus 2000). Incrementalism begins with a recognition of the limits of analytical rationality. Because analysts lack the necessary knowledge to predict the results of a policy change and are handicapped by biases, their own partisanship, and other cognitive shortcomings, incrementalism posits that they should—and very often do—proceed in a gradual and decentralized fashion. Policy therefore evolves via mutual adjustment between partisan groups, an evolutionary process that can be stymied when some groups’ desires—namely business’—dominate decision making. In short, pluralist democracy outperforms technocratic politics. Consider how elite decision makers in pre-Katrina New Orleans eschewed adequate precautions, having come to see flooding risks as acceptable or less important than supporting the construction industry; encouraging and enabling myriad constituent groups to advocate for their own interests in the matter would have provoked deliberations more likely to have led to preventative action (see Woodhouse 2007). In any case, later political scientists and decision theorists extended incrementalism to technological development (Collingridge 1980; Morone and Woodhouse 1986). ITE also differs from technology assessment, though both seek to avoid undesirable unintended consequences (see Genus 2000). Again, ITE is founded on a skepticism of analysis: the ramifications of complex technologies are highly unpredictable. Consequences often only become clear once a sociotechnical system has already become entrenched (Collingridge 1980). Hence, formal analytical risk assessments are insufficient. Lacking complete understanding, participants should not try to predict the future but instead strategize to lessen their ignorance. Of course, analysis still helps. Indeed, ITE research suggests that technologies and organizations with certain characteristics hinder the learning process necessary to minimize errors, characteristics that preliminary assessments can uncover. Expositions of ITE vary (cf. Woodhouse 2013; Collingridge 1992; Dotson 2017); nevertheless, all emphasize meeting the epistemological challenge of technological change: can learning happen quickly and without high costs? The failure to face up to this challenge not only leads to major mistakes for emerging technologies but can also stymie innovation in already established areas. The ills associated with suburban sprawl persists, for instance, because most learning happens far too late (Dotson 2016). Can developers be blamed for staying the course when innovation “errors” are learned about only after large swaths of houses have already been built? Regardless, meeting this central epistemological challenge requires employing three interrelated kinds of precautionary strategies. The first set of precautions are cultural. Are participants and organizations and prepared to learn? Is feedback produced early enough and development appropriately paced so that participants can feasibly change course? Does adequate monitoring by the appropriate experts occur? Is that feedback effectively communicated to those affected and those who decide? Such ITE strategies were applied by early biotechnologists at the Asilomar Conference: They put a moratorium on the riskiest genetic engineering experiments until more testing could be done, proceeding gradually as risks became better understood, and communicating the results broadly (Morone and Woodhouse 1986). In contrast, large-scale technological mistakes—from nuclear energy to irrigation dams in developing nations—tend to occur because they are developed and deployed by a group of true believers who fail to fathom that they could be wrong (Collingridge 1992).

Another set of strategies entail technical precautions. Even if participants are disposed to emphasize and respond to learning, does the technology’s design enable precaution? Sociotechnical systems can be made forgiving of unanticipated occurrences by ensuring wide margins for error, including built-in redundancies and backup systems, and giving preference to designs that are flexible or easily altered. The designers of the 20th century nuclear industry pursued the first two strategies but not the third. Their single-minded pursuit of economies of scale combined with the technology’s capital intensiveness all but locked-in the light water reactor design prior to a full appreciation of its inherent safety limitations (Morone and Woodhouse 1989). No doubt the technical facet of ITE intersects with its cultural dimensions: a prevailing bias toward a rapid pace of innovation can create technological inflexibility just as well as overly capital-intensive or imprudently scaled technical designs (cf. Collingridge 1992; Woodhouse 2016). Finally, there are political precautions. Do existing regulations, incentives, deliberative forums, and other political creations push participants toward more precautionary dispositions and technologies? Innovators may not be aware of the full range of risks or their own ignorance if deliberation is insufficiently diverse. AIDs sufferers, for instance, understood their own communities’ needs and health practices far better than medical researchers (Epstein 1996). Their exclusion slowed the development of appropriate treatment options and research. Moreover, technologies are less likely to be flexibly designed if deliberation on potential risks occurs too late in the innovation process. Finally, do regulations protect against widely shared conflicts of interest, encourage error correction, and enforce a fair distribution of the burden of proof? Regulatory approaches that demand “sound science” prior to regulation put the least empowered participants (i.e., victims) in the position of having to convincingly demonstrate their case and fail to incentivize innovators to avoid mistakes. In contrast, making innovators pay into victim’s funds until harm is disproven would encourage precaution by introducing a monetary incentive to prevent errors (Woodhouse 2013, 79). Indeed, mining companies already have to post remediation bonds to ensure that funds exist to clean up after valuable minerals and metals have been unearthed. To these political precautions, I would add the need for deliberative activities to build social capital (see Fleck 2016). Indeed, those studying commons tragedies and environmental management have outlined how establishing trust and a vision of some kind of common future—often through more informal modes of communication—are essential for well-functioning forms of collective governance (Ostrom 1990; Temby et al. 2017). Deliberations are unlikely to lead to precautionary action and productively working through value disagreements if proceedings are overly antagonistic or polarized. The ITE framework has a lot of similarities to Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) but differs in a number of important ways. RRI’s four pillars of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten 2013) are reflected in ITE’s focus on learning. Innovators must be pushed to anticipate that mistakes will happen, encouraged to reflect upon appropriate ameliorative action, and made to include and be accountable to potential victims. ITE can also be seen as sharing RRI’s connection to deliberative democratic traditions and the precautionary principle (see Reber 2018). ITE differs, however, in terms of scope and approach. Indeed, others have pointed out that the RRI framework could better account for the material barriers and costs and prevailing power structures that can prevent well-meaning innovators from innovating responsibly (De Hoop, Pols and Romijn 2016). ITE’s focus on ensuring technological flexibility, countering conflicts of interest, and fostering diversity in decision-making power and fairness in the burden of proof exactly addresses those limitations. Finally, ITE emphasizes political pluralism, in contrast to RRI’s foregrounding of ethical reflexivity. Innovators need not be ethically circumspect about their innovations provided that they are incentivized or otherwise encouraged by political opponents to act as if they were. An op-ed that I wrote with Nicholas Tampio was published in the Washington Post on Saturday. The reaction was much stronger than I anticipated it would be. I was ready for the run-of-the-mill social media negativity that I see on Twitter everyday, but the vitriol in the article's comments and in Twitter replies was really something else. One person came to my wall to write that I had "blood on my hands", and no shortage of people questioned my intelligence and moral compass. In our article, Nick and I don't exactly come out against mandates writ large (though some have interpreted it that way), but that pursuing vaccine mandates right now will not be worth the costs. The thing to remember is that we're living through two pandemics at the moment: COVID and rampant political polarization. Getting vaccine numbers up faster while only making our democracy even more pathological is not a wise move. Things weren't helped by Tom Nicholas retweeting it to his 500k followers with such authoritative pronouncements as "It [vaccine mandates] is *exactly* how things work in a democracy, which is why you didn't get polio." For a guy who pronounced the "Death of Expertise," you'd think Nichols would pause to consider that maybe he might want to learn from people who study vaccine hesitancy and resistance before claiming to know what's best, but he hasn't. Nichols, like many people today who decry the declining respect for truth or democracy, is really taking issue with the reality that people think differently than him rather than that they don't respect expertise or act democratically per se. And that's exactly the problem that, as I argue in my book The Divide, underlies contemporary democracies. It's not so much that people are "irrational," but that political opponents are absolutely convinced that they are on the right side of truth, whether they are pro-vaccine or anti-vaxx. This fanatical certitude produces demand for fanatical policy. Just look at Max Boot's now deleted tweet praising vaccine mandates in the notably undemocratic Saudi Arabia, or Matthew Yglesias's suggestion that vaccine resisters should be given the jab by force. A lot of leftists and centrists are just as anti-democratic in their thinking as reactionary conservatives. It's just that that attitude only comes out when there's a population of citizens that refuse to embrace a truth that is accepted by the political mainstream. It's in these moments that self-described liberals and centrists out themselves as technocrats and agitate against the fundamental features of democracy: dialogue, negotiation, and compromise.

But they're not alone. As I demonstrate in my book, plenty of otherwise intelligent people have been confusing democracy with The Truth for quite some time, and that explains a lot of the political gridlock and intransigence in modern democracies. The question will be whether enough of us can rise to the challenge of democratic citizenship in the near term in order to avoid the "death spiral" of polarization that previously infected nations like Venezuela, pre-Pinochet Chile, and pre-Franco Spain. Using mandates as a stick to punish the unvaccinated, especially while also giving the appearance that it's motivated by partisanship, will make a polarization death spiral in this country a real possibility. **** But that's not the only thing that I've noticed in the reaction to the piece. First, many vaccine mandate advocates are unsurprisingly similar to the vaccine hesitant citizens in how they perceive risk. It's just in the opposite direction. One commenter described being worried everyday about her 3 year old ending up in the ICU with COVID. That's certainly a possibility, but the risk to children is actually not much more than it has been for other long-prevalent viruses like the flu and RSV. It's common to chide the vaccine hesitant for their "irrational fear" of vaccine side-effects, but plenty of vaccine supporters have a similarly outsized worries about COVID. Both should be considered "legitimate" concerns that we ought to take seriously, even if the goal is to eventually lessen the magnitude of those worries. The more annoying argument is the comparison between getting vaccinated and driving drunk: We don't let people onto public roads while drunk, why should we let the "reckless" unvaccinated into public spaces. This is a terrible metaphor. No one comes into the world drunk or driving the automobile, but we were all born without immunity to COVID. A person has to explicitly imbibe alcohol to become a drunk driver, while not being a COVID spreader (well, less of one) means permitting someone to inject a vaccine into your body. The metaphor completely blinds us to all of the important differences in these cases, making it easier to ignore the immense amount of trust in doctors, the FDA, and the pharmaceutical industry that it takes to get vaccinated. Plus, it reduces human beings to being disease-ridden virus vectors, which is somewhat dehumanizing. I think it's better to think of herd immunity as like an airplane, except it's an enormous plane that some 80 percent of us have to board before it can take off. People fear flying. They have to give up control. They have to trust the pilot, the FAA, and that engineers at companies like Boeing are all doing their jobs diligently. Would we strap people into their seats in that case or talk to them to try to alleviate their fears? Other thing that I've learned from some of the emails that I've received is that there's a big overlap between "essential workers" and the vaccine hesitant. At my own college and others throughout the country, it is staff and not faculty who are shunning the vaccine. At hospitals, it is nurses and orderlies who more often refuse, not doctors. Those of us who have been relatively shielded from most of the harms of COVID are often the ones most ardent in calling for mandates. A reader who emailed me framed it as "The professional class took none of the risks during the pandemic and are now forcing an experimental vaccine on us." That's a perspective that I hadn't considered, and it's one that I'm still thinking about. I think it explains some of the class dynamics of vaccine mistrust. One final realization that I've had concerns vaccines as technological fixes. Dan Sarewitz wrote that he thought they were the best example of using a technology to sidestep the social complexities and difficulties in solving a tenacious public problems. I now think that he's wrong. The techno-fix for disease like COVID-19 is treatment, not vaccine. This should be obvious, given how many of the vaccine hesitant have latched onto to uncertain treatments like Invermectin. Vaccines, like I noted above, require immense amounts of trust. They also ask that people who are not currently sick take a form of medicine. Treatments don't. People who are exceptionally sick see risks differently. They're looking to get better, not avoid getting sick. In light of the fact that pandemics aren't going to disappear anytime soon, we may want to put as much R&D into improving treatment options as into developing vaccines. We would be better off having a techno-fix that lets us temporarily sidestep the messy problem of vaccine hesitancy, giving us more time to engage with the vaccine hesitant, to hear their concerns, and build trust. In his review of Elizabeth Kolbert’s latest book, Ted Nordhaus chides humanity for being too “bashful” when it comes to manipulating nature, insisting that such manipulation is necessary if we are to meet our environmental protection aspirations. We’ve likely been in a kind of Anthropocene for far longer than we recognize. The cat is out of the bag, Nordhaus seems to be saying, so we might as well learn to embrace environmental tinkering in earnest. Yet for all his chiding of environmental activists and their “grossly simplified models of the relationship between humans and nature,” Nordhaus ends up offering an equally facile binary in its place.

Nordhaus is no doubt correct that the concept of nature has always been problematically slippery. Metaphors like “carry capacity”, “balanced webs”, and “great chain of being,” obscure as much as they enlighten. He reiterates the well-known problem with “nature.” That is, it is very difficult to draw the line where humanity ends and nature begins. Humans impacted the climate as soon as they discovered fire, a tool that they used to reshape their environment. Yet, despite William Cronon’s over 25-year-old critique of the fantasy of pristine wilderness and how it blinds people to the difficulties of our unavoidable interconnectedness to nature, the myth of the untouched environment persists. But humans think metaphorically. No differently from the problematic categorizations people use to order their world, they are a largely inescapable component of our imaginations. Eliminating previous metaphors and categorizations usually doesn’t uncover a previously hidden objective reality, because that process of elimination invariably involves overlaying new value-laden images on top of it. What exactly is the metaphor driving Nordhaus? It would have been nice if Nordhaus had been more explicit. I feel like he hid behind the truism that humanity’s tinkering with the environment has been ever present. But it’s not too difficult to read between the lines when he seems to put prehistoric humans creating grasslands where forests once stood at the same level as genetically engineering coral to survive anthropogenic climate change. Michael Shellenberger, only formerly associated with Nordhaus’ Breakthrough Institute, isn’t so keen to hide his cards. In coming out against renewable energy, he claims that their problem is that they cannot be sufficiently “modern.” Shellenberger makes a little bit too much out of a few Heidegger and Bookchin quotes and a handful of decontextualized statistics to claim that a society based on renewable energy would be inevitably arrested in a state of agrarian backwardness. Although Nordhaus isn’t so brazen, he doesn’t seem too different from Shellenberger when he talks of humanity’s relationship with the environment. In contrast to Shellenberger, however, he does recognize the risks, something apparent when he recounts the compounding unintended consequences brought on by creation of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. The canal was first constructed to keep Chicago’s sewage from inundating Lake Michigan. Asian carp was introduced to control weed and algae growth, but the carp’s capacious growth now threatens the ecosystem—only being reined in by erecting electric barriers to limit the species’ movement. As lamentable as this turn of events might be, Nordhaus waves it off: “Most Chicagoans would probably choose [ecological tragedy] over open sewers running through their streets.” Imagine that humanity’s control over their tinkering with the environment were regulated by the same controls in an automobile. Nordhaus and Shellenberger seem to be preoccupied with the accelerator and brake. The above depiction of the Chicago Sanitary Canal ends up implying almost the same Hobson’s choice as Shellenberger presents for renewable energy: We either dig canals and electrify them, following previous technological errors with new technical fixes in the same style, or we wallow impoverished and in shit. To fair, technological decisions don’t happen in a vacuum. They are path-dependent. We are partly ruled over by earlier decisions made by people who are now long dead. Electric (and perhaps automated) vehicles appear to be the only answer to the ills of the automobile in a country where travel by foot, bicycle, or trolley car is made difficult to impossible by already established infrastructure—not to mention culturally entrenched ideas connecting automobility to progress, America, and masculinity. But the answer given by eco-modernists, even if more implied than explicitly stated like in Nordhaus’s book reviews, reads almost like a kind of learned helplessness in the face of "progress": “This is the path we’re on, we might as well stick with where the least resistance seems to be. But don’t worry! We have read the statistical tea leaves. Everyone will probably be better off. We might as well push forward with our current mode of tinkering.” History may end up vindicating ecomodernists’ faith in linear progress, at least in the short term, but their quickness to discount alternative pathways stifles a more charitable conversation about environmental problems. There is a real and troubling tendency in ecomodernist writing to reduce the debate into a black-and-white struggle between cornucopians and Malthusians, modernity and pre-modernity, or abundance and austerity. Such a move is just as oversimplifying as the “pristine nature” myths they critique. Notions like modernity, progress, and abundance are themselves inextricably value-laden. If there is anything productive to come out of debates about how humanity ought to tinker with nature it will only be if those debaters were more honestly up-front about their value commitments. Too often ecomodernism (or degrowth) is presented similarly as liberalism, as if it were just a neutral path toward a better world rather than a one particular partisan vision of the good. And too often, statistical trends read from thirty thousand feet are included less to inspire thoughtfulness and more to lend one side’s argument an aura of inevitability: “Can’t you see that collapse/progress is coming?” Obscured are deeper questions about what makes for a good life and a good society. Exactly what kind of world should our environmental tinkering lead to? Just because words like “nature” can be problematic social constructions doesn’t mean that they are useless. Most people would admit that there is a significant difference between viewing a tiger at the zoo and encountering one in a jungle. All the thorniness inherent in the concept of wilderness aside, dispensing with the notion that non-human or “natural” agency is important prevents a more complex conversation regarding biological and environmental problems, one that can’t be reduced to facile questions like “Is energy use good or bad?” Consider minimalistic shoes, of which Vibram’s FiveFinger shoes are only one example. These shoes are touted for helping runners realize a more “natural” running form, biomechanics ostensibly discouraged by the heavily padded runners developed during the 20th century. The debates regarding the merits of the shoes quickly went into scientistic territory, with no shortage of evidence available for either side to declare victory. But most observers missed that the central tension was only superficially about what constitutes a “natural” human gait. It was really rooted in the question of how people should interact with the very ground that they run on. Are the parts of nature outside of our own bodies something simply to insulate and protect against or should there be a more dynamic dance between the agencies of non-human nature and of people? Should our shoes be built to make the material configuration of the ground almost irrelevant to our running or keep it as something we are forced to reckon with on an intimate level? Taking these examples seriously doesn’t mean falling back upon an idealized bucolic nature, one without the “corrupting” influence of human beings and their technologies. Rather, the point is that there are different qualitative styles to engaging with world that the exists outside people and their creations. A pair Vibrams is no less a technological creation than Nike’s Vapormax running shoes, but each take for granted a different relationship to inherited human biology and how it intersects with the ground. Our disagreements about nature will only be productive when we recognize that it is the tension (and fuzzy border) between nature-to-be-controlled and nature-to-be-engaged, not fanaticizing binaries like “abundance vs austerity,” that lies at the root of them. It’s easy to forget that Chicago only needed a Sanitary Canal because American society chose to dump its waste into waterways rather than compost it. Chicagoans were wallowing in shit because they failed to envision a relationship with waste other than trying to make it disappear into ditches, sewers, and lakes. Because they failed to commune with composting bacteria, early modern cities had to go to war with cholera. We lose the ability to reimagine the dynamics and character of humanity’s tinkering with nature when progress is imagined as a binary. The pathways available to us are not just forward and backwards, toward “modernity” and away from it, or doing things “because we can” and environmental asceticism. There is a steering wheel available to human societies, which they could use to chart any number of pathways through our environmental challenges, if we would only remember that it’s there. How can STS scholars spread their work and ideas outside of academia? In the last decade, STS has demonstrated a broad commitment to extending the rails of its scholarship. Yet even well-meaning tech activists like Tristan Harris and Cathy O’Neil have seemed unaware of even the existence of the field, much less the contributions it could make to public debates. And when STS scholarship does appear in popular works, such as in Planet of the Humans, things sometimes go off the rails. But the interdiscipline has immense potential to help with impending crises, such as climate change or “post-truth” politics. At the very least, it is imprudent to allow scientistic narratives proffered by people like Michael Shellenberger or techno-fixes proposed by Mark Zuckerberg to dominate the media.

The purpose of this panel is to share knowledge and collaborate in imagining how STS trained people could be more effective “thoughtful partisans,” how their research and analysis could more reliably influence policy debates. We are interested in panelists who can speak to: How to pitch STS-inspired op-eds to popular outlets? How to reach out to and work with journalists and documentary filmmakers? How to run a successful podcast or YouTube channel? Participants should be open to non-traditional panel formats, ones that allow more interaction and sharing with attendees. And we are particularly interested in contributions that emphasize learning from non-academics (not simply “informing” them) as well as engaging diverse audiences, especially across race, class, level of education, and political affiliation. Panel Organizers Taylor Dotson, New Mexico Tech Michael Bouchey, New Mexico Tech Society for Social Studies of Science Toronto and World-wide, October 6-9, 2021 Submissions will open Monday, January 25 Deadline: March 8th, 2021 (Link) Although it is a common cliché that a new sitting president will “unite” us, the idea of the “American people” falling in line behind a new administration is a fantasy. Presidential approval ratings have always been polarized along party lines—although the partisan gap has widened over the decades. Yet such rhetoric remains an integral part of the post-election political theater, helpful for relieving some of the partisan pressure built up over a frequently nasty campaign season.

