|

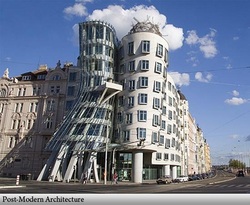

A recent interview in The Atlantic with a man who believes himself to be in a relationship with two “Real Dolls” illustrates what I think is one of the most significant challenges raised by certain technological innovations as well as the importance of holding on to the idea of authenticity in the face of post-modern skepticism. Much like Evan Selinger’s prescient warnings about the cult of efficiency and the tendency for people to recast traditional forms of civility as onerous inconveniences in response to affordances of new communication technologies, I want to argue that the burdens of human relationships, of which “virtual other” technologies promise to free their users, are actually what makes them valuable and authentic.[1] The Atlantic article consists of an interview with “Davecat,” a man who owns and has “sex” with two Real Dolls – highly realistic-looking but inanimate silicone mannequins. Davecat argues that his choice to pursue relationships with “synthetic humans” is a legitimate one. He justifies his lifestyle preferences by contending that “a synthetic will never lie to you, cheat on you, criticize you, or be otherwise disagreeable.” The two objects of his affection are not mere inanimate objects to Davecat but people with backstories, albeit ones of his own invention. Davecat presents himself as someone fully content with his life: “At this stage in the game, I'd have to say that I'm about 99 percent fulfilled. Every time I return home, there are two gorgeous synthetic women waiting for me, who both act as creative muses, photo models, and romantic partners. They make my flat less empty, and I never have to worry about them becoming disagreeable.” In some ways, Davecat’s relationships with his dolls are incontrovertibly real. His emotions strike him as real, and he acts as if his partners were organic humans. Yet, in other ways, they are inauthentic simulations. His partners have no subjectivities of their own, only what springs from Davecat’s own imagination. They “do” only what he commands them to do. They are “real” people only insofar as they are real to Davecat’s mind and his alone. In other words, Davecat’s romantic life amounts to a technologically afforded form of solipsism. Many fans of post-modernist theory would likely scoff at the mere word, authenticity being as detestable as the word “natural” as well as part and parcel of philosophically and politically suspect dualisms. Indeed, authenticity is not something wholly found out in the world but a category developed by people. Yet, in the end, the result of post-modern deconstruction is not to get to truth but to support an alternative social construction, one ostensibly more desirable to the person doing the deconstructing.  As the philosopher Charles Taylor[2] has outlined, much of contemporary culture and post-modernist thought itself is dominated by an ideal of authenticity no less problematic. That ethic involves the moral imperative to “be true to oneself” and that self-realization and identity are both inwardly developed. Deviant and narcissistic forms of this ethic emerge when the dialogical character of human being is forgotten. It is presumed that the self can somehow be developed independently of others, as if humans were not socially shaped beings but wholly independent, self-authoring minds. Post-modernist thinkers slide toward this deviant ideal of authenticity, according to Taylor, in their heroization of the solitary artist and their tendency to equate being with the aesthetic. One need only look to post-modernist architecture to see the practical conclusions of such an ideal: buildings constructed without concern for the significance of the surrounding neighborhood into which it will be placed or as part of continuing dialogue about architectural significance. The architect seeks only full license to erect a monument to their own ego. Non-narcissistic authenticity, as Taylor seems to suggest, is realizable only in self-realization vis-à-vis the intersubjective engagement with others. As such, Davecat’s sexual preferences for “synthetic humans” do not amount to a sexual orientation as legitimate as those of homosexuals or other queer peoples who have strived for recognition in recent decades. To equate the two is to do the latter a disservice. Both may face forms of social ridicule for their practices but that is where the similarities end. Members of homosexual relationships have their own subjectivities, which each must negotiate and respect to some extent if the relationship itself is to flourish. All just and loving relationships involve give-and-take, compromise and understanding and sometimes, hardship and disappointment. Davecat’s relationship with his dolls is narcissistic because there is no possibility for such a dialogue and the coming to terms with his partners’ subjectivities. In the end, only his own self-referential preferences matter. Relationships with real dolls are better thought of as morally commodified versions of authentic relationships. Borgmann[3] defines a practice as morally commodified “when it is detached from its context of engagement with a time, a place, and a community” (p. 152). Although Davecat engages in a community of “iDollators,” his interactions with his dolls has is detached from the context of engagement typical for human relationships. Much like how mealtimes are morally commodified when replaced by an individualize “refueling” at a fast-food joint or with a microwave dinner, Davecat’s dolls serve only to “refuel” his own psychic and sexual needs at the time, place and manner of his choosing. He does not engage with his dolls but consumes them. At the same time, “virtual other” technologies are highly alluring. They can serve as “techno-fixes” to those lacking the skills or dispositions needed for stable relationships or those without supportive social networks (e.g., the elderly). Would not labeling them as inauthentic demean the experiences of those who need them? Yet, as currently envisioned, Real Dolls and non-sexually-oriented virtual other technologies do not aim to render their users more capable of human relationships or help them become re-established in a community of others but provide an anodyne for their loneliness, an escape from or surrogate for the human social community of which they find themselves on the outside. Without a feasible pathway toward non-solipsistic relationships, the embrace of virtual other technologies for the lonely and relationally inept amounts to giving up on them, which suggests that it is better for them to remain in a state of arrested development. Another danger is well articulated by the psychologist Sherry Turkle.[4] Far from being mere therapeutic aids, such devices are used to hide from the risks of social intimacy and risk altering collective expectations for human relationships. That is, she worries that the standards of efficiency and egoistic control afforded by robots comes to be the standard by which all relationships come to be judged. Indeed, her detailed clinical and observational data belies just such a claim. Rather than being able to simply wave off the normalizing and advancement of Real Dolls and similar technologies as a “personal choice,” Turkle’s work forces one to recognize that cascading cultural consequences result from the technologies that societies permit to flourish. The amount of dollars spent on technological surrogates for social relationships is staggering. The various sex dolls on the market and the robots being bought for nursing homes cost several thousand dollars apiece. If that money could be incrementally redirected, through tax and subsidy, toward building the kinds of material, economic and political infrastructures that have supported community at other places and times, there would be much less need for such techno-fixes. Much like what Michele Willson[5] argues about digital technologies in general, they are technologies “sought to solve the problem of compartmentalization and disconnection that is partly a consequence of extended and abstracted relations brought about by the use of technology” (p. 80). The market for Real Dolls, therapy robots for the elderly and other forms of allaying loneliness (e.g., television) is so strong because alternatives have been undermined and dismantled. The demise of rich opportunities for public associational life and community-centering cafes and pubs has been well documented, hollowed out in part by suburban living and the rise of television. [6] The most important response to Real Dolls and other virtual other technologies is to actually pursue a public debate about what citizens’ would like their communities to look like, how they should function and which technologies are supportive of those ends. It would be the height of naiveté to presume the market or some invisible hand of technological innovation simply provides what people want. As research in Science and Technology Studies make clear, technological innovation is not autonomous, but neither has it been intelligently steered. The pursuit of mostly fictitious and narcissistic relationships with dolls is of questionable desirability, individually and collectively; a civilization that deserves the label of civilized would not sit idly by as such technologies and its champions alter the cultural landscape by which it understands human relationships. ____________________________________ [1] I made many of these same points in an article I published last year in AI & Society, which will hopefully exit “OnlineFirst” limbo and appear in an issue at some point. [2] Taylor, Charles. (1991). The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [3] Borgmann, Albert. (2006). Real American Ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [4] Turkle, Sherry. (2012). Alone Together. New York: Basic Books. [5] Willson, Michele. (2006). Technically Together. New York: Peter Lang. [6] See: Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone. New York: Simon & Schuster and Oldenburg, Ray. (1999). The Great Good Place. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. Comments are closed.

|

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed