|

5/15/2014 What Was Step Two Again? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress.Read Now Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Far too rarely do most people reflect critically on the relationship between advancing technoscience and progress. The connection seems obvious, if not “natural.” How else would progress occur except by “moving forward” with continuous innovation? Many, if not most, members of contemporary technological civilization seem to possess an almost unshakable faith in the power of innovation to produce an unequivocally better world. Part of the purpose of Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholarship is to precisely examine if, when, how and for whom improved science and technology means progress. Failing to ask these questions, one risks thinking about technoscience like how underpants gnomes think about underwear. Wait. Underpants gnomes? Let me back up for second. The underpants gnomes are characters from the second season of the television show South Park. They sneak into people’s bedrooms at night to steal underpants, even the ones that their unsuspecting victims are wearing. When asked why they collect underwear, the gnomes explain their “business plan” as follows: Step 1) Collect underpants, Step 2) “?”, Step 3) Profit! The joke hinges on the sheer absurdity of the gnomes’ single-minded pursuit of underpants in the face of their apparent lack of a clear idea of what profit means and how underpants will help them achieve it. Although this reference is by now a bit dated, these little hoarders of other people’s undergarments are actually one of the best pop-culture illustrations of the technocratic theory of progress that often undergirds people’s thinking about innovation. The historian of technology Leo Marx described the technocratic idea of progress as: "A belief in the sufficiency of scientific and technological innovation as the basis for general progress. It says that if we can ensure the advance of science-based technologies, the rest will take care of itself. (The “rest” refers to nothing less than a corresponding degree of improvement in the social, political, and cultural conditions of life.)" The technocratic understanding of progress amounts to the application of underpants gnome logic to technoscience: Step 1) Produce innovations, Step 2) “?”, Step 3) Progress! This conception of progress is characterized by a lack of a clear idea of not only what progress means but also how amassing new innovations will bring it about.

The point of undermining this notion of progress is not to say that improved technoscience does not or could not play an important role in bringing about progress but to recognize that there is generally no logical reason for believing it will automatically and autonomously do so. That is, “Step 2” matters a great deal. For instance, consider the 19th century belief that electrification would bring about a radical democratization of America through the emancipation of craftsmen, a claim that most people today will recognize as patently absurd. Given the growing evidence that American politics functions more like an oligarchy than a democracy, it would seem that wave after wave of supposedly “democratizing” technologies – from television to the Internet – have not been all that effective in fomenting that kind of progress. Moreover, while it is of course true that innovations like the polio vaccine, for example, certainly have meant social progress in the form of fewer people suffering from debilitating illnesses, one should not forget that such progress has been achievable only with the right political structures and decisions. The inventor of the vaccine, Jonas Salk, notably did not attempt to patent it, and the ongoing effort to eradicate polio has entailed dedicated global-level organization, collaboration and financial support. Hence, a non-technocratic civilization would not simply strive to multiply innovations under the belief that some vague good may eventually come out of it. Rather, its members would be concerned with whether or not specific forms of social, cultural or political progress will in fact result from any particular innovation. Ensuring that innovations lead to progress requires participants to think politically and social scientifically, not just technically. More importantly, it would demand that citizens consider placing limits on the production of technoscience that amounts to what Thoreau derided as “improved means to unimproved ends.” Proceeding more critically and less like the underpants gnomes means asking difficult and disquieting questions of technoscience. For example, pursuing driverless cars may lead to incremental gains in safety and potentially free people from the drudgery of driving, but what about the people automated out of a job? Does a driverless car mean progress to them? Furthermore, how sure should one be of the presumption that driverless cars (as opposed to less automobility in general) will bring about a more desirable world? Similarly, how should one balance the purported gains in yield promised by advocates of contemporary GMO crops against the prospects for a greater centralization of power within agriculture? How much does corn production need to increase to be worth the greater inequalities, much less the environmental risks? Moreover, does a new version of the iPhone every six months mean progress to anyone other than Apple’s shareholders and elite consumers? It is fine, of course, to be excited about new discoveries and inventions that overcome previously tenacious technical problems. However, it is necessary to take stock of where such innovations seem to lead. Do they really mean progress? More importantly, whose interests do they progress and how? Given the collective failure to demand answers to these sorts of questions, one has good reason to wonder whether technological civilization really is making progress. Contrary to the vision of humanity being carried up to the heavens of progress upon the growing peaks of Mt. Innovation, it might be that many of us are more like underpants gnomes dreaming of untold and enigmatic profits amongst piles of what are little better than used undergarments. One never knows unless one stops collecting long enough to ask, “What was step two again?” Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered

Despite all the potential risks of driverless cars and the uncertainty of actually realizing their benefits, totally absent from most discussions of this technology is the possibility of rejecting it. On the Atlantic Cities blog, for instance, Robin Chase recently wondered aloud whether a future with self-driving cars will be either heaven or hell. Although it is certainly refreshing that she eschews the techno-idealism and hype that too often pervades writing about technology, she nonetheless never pauses to consider if they really must be “the future.” Other writing on the subject is much less nuanced than even what Chase offers. A writer on the Freakanomics blog breathlessly describes driverless technology as a “miracle innovation” and a “pending revolution.” The implication is clear: Driverless cars are destined to arrive at your doorstep. Why is it that otherwise intelligent people seem to act as if autopiloted automobiles were themselves in the driver’s seat, doing much of the steering of technological development for humanity? The tendency to approach the development of driverless cars fatalistically reflects the mistaken belief that technology mostly evolves according to its own internal logic: i.e., that technology writ large progresses autonomously. With this understanding of technology, humanity’s role, at best, is simply to adapt as best they can and address the unanticipated consequences but not attempt to consciously steer or limit technological innovation. The premise of autonomous technology, however, is undermined by the simple social scientific observation of how technologies actually get made. Which technologies become widespread is as much sociopolitical as technical. The dominance of driving in the United States, for instance, has more to do with the stifling municipal regulation on and crushing debts held by early 20th century transit companies, the Great Depression, the National Highway Act and the schemes of large corporations like GM and Standard Oil to eliminate streetcars than the purported technical desirability of the automobile. Indeed, driverless cars can only become “the future” if regulations allow them on city streets and state highways. Citizens could collectively choose to forgo them. The cars themselves will not lobby legislatures to allow them on the road; only the companies standing to profit from them will. How such simple observations are missed by most people is a reflection of the entrenchment of the idea of autonomous technology in their thinking. Certain technologies only seem fated to dominate technological civilization because most people are relegated to the back seat on the road to “progress,” rarely being allowed to have much say concerning where they are going and how to get there. Whether or not citizens’ lives are upended or otherwise negatively affected by any technological innovation is treated as mainly a matter for engineers, businesses and bureaucrats to decide. The rest of us are just along for the ride. A people-driven, rather than technology or elite-driven, approach to the driverless cars would entail implementing something like what Edward Woodhouse has called the “Intelligent Trial and Error” steering of technology. An intelligent trial and error approach recognizes that, given the complexity and uncertainty surrounding any innovation, promises are often overstated and significant harms overlooked. No one really knows for sure what the future holds. For instance, automating driving might fail to deliver on promised decreases in vehicles on the road and miles driven if it contributes to accelerating sprawl and its lower costs leads to more frequent and frivolous trips and deliveries. The first step to the intelligent steering of driverless car technology would be to involve those who might be negatively affected. Thus far, most of the decision making power lies with less-than-representative political elites and large tech firms, the latter obviously standing to benefit a great deal if and when they get the go ahead. There are several segments of the population likely to be left in the ditch in the process of delivering others to "the future." Drastically lowering the price of automobile travel will undermine the efforts of those who desire to live in more walkable and dense neighborhoods. Automating driving will likely cause the massive unemployment of truck and cab drivers. Current approaches to (poorly) governing technological development are poised to render these groups victims of “progress” rather than participants in it. Including them could open up previously unimagined possibilities, like moving forward with driverless cars only if financial and regulatory support could be suitably guaranteed for redensifying urban areas and the retraining, social welfare and eventual placement in livable wage jobs for the workers made obsolete. Taking the sensible initial precaution of gradually scaling-up developments is another component of intelligent trial and error. For self-driving cars, this would mostly entail more extensive testing than is currently being pursued. The experiences of a few dozen test vehicles in Nevada or California hardly provide any inkling of the potential long-term consequences. Actually having adequate knowledge before proceeding with autonomous automobiles would likely require a larger-scale implementation of them within a limited region for a period of five years if not more than a decade. During this period, this area would need to be monitored by a wide range of appropriate experts, not just tech firms with obvious conflicts of interest. Do these cars promote hypersuburbanization? Are they actually safer, or do aggregations of thousands of programmed cars produce emergent crashes similar to those created by high-frequency trading algorithms? Are vehicle miles really substantially affected? Are citizens any happier or noticeably better off, or do driverless commutes just amount to more unpaid telework hours and more time spent improving one’s Candy Crush score? Doing this kind of testing for autopiloted automobiles would be simply extending the model of the FDA, which Americans already trust to ensure that their drugs cure rather than kill them, to technologies with the potential for equally tragic consequences. If and only if driverless cars were to pass these initial hurdles, a sane technological civilization would then implement them in ways that were flexible and fairly easy to reverse. Mainly this would entail not repeating the early 20th century American mistake of dismantling mass transit alternatives or prohibiting walking and biking through autocentric design. The recent spikes in unconventional fossil fuel production aside, resource depletion and climate change are likely to eventually render autopiloted automobiles an irrational mode of transportation. They depend on the ability to shoot expensive communication satellites into space and maintain a stable electrical grid, both things that growing energy scarcity would make more difficult. If such a future came to pass self-driving cars would end up being the 21st century equivalent of the abandoned roadside statues of Easter Island: A testament to the follies of unsustainable notions of progress. Any intelligent implementation of driverless cars would not leave future citizens with the task of having to wholly dismantle or desert cities built around the assumption of forever having automobiles, much less self-driving ones. There, of course, are many more details to work out. Regardless, despite any inconveniences that an intelligent trial and error process would entail, it would beat what currently passes for technology assessment: Talking heads attempting to predict all the possible promises and perils of a technology while it is increasingly developed and deployed with only the most minimal of critical oversight. There is no reason to believe that the future of technological civilization was irrevocably determined once Google engineers started placing self-driving automobiles on Nevada roads. Doing otherwise would merely require putting the broader public back into the driver’s seat in steering technological development. Peddling educational media and games is a lot like selling drugs to the parents of sick children: In both cases, the buyers are desperate. Those buying educational products often do so out of concern (or perhaps fear) for their child’s cognitive “health” and, thereby, their future as employable and successful adults. The hope is that some cognitive “treatment,” like a set of Baby Einstein DVDs or an iPad app, will ensure the “normal” mental development of their child, or perhaps provide them an advantage over other children. These practices are in some ways no different than anxiously shuttling infants and toddlers to pediatricians to see if they “are where they should be” or fretting over proper nutrition. However, the desperation and anxiety of parents serves as an incentive for those who develop and sell treatment options to overstate their benefits, if not outright deceive. Although regulations and institutions (i.e., the FDA) exist to help that ensure parents concerned about their son or daughter’s physiological development are not being swindled, those seeking to improve or ensure proper growth of their child’s cognitive abilities are on their own, and the market is replete with the educational equivalent of snake oil and laudanum.

Take the example of Baby Einstein. The developers of this DVD series promise that they are designed to “enrich your baby’s happiness” and “encourage [their] discovery of the world.” The implicit reference to Albert Einstein is meant to persuade parents that these DVDs provide a substantial educational benefit. Yet, there is good reason to be skeptical of Baby Einstein. The American Academy of Pediatrics, for instance, recommends against exposing children under two to television and movies to children as a precaution against the potential development harms. A 2007 study broke headlines when researchers found evidence that the daily watching of educational DVDs like Baby Einstein may slow communicative development in infants but had no significant effects on toddlers[1]. At the time, parents were already shelling out $200 million a year to Baby Einstein with the hope of stimulating their child’s brain. What they received, however, was likely no more than an overhyped electronic babysitter. Today, the new hot market for education technology is not DVDs but iPad and smartphone apps. Unsurprisingly, the cognitive benefits provided by them are just as uncertain. As Celilia Kang notes, “despite advertising claims, there are no major studies that show whether the technology is helpful or harmful.” Given this state of uncertainty, firms can overstate the benefits provided by their products and consumers have little to guide them in navigating the market. Parents are particularly easy marks. Much like how an individual receiving a drug or some other form of medical treatment is often in a poor epistemological position to evaluate its efficacy (they have little way of knowing how they would have turned out without treatment or with an alternative), parents generally cannot effectively appraise the cognitive boost given to their child by letting them watch a Baby Einstein DVD or play an ostensibly literacy-enhancing game on their iPad. They have no way of knowing if little Suzy would have learned her letters faster or slower with or without the educational technology, or if it were substituted with more time for play or being read to. They simply have no point of comparison. Lacking a time machine, they cannot repeat the experiment. Move over, some parents might be motivated to look for reasons to justify their spending on educational technologies or simply want to feel that they have agency in improving their child’s capacities. Therefore, they are likely to suffer from a confirmation bias. It is far too easy for parents to convince themselves that little David counted to ten because of their wise decision to purchase an app that bleats the numbers out of the tablet’s speakers when they jab their finger toward the correct box. Educational technologies have their own placebo effect. It just so happens to affect the minds of parents, not the child using the technology. Moreover, determining whether or not one’s child has been harmed is no easy matter. Changes in behavior could be either over or under estimated depending on to what extent parents suffers from an overly nostalgic memory of their own childhood or generational amnesia concerning real significant differences. Yet, it is not only parents and their children who may be harmed by wasting time and money on learning technologies that are either not substantively more effective or even cognitively damaging. School districts spend billions of taxpayer money on new digital curricula and tools with unproven efficacy. There are numerous products, from Carengie’s “Cognitive Tutor” to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s “Destination Reading,” that make extravagant claims about their efficacy but have been found not to significantly improve learning outcomes over traditional textbooks when reviewed by the Department of Education. Nevertheless, both are still for sale. Websites for these software packages claim that they are “based on over 20 years of research into how students think and learn” and “empirical research and practice that helps identify, prevent, and remediate reading difficulties.” Nowhere is it stated on the companies’ websites that third party research suggests that these expensive pieces of software may not actually improve outcomes. Even if some educational technologies prove to be somewhat more effective than a book or numbered blocks, they may still be undesirable for other reasons. Does an app cut into time that might otherwise be spent playing with parents or siblings? Children, on average, already spend seven hours each day in front of screens, which automatically translates into less time spent outdoors on non-electronic hobbies and interactions. The cultural presumption that improved educational outcomes always lie with the “latest and greatest” only exacerbates this situation. Do educational technologies in school districts come at the costs of jobs for teachers or cut into budgets for music and arts programs? The Los Angeles school district has cut thousands of teachers from their payroll in recent years but, as Carlo Rotella notes, is spending $500 million in bond money to purchase iPads. All the above concerns do not even broach the subject of how people raised on tablets might be changed in undesirable ways as a result. What sorts of expectations, beliefs and dispositions might their usage be more compatible? Given concerns about how technologies like the Internet influence how people think in general, concerned citizens should not let childhood be dominated by them without adequate debate and testing. Because of the potential for harm, uncertainty of benefit and the difficulty for consumers to be adequately informed concerning either, the US should develop an equivalent to the FDA for educational technologies. Many Americans trust the FDA to prevent recurrences of pharmaceutical mistakes like thalidomide, the morning sickness drug that led to dead and deformed babies. Why not entrust a similar institution to help ensure that future children are not cognitively stunted, as may have happened with Baby Einstein DVDs, or simply that parents and school districts do not waste money on the educational equivalent of 19th century hair tonics and “water cures?” The FDA, of course, is not perfect. Some aspects of human health are too complex to be parsed out through the kinds of experimental studies the FDA requires. Just think of the perpetual controversy over what percentage of people’s diet should come from fats, proteins and starches. Likewise, some promising treatments may never get pursued because the return on investment may not match the expenses incurred in getting FDA approval. The medicinal properties of some naturally occurring substances, for instance, have often not been substantively tested because, in that state, they cannot be patented. Finally, how to intervene in the development of children is ultimately a matter of values. Even pediatric science has been shaped by cultural assumptions about what an ideal adult looks like. For instance, mid-twentieth century pediatricians insisted, in contrast to thousands of years of human history, that sleeping alone promoted the healthiest outcomes for children. Today, it is easy to recognize that such science was shaped by Western myths of the self-reliant or rugged individual. The above problems would likely also affect any proposed agency for assessing educational technologies. What makes for “good” education depends on one's opinion concerning what kind of person education ought to produce. Is it more important that children can repeat the alphabet or count to ten at earlier and earlier ages or that they can approach the world with not only curiosity and wonder but also as a critical inquirer? Is the extension of the logic and aims of the formal education system to earlier and earlier ages via apps and other digital devices even desirable? Why not redirect some of the money going to proliferating iPad apps and robotic learning systems to ensuring all children have the option to attend something more like the "forest kindergartens" that have existed in Germany for decades? No scientific study that can answer such questions. Nevertheless, something like an Educational Technology Association would, in any case, represent one step toward a more ethically responsible and accountable educational technology industry. _______________________________________ [1] Like any controversial study, its findings are a topic of contention. Other scholars have suggested that the data could be made to show a positive, negative or neutral result, depending on statistical treatment. The authors of the original study have countered, arguing that the critics have not undermined the original conclusion that the educational benefits of these DVDs are dubious at best and may crowd-out more effective practices like parents reading to their children. On my last day in San Diego, I saw a young woman get hit by the trolley. The gasps of other people waiting on the platform prompted me to look up just as she was struck and then dragged for several feet. Did the driver come in too fast? Did he not use his horn? Had she been distracted by her phone? I do not know for certain, though her cracked smartphone was lying next to her motionless body. Good Samaritans, more courageous and likely more competent in first aid than myself, rushed to help her before I got over my shock and dropped my luggage. For weeks afterwards, I kept checking news outlets only to find nothing. Did she live? I still do not know. What I did discover is that people are struck by the trolley fairly frequently, possibly more often than one might expect. Many, like the incident I witnessed, go unreported in the media. Why would an ostensibly sane technological civilization tolerate such a slowly unfolding and piecemeal disaster? What could be done about it?

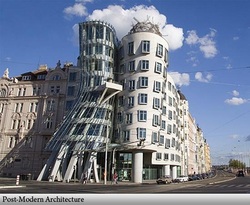

I do not know of any area of science and technology studies that focuses on the kinds of everyday accidents killing or maiming tens or hundreds of thousands of people every year, even though examples are easy to think of: everything from highway fatalities to firearm accidents. The disasters typically focused on are spectacular events, such as Three Mile Island, Bhopal or the Challenger explosion, where many people die and/or millions bear witness. Charles Perrow, for instance, refers to the nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island as a “normal accident:” an unpredictable but unavoidable consequence of highly complex and tightly coupled technological systems. Though seemingly unrelated, the tragedy I witnessed was perhaps not so different from a Three Mile Island or a Challenger explosion. The light rail trolley in San Diego is clearly a very complex sociotechnical system relying on electrical grids, signaling systems at grade crossing as well as the social conditioning of behaviors meant to keep riders out of danger. Each passenger as well as could be viewed as component of a large sociotechnical network of which their life is but one component. The young woman I saw, if distracted by her phone, may have been a casualty of a global telecommunications network, dominated by companies interested in keeping customers engrossed in their gadgets, colliding with that of the trolley car. Any particular accident causing the injury or death of a pedestrian might be unpredictable but the design of these systems, now coupled and working at cross purposes, would seem to render accidents in general increasingly inevitable. A common tendency when confronted with an accident, however, is for people to place all the blame on individuals and not on systems. Indeed, after the event I witnessed, many observers made their theories clear. Some blamed the driver for coming too fast. Others claimed the injured young woman was looking at her phone and not her surroundings. A man on the next train I boarded even muttered, “She probably jumped” under his breath. I doubt this line of reasoning is helpful for improving contemporary life, as useful as it might be for witnesses to quickly make sense of tragedy or those most culpable to assuage their guilt. At the end of the day, a young woman either is no longer living or must face a very different life than she envisioned for herself; friends, family and maybe a partner must endure personal heartbreak; and a trolley driver will struggle to live the memory of the incident. Victim blaming likely exacerbates the degree to which the status quo and potentially helpful sociotechnical changes are left unexamined. Indeed, Ford actively used the strategy of blaming individual drivers to distract attention away from the fact that the design of the gas tank in the Pinto was inept and dangerous. The platform where the accident occurred had no advance warning system for arriving trains. It was an elevated platform, which eliminated the need for grade crossings but also had the unintended consequence of depriving riders of the benefit of their flashing red lights and bells. Unlike metros, the trolley trains operate near the grade level of the platform. Riders are often forced to cross the tracks to either exit the platform or switch lines. The trolleys are powered by electricity and are eerily silent, except for a weak horn or bell that is easy to miss if one is not listening for it (and it may often come too late anyway). At the same time, riders are increasingly likely to have headphones on or have highly alluring and distracting devices in their hands or pants pockets. Technologically encouraged “inattention blindness” has been receiving quite a lot of attention as increasingly functional mobile devices flood the market. Apart from concerns about texting while driving and other newly emerging habits, there are worries that such devices have driven the rise in pedestrian and child accidents. British children on average receive their first cell phone at eleven years old, paralleling a three-fold increase in their likelihood of dying or being severely injured on the way to school. Although declining for much of a decade, childhood accident rates have risen in the US over the last few years. Some suggest that smartphones have fueled an increase in accidents stemming from “distracted parenting.” Of course, inattention blindness is not solely a creation of the digital age, one thinks of stories told about Pierre Curie dying after inattentively crossing the street and getting run over by a horse-drawn carriage. Yet, it would definitely be act of intentional ignorance to not note the particular allures of digital gadgetry. What if designers of trolley stations were to presume that riders would likely be distracted, with music blaring in their ears, engrossed in a digital device or simply day dreaming? It seems like a sensible and simple precaution to include lights and audio warnings. The Edmonton LRT, for instance, alerts riders of incoming trains. Physically altering the platform architecture, however, seems prohibitively expensive in the short term. A pedestrian bridge installed in Britain after a teenage girl was struck cost about two million pounds. A more radical intervention might be altering cell phone systems or Wi-Fi networks so that devices are frozen with a warning message when a train is arriving or departing, allowing, of course, for unimpeded phone calls to 911. Yet, the feasibility or existence of potentially helpful technological fixes does not mean they will be implemented. Trolley systems and municipalities may need to be induced or incentived to include them. Given the relative frequency of incidents in San Diego, for instance, it seems that the mere existence of a handful or more injuries or deaths per year is insufficient by itself. I would not want to presume that the San Diego Metropolitan Transit Service is acting like Ford in the Pinto case: intentionally not fixing a dangerous technology because remedying the problem is more expensive than paying settlements with victims. Perhaps it is simply a case of “normalized deviance,” in which an otherwise unusual event is eventually accepted as a natural or normal component of reality. Nevertheless, continuous non-decision has the same consequences as intentional neglect. It is not hard to envision policy changes might lessen the likelihood of similar events in the future. Audible warning devices could be mandated. Federal regulations are too vague on this matter, leaving too much to the discretion of the operator and transit authority. Light rail systems could be evaluated at a regional or national according to their safety and then face fines or subsidy cuts if accident-frequency remains above a certain level. Technologies that could enhance safety could be subsidized to a level that makes implementation a no-brainer for municipalities. Enabling the broadcast to or freezing of certain digital devices on train platforms would clearly require technological changes in addition to political ones. Currently Wi-Fi and cell signals are not treated as public to the same degree as broadcast TV and radio. Broadcasts on the latter two are frequently interrupted in the case of emergencies, but the former are not. Given the declining share of the average Americans media diet that television and radio compose, it seems reasonable to seek to extend the reach and logic of the Emergency Alert System to other media technologies and for other public purposes. Much like the unthinking acceptance of the tens of thousands of lives lost each year on American roads and highways, it would too easy to view accidents like the one I saw as simply a statistical certainty or, even worse, the “price of modernity.” Every accident is a tragedy, a mini-disaster in the life of a person and those connected with them. It is easy to imagine simple design changes and technological interventions that could have reduced the likelihood of such events. They are neither expensive nor require significant advances in technoscientific know-how. A sane technological civilization would not neglect such simple ways of lessening needless human suffering. A recent interview in The Atlantic with a man who believes himself to be in a relationship with two “Real Dolls” illustrates what I think is one of the most significant challenges raised by certain technological innovations as well as the importance of holding on to the idea of authenticity in the face of post-modern skepticism. Much like Evan Selinger’s prescient warnings about the cult of efficiency and the tendency for people to recast traditional forms of civility as onerous inconveniences in response to affordances of new communication technologies, I want to argue that the burdens of human relationships, of which “virtual other” technologies promise to free their users, are actually what makes them valuable and authentic.[1] The Atlantic article consists of an interview with “Davecat,” a man who owns and has “sex” with two Real Dolls – highly realistic-looking but inanimate silicone mannequins. Davecat argues that his choice to pursue relationships with “synthetic humans” is a legitimate one. He justifies his lifestyle preferences by contending that “a synthetic will never lie to you, cheat on you, criticize you, or be otherwise disagreeable.” The two objects of his affection are not mere inanimate objects to Davecat but people with backstories, albeit ones of his own invention. Davecat presents himself as someone fully content with his life: “At this stage in the game, I'd have to say that I'm about 99 percent fulfilled. Every time I return home, there are two gorgeous synthetic women waiting for me, who both act as creative muses, photo models, and romantic partners. They make my flat less empty, and I never have to worry about them becoming disagreeable.” In some ways, Davecat’s relationships with his dolls are incontrovertibly real. His emotions strike him as real, and he acts as if his partners were organic humans. Yet, in other ways, they are inauthentic simulations. His partners have no subjectivities of their own, only what springs from Davecat’s own imagination. They “do” only what he commands them to do. They are “real” people only insofar as they are real to Davecat’s mind and his alone. In other words, Davecat’s romantic life amounts to a technologically afforded form of solipsism. Many fans of post-modernist theory would likely scoff at the mere word, authenticity being as detestable as the word “natural” as well as part and parcel of philosophically and politically suspect dualisms. Indeed, authenticity is not something wholly found out in the world but a category developed by people. Yet, in the end, the result of post-modern deconstruction is not to get to truth but to support an alternative social construction, one ostensibly more desirable to the person doing the deconstructing.  As the philosopher Charles Taylor[2] has outlined, much of contemporary culture and post-modernist thought itself is dominated by an ideal of authenticity no less problematic. That ethic involves the moral imperative to “be true to oneself” and that self-realization and identity are both inwardly developed. Deviant and narcissistic forms of this ethic emerge when the dialogical character of human being is forgotten. It is presumed that the self can somehow be developed independently of others, as if humans were not socially shaped beings but wholly independent, self-authoring minds. Post-modernist thinkers slide toward this deviant ideal of authenticity, according to Taylor, in their heroization of the solitary artist and their tendency to equate being with the aesthetic. One need only look to post-modernist architecture to see the practical conclusions of such an ideal: buildings constructed without concern for the significance of the surrounding neighborhood into which it will be placed or as part of continuing dialogue about architectural significance. The architect seeks only full license to erect a monument to their own ego. Non-narcissistic authenticity, as Taylor seems to suggest, is realizable only in self-realization vis-à-vis the intersubjective engagement with others. As such, Davecat’s sexual preferences for “synthetic humans” do not amount to a sexual orientation as legitimate as those of homosexuals or other queer peoples who have strived for recognition in recent decades. To equate the two is to do the latter a disservice. Both may face forms of social ridicule for their practices but that is where the similarities end. Members of homosexual relationships have their own subjectivities, which each must negotiate and respect to some extent if the relationship itself is to flourish. All just and loving relationships involve give-and-take, compromise and understanding and sometimes, hardship and disappointment. Davecat’s relationship with his dolls is narcissistic because there is no possibility for such a dialogue and the coming to terms with his partners’ subjectivities. In the end, only his own self-referential preferences matter. Relationships with real dolls are better thought of as morally commodified versions of authentic relationships. Borgmann[3] defines a practice as morally commodified “when it is detached from its context of engagement with a time, a place, and a community” (p. 152). Although Davecat engages in a community of “iDollators,” his interactions with his dolls has is detached from the context of engagement typical for human relationships. Much like how mealtimes are morally commodified when replaced by an individualize “refueling” at a fast-food joint or with a microwave dinner, Davecat’s dolls serve only to “refuel” his own psychic and sexual needs at the time, place and manner of his choosing. He does not engage with his dolls but consumes them. At the same time, “virtual other” technologies are highly alluring. They can serve as “techno-fixes” to those lacking the skills or dispositions needed for stable relationships or those without supportive social networks (e.g., the elderly). Would not labeling them as inauthentic demean the experiences of those who need them? Yet, as currently envisioned, Real Dolls and non-sexually-oriented virtual other technologies do not aim to render their users more capable of human relationships or help them become re-established in a community of others but provide an anodyne for their loneliness, an escape from or surrogate for the human social community of which they find themselves on the outside. Without a feasible pathway toward non-solipsistic relationships, the embrace of virtual other technologies for the lonely and relationally inept amounts to giving up on them, which suggests that it is better for them to remain in a state of arrested development. Another danger is well articulated by the psychologist Sherry Turkle.[4] Far from being mere therapeutic aids, such devices are used to hide from the risks of social intimacy and risk altering collective expectations for human relationships. That is, she worries that the standards of efficiency and egoistic control afforded by robots comes to be the standard by which all relationships come to be judged. Indeed, her detailed clinical and observational data belies just such a claim. Rather than being able to simply wave off the normalizing and advancement of Real Dolls and similar technologies as a “personal choice,” Turkle’s work forces one to recognize that cascading cultural consequences result from the technologies that societies permit to flourish. The amount of dollars spent on technological surrogates for social relationships is staggering. The various sex dolls on the market and the robots being bought for nursing homes cost several thousand dollars apiece. If that money could be incrementally redirected, through tax and subsidy, toward building the kinds of material, economic and political infrastructures that have supported community at other places and times, there would be much less need for such techno-fixes. Much like what Michele Willson[5] argues about digital technologies in general, they are technologies “sought to solve the problem of compartmentalization and disconnection that is partly a consequence of extended and abstracted relations brought about by the use of technology” (p. 80). The market for Real Dolls, therapy robots for the elderly and other forms of allaying loneliness (e.g., television) is so strong because alternatives have been undermined and dismantled. The demise of rich opportunities for public associational life and community-centering cafes and pubs has been well documented, hollowed out in part by suburban living and the rise of television. [6] The most important response to Real Dolls and other virtual other technologies is to actually pursue a public debate about what citizens’ would like their communities to look like, how they should function and which technologies are supportive of those ends. It would be the height of naiveté to presume the market or some invisible hand of technological innovation simply provides what people want. As research in Science and Technology Studies make clear, technological innovation is not autonomous, but neither has it been intelligently steered. The pursuit of mostly fictitious and narcissistic relationships with dolls is of questionable desirability, individually and collectively; a civilization that deserves the label of civilized would not sit idly by as such technologies and its champions alter the cultural landscape by which it understands human relationships. ____________________________________ [1] I made many of these same points in an article I published last year in AI & Society, which will hopefully exit “OnlineFirst” limbo and appear in an issue at some point. [2] Taylor, Charles. (1991). The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [3] Borgmann, Albert. (2006). Real American Ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [4] Turkle, Sherry. (2012). Alone Together. New York: Basic Books. [5] Willson, Michele. (2006). Technically Together. New York: Peter Lang. [6] See: Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone. New York: Simon & Schuster and Oldenburg, Ray. (1999). The Great Good Place. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. In my last post, I considered some of the consequences of instantly available and seemingly endless quantities of Internet-driven novelty for the good life, particularly in the areas of story and joke telling as well as how we converse and think about our lives. This week, I want to focus more on the challenges to willpower exacerbated by Internet devices. Particularly, I am concerned with how today’s generation of parents, facing their own particular limitations of will, may be encouraging their children to have a relationship with screens that might be best described as fetishistic. My interest is not merely with the consequences for learning, although psychological research does connect media-multitasking with certain cognitive and memory deficits. Rather, I am worried about the ways in which some technologies too readily seduce their users into distracted and fragmented ways of living rather than enhancing their capacity to pursue the good life.