The gaping chasm between Biden supporters and Trump voters, however, is not going to be narrowed by rhetorical olive branches. The pre-election belief that ousting Trump would restore political normalcy is rooted in the mistaken idea that his 2016 success was an aberration, a freak anomaly that would be soon forgotten after a more respectable statesman or woman took over the Oval Office. That story is nothing more than a flight of fancy, one that ignores the underlying causes for rampant polarization, “post-truth,” Trumpism, or however one diagnoses our political malaise. The problem is that Americans worship entirely different notions of Truth. Trumpist Heresy Many of my fellow leftist friends and colleagues desperately want to believe that Trumpism is little more than the last gasps of a dying racist culture. It is a convenient move, which allows them to think of Trump voters as the political equivalent of anti-vaxxers. Once diagnosed as hopelessly deluded and on the wrong side of history, there is no longer any need to understand Trump voters. They only need to be defeated. Washington Monthly contributor David Atkins openly wondered how we could “deprogram” the 75 million or so people who voted for Trump, dismissing their electoral choice as due to belonging to “a conspiracy theory fueled belligerent death cult against reality & basic decency.” What a way to talk about an almost full quarter of the population! Only the most dyspeptic will admit to daydreaming about ideological reeducation drives, at least publicly. Optimists, on the other hand, allow themselves to believe that “truth and rationality” will inevitably win out, that the wave of popular support for politicians like Trump will naturally subside, ebbing away like the tide. The desire to equate of Trumpism with white supremacy is understandable, even if it is probably political escapism. Trump’s company faced a 1973 federal lawsuit for racial discriminating against black tenants, and he took out a full-page ad in the New York Times in 1989 to call for the death of five black and Latino youth falsely accused of sexually assaulting a white jogger. His 2016 campaign rhetoric included insinuating that Mexican immigrants mostly brought drugs and crime to the United States, and promised tough-on-crime legislation that disproportionately burdens minority neighborhoods. The “dying racist America” thesis is not merely propped up by a sober accounting of Trump’s panoply of racial misdeeds but by attacking the next plausible explanation: working class discontent. Adam Serwer’s review of the 2016 election statistics raises serious challenges to that argument. Clinton won a greater proportion of voters making less than $50,000. And neither did the opioid epidemic ripping through white rural America seem to tip the election toward Trump. White working-class citizens whose loved ones were coping with mental health problems, financial troubles, and substance abuse expressed less support for Trump, not more. But then again Biden was most successful in the counties where the bulk of America’s economic activity occur. The 477 counties accounting for 70 percent of the US economy went to the former vice-president, while a greater proportion of counties that have faced weak job, population, and economic growth went to Trump. To top it off, Trump lost white votes in 2020 and made significant, albeit single-digit, gains among African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans. Although Trump’s base has traditionally been with white voters who railed against immigration and the perceived feminization of society, neither the “economically disenfranchised working class” nor the “white supremacy” theses seem to really explain the former president’s appeal. Science vs. Common Sense Political movements are rarely understood by focusing on members’ deficiencies. An especially misleading starting point is wherever those movements’ opponents think the deficits are. Political allies are more strongly bonded by their shared strengths than their flaws—however obvious and fatal the latter may be. Data on the employment backgrounds of political donations are insightful here. The Democrats are increasingly of not just the party of the professional class, but the college-educated in general. Scientists, engineers, lawyers, teachers, and accountants dominated donations to Biden, whereas Trump’s support came from business owners, police officers, truckers, construction workers, pilots, stay-at-home mothers, and farmers. This split doesn’t map well onto to income-based conceptions of “working class.” Business owners and pilots often make a good living for their families, while well-educated social workers do not. Rather, the difference lies in which kind of knowledge defines their competency. Today’s political divisions are only indirectly class and racially based, the more fundament divide is between formally schooled expertise and experience-based judgment. Office workers, service employees, and elite knowledge-sector analysts are on one side, whereas blue-collar manual laborers and business owners are on the other. Despite our culture’s tendency to equate intelligence with a talent for mathematical abstraction or the patience (or pretension) to read dense books by French authors, writers like Mike Rose and Matthew Crawford remind us of the discerning judgements necessary for competence in physical work. Blue collar workers and business owners don’t explicitly analyze symbols but have precisely tuned gut feelings that help them do their jobs well. Much of America’s political malaise is due to the polarized veneration of these competing styles of knowledge. The idolization of science translates into support for technocracy, or rule by experts. The same worship but for common sense drives an attraction to populism. It is this division above all others that increasingly separates Democrats and Republicans. In his victory speech, Biden explicitly painted himself as a defender of science, promising to put properly credentialed experts in charge of pandemic planning. In contrast, Trump and his allies have taken great lengths to champion how (some) lay people (fail to) understand public problems. Recall how Newt Gingrich dismissed FBI crime statistics as immaterial in the run-up to the 2016 election, stating that “the average American…does not think that crime is down.” He followed up with, “As a political candidate, I’ll go with what people feel.” Likewise, faced with polls and election numbers showing a Biden victory, Trump voters saw the occurrence of voter fraud as “common sense.” They reason that since Democratic politicians and media outlets despise Trump so much, why wouldn’t they collude with poll workers to spoil the election? As Democrats have portrayed themselves as defending “the facts,” the right has doubled down on gut feeling. This same dynamic increasingly defines America’s racial politics as well. Armed with concepts and theories from academics such as Robin D’Angelo, people don’t end up having rich, empathy-evoking conversations about their experiences of race in America. Rather, the more militant members of the “woke” left play armchair psychologist, focusing on diagnosing fellow citizens’ racist personality dysfunctions and prescribing the appropriate therapeutic interventions. They demand that others learn to understand their lives through the vocabulary of critical race scholars, whose conclusions are presented as indisputable. White people who struggle with some critical race theorists’ stark view that one is either racist or actively anti-racist are labeled as suffering from “white fragility,” an irrational and emotional response to having one’s own undeniable racism exposed. Regardless of whether one thinks this judgement is apt or not, it is difficult to deny that the prognosis comes off as arrogant and dismissive. How else would we expect participants to respond when hearing that some of their cherished ideas about valuing hard work, individualism, or the nuclear family is just part of an inherently racist “white culture”? But empathic understanding is often in short supply when antiracists find themselves in a rare teachable moment. As a New York City Education Councilwoman put it to her colleague in a now viral video, “Read a book. Read Ibram Kendi….It is not my job to educate you.” Many conservative Americans have reacted to the inroads that critical race theory has made into the workplace and popular discourse by retreating to a similarly incurious form of “common sense.” Ideas from critical race theory become labeled as political correctness run amok, or even “cult indoctrination.” All this is somehow imposed on the rest of the nation by left-wing academic activists whose far-reaching powers somehow only disappear when it comes to concretely influencing policymaking or to getting their 18-year-old students to actually read for class. Regardless of where one’s sympathies lie in this debate, it seems clear that productive conversations across party lines about the extent of America’s racial problems and what could be done about them are simply not happening. Absent-Minded Scientism The real tragedy of today’s political moment is that the elevation of “truth” over politics has locked us into a vicious cycle. Technocracy breeds popular distrust in experts. And the specter of populism spurs the professional class to further wrap themselves in the mantle of “the facts.” And no one budges on anything. Consider ongoing protests of pandemic protection measures. Resistance to state government’s social distancing and stay-at-home requirements has not been a rejection of science so much as the rejection of the inflexibility, strictness, and occasional arbitrariness of executive orders. Yet many governors have reacted to the pandemic situation as if politics is no longer necessary, as if leaving any room for negotiation were dangerous. California’s Gov. Gavin Newsom stated that “health outcomes and science – not politics” would guide reopening plans. And Michigan’s Gov. Gretchen Whitmer concurred, contending that her decision was a “data-driven approach based on facts, based on science, based on recommendations from experts.” And much of the media repeats ad nauseum the facts of the matter. It is as if journalists believe that if they present just the right infographic on ICU beds or presentation of the size of one’s social “bubble”—along with a healthy dollop of social shaming—less risk averse Americans will immediately change their holiday plans and social lives to sequester at home. When that fails to happen, the talking points shift to the irrationality and immorality of a public that fails to respect facts. The problem with the mantra “please just listen to the science!” is that science literacy doesn’t determine whether citizens listen or not. What matters is the perceived trustworthiness of experts and public officials. Expert guidance only gets legitimated through a kind of common sense. Citizens go “with their guts” on whether the elected officials and their science-based advice seems sensible and trustworthy. One of the best ways to inadvertently sow distrust in experts is to portray them as an unquestionable authority. Anywhere where “post-truth” seems to be on the upswing—in the response to the pandemic or for childhood vaccinations—the determinations of experts are handed down as if divinely decreed, or as if citizens’ reservations need to be only “managed” or countered. The stakes are judged to be so high that ordinary people are deemed unworthy of being consulted regarding how exactly expert recommendations should be implemented. Health researchers and doctors don’t think to ask the vaccine hesitant how they might be made to feel more comfortable with the vaccination process; state governors never bothered to ask people how pandemic protections might be implemented in ways that are less disruptive to their lives. The other way is for experts to get things wrong. When “the facts” are initially presented as unassailable, later corrections aren’t taken as the routine self-corrections of the scientific process but rather as evidence that the science has been tainted by politics. Early in the pandemic, health experts told the public that masks were ineffective at preventing a COVID-19 infection, but then turned around and recommended that they be mandatory in many states’ pandemic guidelines. The minor inconveniences of mask wearing and reduced restaurant occupancy have blown up to become perceived as gross violations of freedom in the “common sense” of a substantial portion of Americans not because those citizens deny science but rather because expert opinion was arrogantly applied. Officials failed to be honest and admit that even the scientists were feeling their way through an uncertain situation and that they too make value judgements in light of what they don’t yet understand. And governmental policies have been inconsistent and sometimes unfair. I can get ticketed in my own state if I walk around a deserted athletic field without a mask. In many states, bars and restaurants are open but outdoor playgrounds remain closed. It doesn’t take a scientist to know that these rules probably do not match the on-the-ground risks. But when leaders and experts overplay their hand, some portion of citizens just start taking expert guidance less seriously. Precious political capital is wasted to enforce compliance in ways that may be pure hygiene theater. Neither has it helped that governors such as Andrew Cuomo originally seemed content to waste vaccines, lest they go to someone who has been calculated by state bureaucrats to be less deserving. Beyond Political Road Rage Amidst the trench warfare between technocrats lobbying fact-laced truth bombs and populists laying “common sense” landmines, Americans have largely forgotten how to do politics. The underlying reasoning is understandable. If our collective problems are recast as completely solvable by straightforwardly applying science or something called common sense, what reason is there to debate, negotiate, or listen? Doing so would needlessly give ground to ignorant rubes and brainwashed ideologues. Americans need not like the viewpoints of their compatriots, but they ought to at least try to understand them. But far too many people appear to put their faith in Truth with a capital T. If only their opponents could be led to see the light and recognize “the facts” or popular “common sense” that they would they quit arguing and toe the line. If only politics were so simple. It is easy to imagine things getting much worse. A less dysfunctional public sphere feels like a utopian daydream. A good first step would be for Democrats to stop wrapping themselves in the mantle of science and learn to listen better to Americans who don’t have a college degree. Everywhere that populism has developed, it has been in reaction to the popular perception that the political establishment is increasingly elitist and distant. Is it any surprise that 64% of Americans now disagree with the idea that politicians “care what people like me think”? Appearing to hand important political decisions over to scientists in distant universities and governmental agencies is literally the worst thing that elected officials could do right now. For their part, conservatives, libertarians, and others should lay off the polarizing rhetoric about universities and experts. Rather than attack expertise itself, it is far better to focus instead on efforts to intellectually diversify higher education or turn political conversations back toward the moral (rather than factual) divides that define them. The claim that institutions of higher education are “under attack” by an “insidious” woke ideology is needlessly melodramatic. It reinforces the image of the world as hopeless divided between incommensurable worldviews and further fuels polarization between credentialed expertise and practical common sense. Worst of all, it portrays wokeness is something to be excised from the body politic rather than faced up to as a legitimate political adversary. Hyperbolic handwringing about traitorous cultural Marxists is as antidemocratic as any of the more draconian proposals coming from the left. Taking one’s political adversaries seriously means making a serious effort to persuade fence sitters—and not just through shaming. When a majority of Americans balked at the “Defund the Police” slogan over the summer, defenders doubled down on the phrase. The problem wasn’t with their poor choice of rhetoric, they seemed to imply, but that the public was misinformed about what the phrase really meant. I can’t think of a more potent example of willful political unawareness. Whether it is woke-ism or Trumpism, fanatical political movements tell us that something is seriously amiss in our body politic, that an area of public discontent is in a need of serious attention. We must be willing to take those discontents seriously. Focusing on apparent deficits in factual understanding or commonsense reasoning prevents us from better addressing the underlying causes of popular frustration. George Carlin once mused, “Have you ever noticed that anybody driving slower than you is an idiot and anyone going faster than you is a maniac?” American political discourse is little different, having become the rhetorical equivalent of road rage. Citizens need more productive ways to talk about their collective problems. Unless people are willing to admit that people can hold a different political viewpoint without being either an idiot of a maniac, there is little hope for American democracy. Power will just continue to vacillate between aloof technocrats and populist buffoons. Joseph Epstein's recent Wall Street Journal op-ed has been controversial to say the least. While his article is ostensibly penned as a personal letter to the future first lady, Jill Biden, urging her to not so adamantly insist on being called "Doctor", his main focus is on what he sees as the "watering down" of the academic doctorate.