A recent piece in Slate overviews much of recent research concerning the negative educational consequences of media multitasking. Unsurprisingly, students who allowed their focus to be interrupted by a text or some other digital task, whether in lecture or studying, perform significantly worse. The article, more importantly, notes the special challenge that digital devices pose to self-discipline, suggesting that such devices are the contemporary equivalent to the “marshmallow test.” The Stanford marshmallow experiment was a series of longitudinal studies that found children's capacity to delay gratification to be correlated with their later educational successes and body-mass index, among other factors. In the case of these experiments, children were rated according their ability to forgo eating a marshmallow, pretzel or cookie sitting in front of them in order to obtain two later on. Follow-up studies have shown that this capacity for self-discipline is likely as much environmental as innate; children in “unreliable environments,” where experimenters would make unrelated promises and then break them, exhibited a far lower ability to wait before succumbing to temptation. The reader may reasonably wonder at this point, what do experiments tempting children with marshmallows have to do with iPhones? The psychologist Roy Baumeister argues that the capacity to exert willpower behaves like a limited resource, generally declining after repeated challenges. By recognizing this aspect of human self-discipline, the specific challenge of device-driven novelty is clearer. Today, more and more time and effort must be expended in exerting self-control over various digital temptations, more quickly depleting the average person's reserves of willpower. Of course, there are innumerable non-digital temptations and distractions that people are faced with everyday, but they are of a decidedly different character. I can just as easily shirk by reading a newspaper. At some point, however, I run out of articles. The particular allure of a blinking email notice or instant message that always seems to demand one’s immediate attention cannot be discounted either. Although it is not yet clear what the broader effects of pervasive digital challenges to willpower and self-discipline will be, other emerging practices will likely only exacerbate the consequences. The portability of contemporary digital devices, for instance, has enabled the move from “TV as babysitter” to media tablet as pacifier. A significant portion of surveyed parents admit to using a smart phone or iPad in order to distract their children at dinners and during car rides. Parents, of course, should not bear all of the blame for doing so; they face their own limits to willpower due to their often hectic and stressful working lives. Nevertheless, this practice is worrisome not only because it fails to teach children ways of occupying themselves that do not involve staring into a screen but also since the device is being used foremost as a potentially pathological means of pacification. I have observed a number of parents stuffing a smart phone in their child’s face to prevent or stop a tantrum. While doing so is usually effective, I worry about the longer term consequences. Using a media device as the sole curative to their children’s’ emotional distress and anxiety threatens to create a potentially fetishistic relationship between the child and the technology. That is, the tablet or smart phone becomes like a security blanket – an object that allays anxiety; it is a security blanket, however, that the child does not have give up as he or she gets older. This sort of fetishism has already become fodder for cultural commentary. In the television show “The Office,” the temporary worker named Ryan generally serves as a caricature of the millennial generation. In one episode, he leaves his co-workers in the lurch during a trivia contest after being told he cannot both have his phone and participate. Forced to decide between helping his colleagues win the contest and being able to touch his phone, Ryan chooses the latter. This is, of course, a fictional example but, I think, not too unrealistic a depiction of the likely emotional response. I am unsure if many of the college students I teach would not feel a similar sort of distress if (forcibly) separated from their phones. This sort of affect-rich, borderline fetishistic, connection with a device can only make more difficult the attempt to live in any way other than by the device’s own logic or script. How easily can users resist the distractions emerging from a technological device that comes to double as their equivalent to a child’s security blanket? Yet, many of my colleagues would view my concerns about people’s capacities for self-discipline with suspicion. For those having read (perhaps too much) Michel Foucault, notions of self-discipline tend to be understood as a means for the state or some other powerful entity to turn humans into docile subjects. In seminar discussions, places like gyms are often viewed as sites of self-repression first and promoting of physical well-being second. There is, to be fair, a bit of truth to this. Much of the design of early compulsory schooling, for instance, was aimed at producing diligent office and factory workers who followed the rules, were able to sit still for hours and could tolerate both rigid hierarchies and ungodly amounts of tedium. Yet, just because the instilling of self-discipline can be convenient for those who desire a pacified populace does not mean it is everywhere and always problematic. The ability to work for longer than five minutes without getting distracted is a useful quality for activists and the self-employed to have as well; self-discipline is not always self-stultifying. Indeed, it may be the skill needed most if one is to resist the pull of contemporary forms of control, such as advertising. The last point is one of the critical oversights of many post-modern theorists. So concerned they are about forms of policing and discipline imposed by the state that they overlook how, as Zygmunt Bauman has also pointed out, humans are increasingly integrated into today’s social order through seduction rather than discipline, advertising rather than indoctrination. Fears about potentials for a 1984 can blind one to the realities of an emerging Brave New World. Being pacified by the equivalent of soma and feelies is, in my mind, no less oppressive than living under the auspices of Big Brother and the thought police. Viewed in light of this argument, the desire to “disconnect” can be seen not the result of an irrational fear of the digital but is made in recognition of the particular seductive challenges that it poses for human decision making. Too often, scholars and layperson alike tend to view technological civilization through the lens of “technological liberalism,” conceptualizing technologies as simply tools that enhance and extend the individual person’s ability to choose their own version of the good life. Insofar as a class of technologies increasingly enable users to give into their most base and unreflective proclivities – such as enabling endless distraction into a largely unimportant sea of videos, memes and trivia, they seem to enhance neither a substantive form of choice nor the good life. In a dark room sits a man at his computer. Intensely gazing at the screen, he lets the images and videos wash over him. He is on the hunt for just the right content to satisfy him. Expressing a demeanor of ennui alternating with short-lived arousal, he hurriedly clicks through pages, links and tabs. He is tired. He knows he should just get it over with and go to bed. Yet, each new piece of information is attention-grabbing in a different way and evokes a sense of satisfaction – small pleasures, however, tinged with a yearning for still more. At last, he has had enough. Spent. Looking at the clock, he cannot help but feel a little disappointed. Three hours? Where did all the time go? Somewhat disgusted with himself, he lies in bed and eventually falls asleep. This experience is likely familiar to many Internet users. The hypothetical subject that I described above could have been browsing for anything really: cat videos, pornography, odd news stories, Facebook updates or symptoms of a disorder he may or may not actually have. Through it, I meant to illustrate a common practice that one could call “novelty bingeing,” an activity that may not be completely new to the human condition but is definitely encouraged and facilitated by Internet technologies. I am interested in what such practices mean for the good life. However, there is likely no need for alarmism. The risks of chronic, technologically-supported pursuit of novelty and neophilia are perhaps more likely to manifest in a numbing sense of malaise than some dramatic crisis.

Nicholas Carr, of course, has already written a great deal about his worries that many of the informational practices enabled and encouraged in surfing the Internet may be making users shallower thinkers. Research at Stanford has confirmed that chronic media multitasking appears to have lasting, negative consequences on cognitive ability. Carr is concerned that Western humanity risks slowly and collectively forgetting how to do the kind of thinking seemingly better afforded by reading in one’s living room or walking in natural environments less shaped and infiltrated by industrial and digital technologies. To the extent that more linear and more meditative forms of mental activity are valuable for living well, typical Internet practices appear to stand in the way of the good life. One must, however, consider the trade-offs: Are the barriers to greater concentration and slower, meditative thinking worth the gains? Curiosity and neophilia are part of and parcel, in some sense, to intellectual activity writ large. Humans’ brains are attuned to novelty in order to help them understand their environments. On occasion, my own browsing of blogs and random articles has spurred thoughts that I may not have otherwise had, or at least at that moment. So it is not novelty-seeking, neophilia, in general that may be problematic for the practice of deep, broad thinking but the pursuit of decontextualized novelty for novelty’s sake. If the design of various contemporary Internet technologies can be faulted, it is for failing to provide a supporting structure for contextualizing novelty so that it does not merely serve as a pleasant distraction but also aids in the understanding of one’s own environment; in a sense, that responsibility, perhaps even burden, is shifted evermore onto users. Yet, to only consider the effects of Internet practices on cognitive capacities, I think, is to cast one’s net too narrowly. Where do affect and meaning fit into the picture? I think a comparison with practices of consumerism or materialistic culture is apt. As scholars such as Christopher Lasch have pointed out, consumerism is also driven by the endless pursuit of novelty. Yet, digital neophilia has some major differences; the object being consumed is an image, video or text that only exists for the consumer as long as it is visible on the screen or is stored on a hard-drive, and such non-material consumables seldom require a monetary transaction. It is a kind of consumerism without physical objects, a practice of consuming without purchasing. As a result, many of the more obvious “bads” of consumer behavior no longer applicable, such as credit card debt and the consumer’s feeling that their worth is dependent on their purchasing power. Baudrillard described consumerist behavior as the building up of a selfhood via a “system of objects.” That is, objects are valued not so much for their functional utility but as a collection of symbols and signs representing the self. Consumerism is the understanding of “being” as tantamount to “having” rather than “relating.” Digital neophilia, on the other hand, appears to be the building up of the self around a system of observations. Many heavy Internet users spend hours each day flitting from page to page and video to video; one shares in the spreading and viewing of memes in a way that parallels the sharing and chasing of trends in fashion and consumer electronics. Of which kind of “being” might such an immense investment of time and energy into pursuing endlessly-novel digital observations be in service? Unfortunately, I know of no one directly researching this question. I can only begin to surmise a partial answer from tangential pieces of evidence. The elephant of the room is whether such activity amounts to addiction and if calling it such aids or hinders our understanding of it. The case I mentioned in my last post, the fact that Evegny Morozov locks up his wi-fi card in order to help him resist the allure of endless novelty, suggests that at least some people display addictive behavior with respect to the Net. One of my colleagues, of course, would likely warn me of the risks in bandying about the word “addiction.” It has been often used merely to police certain forms of normality and pathologize difference. Yet, I am not convinced the word wholly without merit. Danah boyd, of all people, has worried that “we’re going to develop the psychological equivalent of obesity,” if we are not mindful concerning how we go about consuming digital content; too often we use digital technologies to pursue celebrity and gossip in ways that do not afford us “the benefits of social intimacy and bonding.” Nevertheless, the only empirical research I could find concerning the possible effects of Internet neophilia was in online pornography studies; research suggests that the viewing of endlessly novel erotica leads some men to devalue their partners in a way akin to how advertising might encourage a person to no longer appreciate their trusty, but outmoded, wardrobe. This result is interesting and, if the study is genuinely reflective of reality for a large number of men in committed relationships, worrisome.[1] At the same time, it may be too far a leap to extrapolate the results to non-erotic media forms. Does digital neophilia promote feelings of dissatisfaction with one’s proximate, everyday experiences because they fail to measure up with those viewed via online media? Perhaps. I generally find that many of my conversations with people my own age involve more trading of stories about what one has recently seen on YouTube than stories about oneself. I hear fewer jokes and more recounting of funny Internet skits and pranks, which tend to involve people no one in the conversation actually knows. Although social media and user-generated content has allowed more people to be producers of media, it is seems to have simultaneously amplified the consumption behavior of those who continue to not produce content. To me, this suggests that, at some level, many people are increasingly encouraged to think their lives are less interesting then what they find online. If they did not view online spaces as the final arbiters of what information is interesting or worthy enough to tell others, why else would so many people feel driven to tweet or post a status update any time something the least bit interesting happens to them but feel disinclined to proffer much of themselves or their own experiences in face-to-face conversation? I might be slightly overstating my case, but I believe the burden of evidence ought to fall on Internet-optimists. Novelty-bingeing may not be an inherent or essential characteristic of information technologies for all time, but, for the short-term, it is a dominant feature on the Net. The various harms may be subtle and difficult to measure, but it is evident in the obvious efforts of those seeking to avoid them – people who purchase anti-distraction software like “Freedom” or hide their wi-fi cards. The recognition of the consequences should not imply a wholesale abandonment of the Internet but merely to admit its current design failures. It should direct one’s attention to important and generally unexplored questions. What would an Internet designed around some conception of the good life not rooted in a narrow concern for the speed and efficiency of informational flows look like? What would it take to have one? [1] There are, clearly, other issues with using erotic media as a comparison. Many more socially liberal or libertarian readers may be ideologically predisposed to discount such evidence as obviously motivated by antiquated or conservative forms of moralism, countering that how they explore their sexuality is their own personal choice. (The psychological sciences be damned!) In my mind, mid-twentieth century sexual “liberation” eliminated some damaging and arbitrary taboos but, to too much of an extent, mostly liberated Westerners to have their sexualities increasingly molded by advertisers and media conglomerates. It has not actually amounted to the freeing the internally-developed and independently-derived individual sexuality for the purpose of self-actualization, as various Panglossian historical accounts would have one believe. As long as people on the left retreat to the rhetoric of individual choice, they remain blind to many of the subtle social processes by which sexuality is actually shaped, which are, in many ways, just as coercive as earlier forms of taboo and prohibition. Evgeny Morozov’s disclosure that he physically locks up his wi-fi card in order to better concentrate on his work spurred an interesting comment-section exchange between him and Nicholas Carr. At the heart of their disagreement is a dispute concerning the malleability of technologies, how this plasticity ought to recognized and dealt with in intelligent discourse about their effects and how the various social problems enabled, afforded or worsened by contemporary technologies could be mitigated. Neither mentions, however, the good life. Carr, though not ignorant of the contingency/plasticity of technology, tends to underplay malleability by defining a technology quite broadly and focusing mainly on their effects on his life and those of others. That is, he can talk about “the Net” doing X, such as contributing to increasingly shallow thinking and reading, because he is assuming and analyzing the Internet as it is presently constituted. Doing this heavy-handedly, of course, opens him up to charges of essentialism: assuming a technology has certain inherent and immutable characteristics. Morozov criticizes him accordingly: “Carr…refuses to abandon the notion of “the Net,” with its predetermined goals and inherent features; instead of exploring the interplay between design, political economy, and information science…” Morozov’s critique reflects the theoretical outlook of a great deal of STS research, particularly the approaches of “social construction of technology” and “actor-network theory.” These scholars hope to avoid the pitfalls of technological determinism – the belief that technology drives history or develops according to its own, and not human, logic – by focusing on the social, economic and political interests and forces that shape the trajectory of a technological development as well as the interpretive flexibility of those technologies to different populations. A constructivist scholar would argue that the Internet could have been quite different than it is today and would emphasize the diversity of ways in which it is currently used.

Yet, I often feel that people like Morozov often go too far and over-state the case for the flexibility of the web. While the Internet could be different and likely will be so in several years, in the short-term its structure and dynamics are fairly fixed. Technologies have a certain momentum to them. This means that most of my friends will continue to “connect” through Facebook whether I like the website or not. Neither is it very likely that an Internet device that aids rather than hinders my deep reading practices will emerge any time soon. Taking this level of obduracy or fixedness into account in one’s analysis is neither essentialism nor determinism, although it can come close. All this talk of technology and malleability is important because a scholar’s view of the matter tends to color his or her capacity to imagine or pursue possible reforms to mitigate many of the undesirable consequences of contemporary technologies. Determinists or quasi-determinists can succumb to a kind of fatalism, whether it be in Heidegger’s lament that “only a god can save us” or Kevin Kelly’s almost religious faith in the idea that technology somehow “wants” to offer human beings more and more choice and thereby make them happy. There is an equal level of risk, however, in overemphasizing flexibility in taking a quasi-instrumentalist viewpoint. One might fall prey to technological “solutionism,” the excessive faith in the potential of technological innovation to fix social problems – including those caused by prior ill-conceived technological fixes. Many today, for instance, look to social networking technologies to ameliorate the relational fragmentation enabled by previous generations of network technologies: the highway system, suburban sprawl and the telephone. A similar risk is the over-estimation of the capacity of individuals to appropriate, hack or otherwise work around obdurate technological systems. Sure, working class Hispanics frequently turn old automobiles into “Low Riders” and French computer nerds hacked the Minitel system into an electronic singles’ bar, but it would be imprudent to generalize from these cases. Actively opposing the materialized intentions of designers requires expertise and resources that many users of any particular technology do not have. Too seldom do those who view technologies as highly malleable ask, “Who is actually empowered in the necessary ways to be able to appropriate this technology?” Generally, the average citizen is not. The difficulty of mitigating fairly obdurate features of Internet technologies is apparent in the incident that I mentioned at the beginning of this post: Morozov regularly locks up his Internet cable and wi-fi card in a timed safe. He even goes so far as to include the screw-drivers that he might use to thwart the timer and access the Internet prematurely. Unsurprisingly, Carr took a lot of satisfaction in this admission. It would appear that some of the characteristics of the Internet, for Morozov, remain quite inflexible to his wishes, since he often requires a fairly involved system and coterie of other technologies in order to allay his own in-the-moment decision-making failures in using it. Of course, Morozov, is not what Nathan Jurgenson insultingly and dismissively calls a “refusenik,” someone refusing to utilize the Internet based on ostensibly problematic assumptions about addiction, or certain ascetic and aesthetic attachments. However, the degree to which he must delegate to additional technologies in order to cope with and mitigate the alluring pull of endless Internet-enabled novelty on his life is telling. Morozov, in fact, copes with the shaping power of Internet technologies on his moral choices as philosopher of technology Peter-Paul Verbeek would recommend. Rather than attempting to completely eliminate an onerous technology from his life, Morozov has developed a tactic that helps him guide his relationship with that technology and its effects on his practices in a more desirable direction. He strives to maximize the “goods” and minimize the “bads.” Because it otherwise persuades or seduces him into distraction, feeding his addiction to novelty, Morozov locks up his wi-fi card so he can better pursue the good life. Yet, these kinds of tactics seem somewhat unsatisfying to me. It is depressing that so much individual effort must be expended in order to mitigate the undesirable behaviors too easily afforded or encouraged by many contemporary technologies. Evan Selinger, for instance, has noted how the dominance of electronically mediated communication increasingly leads to a mindset in which everyday pleasantries, niceties and salutations come to be viewed as annoyingly inconvenient. Such a view, of course, fails to recognize the social value of those seemingly inefficient and superfluous “thank you’s” and “warmest regards’.” Regardless, Selinger is forced to do a great deal more parental labor to disabuse his daughter of such a view once her new iPod affords an alluring and more personally “efficient” alternative to hand-writing her thank-you notes. Raising non-narcissistic children is hard enough without Apple products tipping the scale in the other direction. Internet technologies, of course, could be different and less encouraging of such sociopathological approaches to etiquette or other forms of self-centered behavior, but they are unlikely to be so in the short-term. Therefore, cultivating opposing behaviors or practicing some level of avoidance are not the responses of a naïve and fearful Luddite or “refusenik” but of someone mindful of the kind of life they want (or want their children) to live pursuing what is often the only feasible option available. Those pursuing such reactive tactics, of course, may lack a refined philosophical understanding of why they do what they do, but their worries should not be dismissed as naïve or illogically fearful simply because they struggle to articulate a sophisticated reasoning. Too little attention and too limited of resources are focused on ways to mitigate declines in civility or other technological consequences that ordinary citizens worry about and the works of Carr and Sherry Turkle so cogently expose. Too often, the focus is on never-ending theoretical debates about how to “properly” talk about technology or forever describing all the relevant discursive spaces. More systematically studying the possibilities for reform seems more fruitful than accusations that so-and-so is a “digital dualist,” a charge that I think has more to do with the accused viewing networked technologies unfavorably than their work actually being dualistic. Theoretical distinctions, of course, are important. Yet, at some point neither scholarship nor the public benefits from the linguistic fisticuffs; it is clearly more a matter of egos and the battle over who gets to draw the relevant semantic frontier, outside of which any argument or observation can be considered too insufficiently “nuanced” to be worthy of serious attention. Regardless, barring the broader embrace of systems of technology assessment and other substantive means of formally or informally regulating technologies, some concerned citizen respond to tendency of many contemporary technologies to fragment their lives or distract them from the things they value by refusing to upgrade their phones or unplugging their TVs. Only the truly exceptional, of course, lock them in safes. Yet, the avoidance of technologies that encourage unhealthy or undesirable behaviors is not the sign of some cognitive failing; for many people, it beats acquiescence, and technological civilization currently provides little support for doing anything in between. The current job market is tough, especially for recent college graduates with limited experience. The unemployment and underemployment rate for twenty-somethings is around 53%. Many who are employed work jobs for which they are overqualified. My wife, for example, has a master’s degree in Biotechnology and several years experience but works part-time for fifteen dollars an hour with no benefits as a laboratory technician. It increasingly appears that most job growth is occurring in low-skilled and low-paying positions. Some rise in the demand for highly skilled technical positions, however, suggests not a rising tide but a job market becoming more and more polarized in terms of both skill level and wages.