Much of the fury directed at Epstein (and the Wall Street Journal for publishing it) has focused on signs that he was possibly more motivated by sexism than a good faith exploration of what honorific Doctor should mean. He doesn't help his case by being informal to the point of condescension. I mean, he referred to her as "kiddo"! Even though there is a more charitable interpretation: Epstein was playing off of future President Biden's own rhetorical style, that allusion was not clear to nearly all readers. Given both their of their ages and career experience, Jill Biden and Joseph Epstein are obviously peers. If Epstein had wanted more people to take him seriously, he would have avoided seeming to talk down to the future first lady. Put in context of the long hard road that women have had to fight to get themselves taken seriously within fields like academia, his approach is tone deaf, if not worse. I made the mistake on Twitter of trying to engage with the non-sexist part Epstein's thesis. (Yes, I am really that bad at social media). As unsavory as the history of women's credentials being disrespected is, I don't think we should let that history totally overshadow all the other readings of Epstein's argument. Certainly one can argue that discussing whether a PhD really merits being called Doctor should wait until our society is more equal. But that is different than the implication that the question is sexist on its face. Regardless, Epstein's focus is on the increasing ease with which PhDs can be obtained. Exams on Greek and Latin have been dispensed with. More and more PhDs are being minted every year. And honorary doctorates are seemingly handed out to anyone with a sizable donation to offer or even a middling level of celebrity. I think debating the "difficulty" of the degree is the wrong question. Any kind of credential could be made excessively arduous so as to weed out most of the students that attempt it. When I get introduced as Doctor, I usually qualify with a jokey line that my father-in-law used to add, "But not the kind that helps people." The sensibility at the heart of that joke is what lies at the crux of the issue. The extra respect that medical professionals receive is not simply due to the difficulty of obtaining a medical degree. Though, even in that line of thought, it is easy to forget that medical doctors have to take difficult licensing exams, pursue continuing education, and can face potential discipline by a professional governing body--things that PhDs are almost nowhere subject to. Rather, the most important difference between MDs and PhDs is that the former take the Hippocratic Oath. They publicly commit to using their knowledge to help others, although they can and sometimes do fall fall short of that aspiration. The beneficiaries of the work of PhDs are often unclear. The cliché that PhDs are motivated purely by curiosity or knowledge for knowledge's sake obscures a troubling reality. The most reliable benefits of academic work accrue to the researcher themselves (in terms of professional status) and to the small clique of scholars they associate with. No doubt there are exceptions, such as when PhDs admirably choose to work on "applied" problems. But those researchers usually take a big hit professionally by doing so. If PhDs are to earn the Doctor label they should be required to take an analogous oath, one that commits them to using scholarship to benefit at least some small group of people who do not hold PhDs. The attitude that PhDs are entitled to the status of Doctor because they successfully wrote a dissertation, in my mind, inevitably culminates in a narcissistic form of elitism. Status should be a product of how a person serves others, not something awarded because they survived a largely arbitrary academic gauntlet. One of the major oversights that Epstein made in his piece was that he failed to take seriously the difference between a PhD and the degree that Jill Biden actually has, an EdD. Educational doctorate programs are designed to enable graduates to apply their knowledge to situations that are likely to be encountered in real-life educational settings. It is a credential that sets up graduates to do good in the world, not just produce knowledge for other academics. So, in light of my own argument, Jill Biden is more befitting of the Doctor honorific than I am. That is a more exciting and interesting conclusion than I thought would have come from engaging with Epstein's sexist op-ed, one that is worth considering.

It seems hard to square face-to-face education with pandemic prevention. In states like Colorado, increasing COVID transmissions are driven by college student cases. The New York Times tallies 178 thousand infections and counting at institutions of higher learning across the country. My own institution has just shut down in-person classes for the next two weeks after learning about several large parties happening over the weekend. The few colleges that so far seem to be successful at preventing outbreaks have expended immense resources, some going so far as to test students weekly or prohibit leaving campus except for an emergency. Are universities up to the task of preventing pandemics?

So-called hybrid and in-person classes have taken an immense about of planning and preparation. Hand sanitizer and face masks had to be bought in immense quantities, rooms needed reconfigured for distance education, and dorms and food service needed redesigned to support social distancing. Unfortunately, it seems like few, if any, college administrators gave as much consideration to the organizational and social facets of pandemic prevention, preferring to wag their finger at undergraduates and expect them to behave. No one appears to have stopped to ask, “What do students need in order to be able to comply?” Just as abstinence-based sex education is ineffective at reducing teenage pregnancy, an abstinence-based approach to pandemic schooling won’t stop social intimacy among college students. And this should have been no mystery to college administrators, or at least it would not have been if they consulted social scientists rather than only epidemiologists and virologists. Safety has rarely been the technological accomplishment. Preventing outbreaks could have only be done through achieving the right kind of campus culture and a deep understanding of how to actually empower people to act safely. The reality that safety is socially accomplished is well-known to people who study risky technology. Decades of studies on operators of nuclear reactors, sailors on aircraft carriers, and air traffic controllers show that safety can be assured only by investing in a culture of high reliability. High reliability organizations invest considerable time and effort investing in people. Members need to have complete “buy in” regarding the organization’s performance. They not only receive considerable training but are also empowered to help make important collective decisions about the hazards they face. High reliability employees are more than just “rule followers.” The question is, “Can university campuses become high reliability organizations when it comes to pandemic prevention?” There is good reason to believe the answer is “no.” The same kinds of organizational studies that uncovered the existence of organizations capable of averting disaster typically found college bureaucracies to be very much the opposite. Festering problems go unaddressed, “solutions” are developed to non-existent problems, and decisions get made without obvious efforts at careful problem solving. The organizational dysfunction of universities is well known to the people that work in them. We have just been lucky up until now that colleges haven’t had to actually handle anything hazardous, like nuclear fuel or supersonic jets. The consequences of chronic institutional incompetence are just a growing mental health crisis among students, poor graduation rates, and graduates who lack many of the fundamental skills that they will actually need in their later careers. To the skeptic, the solution is dead simple: colleges should only offer online classes. That is the only inherently safe strategy. As a classic paper on the safety of petrochemical plants put it, “What you don’t have, can’t leak.” The easiest way to mitigate the harms of dangerous chemicals is to employ them in smaller amounts, move them shorter distances, introduce them into chemical reactions under more benign conditions, or simply replace them with safer alternatives. The same is true for colleges: What students you don’t have on campus, can’t get infected. But perhaps that goes too far. Maybe there are lessons from the safe operation of nuclear plants and other potentially catastrophic technologies that could be applied to the college environment. Safety expert Sidney Dekker calls one version of the high reliability approach “Safety Differently,” and it works by seeing people not as problem to managed or to fixed but rather as essential parts of the solution. University administrators have mainly done the former by implementing mandatory testing and quarantine procedures, enforcing social distancing protocols, and employing threats of punishment and injunctions to “be responsible” to try to cajole the students into doing the right thing. All those efforts seem commonsensical. The problem is that they backfire. Threats of punishment lead people to hide their mistakes, meaning that vital information is not shared with the people who need them. Students have a party, then lie about it. An overemphasis on protocols reduces safety to rule following, undercutting people’s motivation to think about what the right thing to do might be for a given situation. People treat mask wearing and 6 ft. of distance as if it were magic. They enforce compliance in situations where transmission risk is likely already low, like when walking outside, which can eat away at the seriousness that people take mask requirements. And it remains an open question whether or not cloth masks are really good enough to last an hour of breathing and talking in the enclosed space of a classroom, especially if students don’t launder them enough or they become wet. Making students part of the solution of pandemic prevention would mean including them in discussions about what kinds of protocols should be implemented and how. In the effort to prevent campus outbreaks, students are no longer universities’ “customers” and more like the operators of a nuclear reactor. It is their behavior that determines whether risks are contained. It is only students who can prevent a pandemic meltdown. Most importantly, they are the only ones with the expertise regarding how different demands and precautions can be made compatible with student life and their social and mental health needs. Without them, administrators are trying to manage a high-risk sociotechnical system that they can’t really understand. But that sounds like a tall order. Cultivating a high reliability culture is one thing on an aircraft carrier, but quite another among college students. Even worse, students are already infantilized by our educational system in general: by the demeaning carrot and stick incentives of the grading system; by the lack of space for individual curiosity; and by the reluctance to let students take responsibility for their own learning. If we cannot even trust students with their own education, how can we rely on them to be responsible when it comes to COVID? Achieving outbreak-free in-person campuses may prove to be impossible without far more radical changes to the structure of higher education.

Are Americans losing their grip on reality? It is difficult not to think so in light of the spread of QANON conspiracy theories, which posit that a deep-state ring of Satanic pedophiles is plotting against President Trump. A recent poll found that some 56% of Republican voters believe that at least some of the QANON conspiracy theory is true. But conspiratorial thinking has been on the rise for some time. One 2017 Atlantic article claimed that America had “lost its mind” in its growing acceptance of post-truth. Robert Harris has more recently argued that the world had moved into an “age of irrationality.” Legitimate politics is threatened by a rising tide of unreasonableness, or so we are told. But the urge to divide people in rational and irrational is the real threat to democracy. And the antidote is more inclusion, more democracy—no matter how outrageous the things our fellow citizens seem willing to believe.

Despite recent panic over the apparent upswing in political conspiracy thinking, salacious rumor and outright falsehoods has been an ever-present feature of politics. Today’s lurid and largely evidence-free theories about left-wing child abuse rings have plenty of historical analogues. Consider tales of Catherine the Great’s equestrian dalliances and claims that Marie Antoinette found lovers in both court servants and within her own family. Absurd stories about political elites seems to have been anything but rare. Some of my older relatives believed in the 1990s that the government was storing weapons and spare body parts underneath Denver International Airport in preparation for a war against common American citizens—and that was well before the Internet was a thing. There seems to be little disagreement that conspiratorial thinking threatens democracy. Allusions to Richard Hofstadter’s classic essay on the “paranoid style of American politics” have become cliché. Hofstadter’s targets included 1950s conservatives that saw Communist treachery around every corner, 1890s populists railing against the growing power of the financial class, and widespread worries about the machinations of the Illuminati. He diagnosed their politics paranoid in light of their shared belief that the world was being persecuted by a vast cabal of morally corrupt elites. Regardless of their specific claims, conspiracy theories’ harms come from their role in “disorienting” the public, leading citizens to have grossly divergent understandings of reality. And widespread conspiratorial thinking drives the delegitimation of traditional democratic institutions like the press and the electoral system. Journalists are seen as pushing “fake news.” The voting booths become “rigged.” Such developments are no doubt concerning, but we should think carefully about how we react to conspiracism. Too often the response is to endlessly lament the apparent end of rational thought and wonder aloud if democracy can survive while being gripped by a form of collective madness. But focusing on citizens' perceived cognitive deficiencies presents its own risks. Historian Ted Steinberg called this the “diagnostic style” of American political discourse, which transforms “opposition to the cultural mainstream into a form of mental illness.” The diagnostic style leads us to view QANONers, and increasingly political opponents in general, as not merely wrong but cognitively broken. They become the anti-vaxxers of politics. While QANON believers certainly seem to be deluding themselves, isn’t the tendency by leftists to blame Trump’s popular support on conservative’s faculty brains and an uneducated or uninformed populace equally delusional? The extent to which such cognitive deficiencies are actually at play is beside the point as far as democracy is concerned. You can’t fix stupid, as the well-worn saying has it. Diagnosing chronic mental lapses actually leaves us very few options for resolving conflicts. Even worse, it prevents an honest effort to understand and respond to the motivations of people with strange beliefs. Calling people idiots will only cause them to dig in further. Responses to the anti-vaxxer movement show as much. Financial penalties and other compulsory measures tend to only anger vaccine hesitant parents, leading them to more often refuse voluntary vaccines and become more committed in their opposition. But it does not take a social scientific study to know this. Who has ever changed their mind in response to the charge of stupidity or ignorance? Dismissing people with conspiratorial views blinds us to something important. While the claims themselves might be far-fetched, people often have legitimate reasons for believing them. African Americans, for instance, disproportionately believe conspiracy theories regarding the origin of HIV, such as that it was man-made in a laboratory or that the cure was being withheld, and are more hesitant of vaccines. But they also rate higher in distrust of medical institutions, often pointing to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and ongoing racial disparities as evidence. And from British sheepfarmers’ suspicion of state nuclear regulators in the aftermath of Chernobyl to mask skeptics’ current jeremiads against the CDC, governmental mistrust has often developed after officials’ overconfident claims about the risks turned out to be inaccurate. What might appear to an “irrational” rejection of the facts is often a rational response to a power structure that feels distant, unresponsive, and untrustworthy. The influence of psychologists has harmed more than it has helped in this regard. Carefully designed studies purport to show that believers in conspiracy theories lack the ability to think analytically or claim that they suffer from obscure cognitive biases like “hypersensitive agency detection.” Recent opinion pieces exaggerate the “illusory truth effect,” a phenomenon discovered in psych labs that repeated exposure to false messages leads to a relatively slight increase in the number subjects rating them as true or plausible. The smallness of this, albeit statistically significant, effect doesn’t stop commentators from presenting social media users as if they were passive dupes, who only need to be told about QANON so many times before they start believing it. Self-appointed champions of rationality have spared no effort to avoid thinking about the deeper explanations for conspiratorial thinking. Banging the drum over losses in rationality will not get us out of our present situation. Underneath our seeming inability to find more productive political pastures is a profound misunderstanding of what makes democracy work. Hand Wringing over “post-truth” or conspiratorial beliefs is founded on the idea that the point of politics is to establish and legislate truths. Once that is your conception of politics, the trouble with democracy starts to look like citizens with dysfunctional brains. When our fellow Americans are recast as cognitively broken, it becomes all too easy to believe that it would be best to exclude or diminish the influence of people who believe outrageous things. Increased gatekeeping within the media or by party elites and scientific experts begins to look really attractive. Some, like philosopher Jason Brennan, go even further. His 2016 book, Against Democracy, contends that the ability to rule should be limited to those capable of discerning and “correctly” reasoning about the facts, while largely sidestepping the question of who decides what the right facts are and how to know when we are correctly reasoning about them. But it is misguided to think that making our democracy only more elitist will throttle the wildfire spread of conspiratorial thinking. If anything, doing so will only temporarily contain populist ferment, letting pressure build until it eventually explodes or (if we are lucky) economic growth leads it to fizzle out. Political gatekeeping, by mistaking supposed deficits in truth and rationality for the source of democratic discord, fails to address the underlying cause of our political dysfunction: the lack of trust. Signs of our political system’s declining legitimacy are not difficult to find. A staggering 71 percent of the Americans believe that elected officials don’t care about the average citizen or what they think. Trust in our government has never been lower, with only 17 percent of citizens expressing confidence about Washington most or all the time. By diagnosing rather than understanding, we cannot see that conspiratorial thinking is the symptom rather than the disease. The spread of bizarre theories about COVID-19 being a “planned” epidemic or child-abuse rings is a response to real feelings of helplessness, isolation, and mistrust as numerous natural and manmade disasters unfold before our eyes—epochal crises that governments seem increasingly incapable of getting a handle on. Many of Hofstadter’s listed examples of conspiratorial thought came during similar moments: at the height of the Red Scare and Cold War nuclear brinkmanship, during the 1890s depression, or in the midst of pre-Civil War political fracturing. Conspiracy theories offer a simplified world of bad guys and heroes. A battle between good and evil is a more satisfying answer than the banality of ineffectual government and flawed electoral systems when one is facing wicked problems. Perhaps social media adds fuel to the fire, accelerating the spread of outlandish proposals about what ails the nation. But it does so not because it short-circuits our neural pathways to crash our brains’ rational thinking modules. Conspiracy theories are passed by word of mouth (or Facebook likes) by people we already trust. It is no surprise that they gain traction in a world where satisfying solutions to our chronic, festering crises are hard to find, and where most citizens are neither afforded a legible glimpse into the workings of the vast political machinery that determines much of their lives nor the chance to actually substantially influence it. Will we be able to reverse course before it is too late? If mistrust and unresponsiveness is the cause, the cure should be the effort to reacquaint Americans with the exercise of democracy on a broad-scale. Hofstadter himself noted that, because the political process generally affords more extreme sects little influence, public decisions only seemed to confirm conspiracy theorists’ belief that they are a persecuted minority. The urge to completely exclude “irrational” movements forgets that finding ways to partially accommodate their demands is often the more effective strategy. Allowing for conscientious objections to vaccination effectively ended the anti-vax movement in early 20th century Britain. Just as interpersonal conflicts are more easily resolved by acknowledging and responding to people’s feelings, our seemingly intractable political divides will only become productive by allowing opponents to have some influence on policy. That is not to say that we should give into all their demands. Rather it is only that we need to find small but important ways for them to feel heard and responded to, with policies that do not place unreasonable burdens on the rest of us. While some might pooh-pooh this suggestion, pointing to conspiratorial thinking as evidence of how ill-suited Americans are for any degree of political influence, this gets the relationship backwards. Wisdom isn’t a prerequisite to practicing democracy, but an outcome of it. If our political opponents are to become more reasonable it will only be by being afforded more opportunities to sit down at the table with us to wrestle with just how complex our mutually shared problems are. They aren’t going anywhere, so we might as well learn how to coexist. America’s nuclear energy situation is a microcosm of the nation’s broader political dysfunction. We are at an impasse, and the debate around nuclear energy is highly polarized, even contemptuous. This political deadlock ensures that a widely disliked status quo carries on unabated. Depending on one’s politics, Americans are left either with outdated reactors and an unrealized potential for a high-energy but climate-friendly society, or are stuck taking care of ticking time bombs churning out another two thousand tons of unmanageable radioactive waste every year

Continue reading at The New Atlantis Anyone who knows the history of major disasters like the BP oil spill will have noticed one common feature: overconfidence in the face of the unknown, or what most of us know as foolhardiness. If US colleges are to avoid being mentioned in those kinds of history books, residents, students, and parents need to demand that university presidents reverse course on their campus reopening plans.

Many institutions of higher learning across the nation find themselves in a precarious financial position. They face declining enrollments, oil bust-driven decreases in funding, and the costs of COVID-related protections. Throughout history, organizations in charge of serious hazards have had to grapple with similar economic pressures. And many of them have made unwise decisions as a result. The disaster in Bhopal, India that took the lives of thousands of people was the result of cost cutting measures by Union Carbide, which fundamentally undermined their chemical plants’ safety systems. More recently, Boeing stifled dissent about destabilizing design changes to their 737 MAX jets, because they were preoccupied with not losing market share to Airbus. There is an implicit cost-benefit analysis behind university administrators’ justification for reopening. They have balanced the chance of a handful of students in the ICU—perhaps one or more dead—against ensuring a higher quality “educational experience” and shoring up enrollment numbers as well as room and board revenues. No doubt private companies and regulators do the same thing every day when they decide whether it is worth including additional safety features in cars or if extra road and highway deaths caused by high speed limits are a fair price for giving drivers a quicker commute. But the hazard presented by reopening universities is a different class of risk altogether: Car accidents don’t spread exponentially. We risk repeating the mistaken thinking of Union Carbide or Boeing, courting disaster in the pursuit of more modest gains (or the avoidance of losses). Rather than accept the certain costs of decreased enrollment and of the absence of on-campus students, administrators have bet the farm on in-person and “hybrid” semesters, gambling on unproven strategies meant to keep college students from being socially intimate with each other. If they succeed, the spoils will be modest: Their own institutions won’t lose much ground to peer colleges. If they end up sparking a major outbreak, the damage may prove ruinous to their institution’s reputation and financial solvency, not to mention the harms to nearby residents and local healthcare systems. There are reasons why intelligent people don’t play Russian Roulette. You only get to lose once. We can do far better than gamble with the lives of students, staff, faculty, and community members in order to avoid moderate financial losses. Forward-looking institutions will instead focus on attracting enrollment by drastically improving the quality of online delivery and on redoubling their efforts to attract dollars through research proposals and contract work. There is no guarantee that such efforts would bear fruit, but at least the losses would be known and plausibly manageable. Far too many universities and colleges are committing themselves to the institutional equivalent of Pamplona’s “running of the bulls,” where "winning" only means avoiding mortal injury. There is still time to change course. But will wiser heads prevail? |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed