|

It is an understatement to say that the case of Anna Stubblefield is simply controversial. Opinions of the former Rutgers professor, who was recently sentenced to some 10 odd years in prison for the charge of sexually assaulting a disabled man, are highly polarized. When reading comments on recent news stories on the case, one finds not only people who find her absolutely abhorrent but also people who empathize or support her side. No doubt there are important issues to consider regarding the rights of disabled persons, professional ethics, racism, and the nature of consent. However, I want to focus on how the framing of the case as a battle between science and pseudoscience prevents us from sensibly dealing with the politics underlying the issue. The case is strongly shaped by a broader dispute over of the scientific status of “facilitated communication” (FC), a technique claimed by its advocates to allow previously voiceless people with cerebral palsy or autism to speak. As its name suggests, a facilitator helps guide the disabled person’s hand to a keyboard. In the most favorable reading of the practice, the facilitator simply balances out the muscle contractions and lessens the physical barriers to typing. Some see the practice, however, as more than mere assistance: they claim that the facilitator is the one really doing the typing, either consciously or unconsciously. In the former case, FC is a wonderful gift for those suffering from disabilities and their families. In latter reading, facilitators are charlatans, utilizing a pseudoscientific technique to deceive people. "Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations." This latter view seems to have won out in the case of Anna Stubblefield, who claims that DJ--a man with profound physical and suspected mental disabilities—consented to have sex with her via FC. The court rules that FC did not meet the state standards for science. Hence, Stubblefield was unable to mount a much of a defense vis-à-vis FC.

Most people fail to grasp, however, exactly how hard it is to distinguish science and pseudoscience—despite whatever popularizers like Neil DeGrasse Tyson or Bill Nye seem to claim. Science does not simply produce unquestionable facts, rather it is a skilled practice; its capacity to prove truth is always partial, seen far better in hindsight than in the moment. As science and technology studies scholars well illustrate, experiments are incredibly complex—only becoming more so when their results are controversial. The fact that many scientific activities are heavily dependent on the skill of the scientist is on the one hand obvious, but nevertheless eludes most people. Mid-20th century experiments attempting to transfer memories (e.g., fear of the dark, how to run a maze) between planarian worms or mice exemplify this facet of science. Skeptical and supportive scientists went back and forth incessantly over methodological disagreements in trying to determine whether the observed effects were “real,” eventually considering more than 70 separate variables as possible influences on the outcome of memory transfer experiments. Even though some skeptical scientists derided skill-based variables as a so-called “golden hands” argument, there are plenty of areas of science where an experimentalist’s skill makes or breaks an experiment. Biologists, in particular, frequently lament the difficulty of keeping an RNA sample from breaking down or find themselves developing fairly eccentric protocols for getting “good” results out of a Western Blot or bioassay experiment. What some will view as ad-hoc “golden hands” excuses are often simply facets of doing a complex and highly sensitive procedure. A similar dispute over the role of the skill of the practitioner makes FC controversial. After rosy beginnings, skeptical scientists produced results that cast doubt on the technique. Experiments involved the attempt to duplicate text generated with the help of a disabled person’s usual facilitator with a “naïve” facilitator or the asking of questions to which the facilitator wouldn’t know the answer. Indeed, just such an experiment was conducted with DJ, for which both sides claimed victory (Jeff McMahan and Peter Singer, for instance, argue that DJ is more cognitively able than the prosecution would have one believe). As has been the case for other controversial scientific phenomenon, FC only becomes more complex the more deeply one looks into it. Advocates of the method raise their own doubts about studies claiming to disprove the technique’s effectiveness, contending that facilitation requires skills and sensitivities unique to the person being facilitated and that the stressfulness of the testing environment skews the results in the favor of skeptics. There is enough uncertainty surrounding the abilities of those with autism or cerebral palsy to make reasonable arguments either way. Given our inability to see into the minds of people so disabled, both sides of the debate end up speaking for them in light of indirect observations. Again, my point is not to try to argue one way or another for FC but to merely point out that the phenomenon under consideration is immensely complex; we simplify it only at our peril. Indeed, the history of science and technology provides plenty of evidence suggesting that we are better off acknowledging that even today’s best science is unlikely to provide sure answers to a controversial debate. Advocates of nuclear energy, for instance, once claimed that their science proved that an accident was a near impossibility, happening perhaps once in ten thousand years. Similarly, some petroleum geology experts have claimed that it is physically impossible for fracking to introduce natural gas and other contaminants to water supplies: there is simply too much rock in between. Yet, an EPA scientist has recently produced fairly persuasive evidence to the contrary. “Settled science” rhetoric has mainly served to shut down inquiry, and the discovery of contrary findings in ensuing decades only adds support to the view that reaching something like scientific certainty is a long and difficult struggle. As a result, scientific controversies are often as much settled politically as scientifically: they are as much battles of rhetoric as facts. Rather than pretend that absolute certitude were possible, what if we proceeded with controversial practices like FC guided by the presumption that we might be wrong about it? What if we assumed that it was possible the method could work—perhaps for a very small percentage of autistics and those born with severe cerebral palsy--but that we are challenged in our ability to know for whom it worked? Moreover, self-deception—like many believe Anna Stubblefield fell prey to—remains a pervasive risk. The situation changes dramatically. Rather than commit oneself to idea that something is either pure truth or complete pseudoscience, the issue can be framed in terms of risk: given that we may be wrong, who might suffer which benefits and harms? How many cases of sham communication via FC balances out the possibility of a non-communicative person losing their voice? In other words, do we prefer false positives or false negatives? Such a perspective challenges people to think more deeply about what matters with respect to FC. Surely the prospect of disabled people being abused or killed because of communication that originates more with the facilitator than the person being facilitated is horrifying. Yet, on the other hand, Daniel Engeber describes meeting families who feel like FC has been a godsend. Even in the scenario in which FC only provides a comforting delusion, is anyone being harmed? A philosophy professor I once knew remarked that he’d take a good placebo over nothing at all any day of the week. On what grounds do we have to deprive people of controversial (even potentially fictitious) treatment if it is not too harmful and potentially increases the well-being of at least some of the people involved? I don’t have an answer to these questions, but I do know that we cannot begin to debate them if we hide behind a simplistic partitioning of all knowledge into either science or pseudoscience, pretending that such designations can do our politics for us When reading some observer's diagnoses of what ails the United States, one can get the impression that Americans are living in an unprecedented age of public scientific ignorance. There is reason, however, to wonder if people today are really any more ignorant of facts like water boiling at lower temperatures at higher altitudes or if any more people believe in astrology than in the past. According to some studies, Americans have never been more scientifically literate. Nevertheless, there is no shortage of hand-wringing about the remaining degree of public scientific illiteracy and what it might mean for the future of the United States and American democracy. Indeed, scientific illiteracy is targeted as the cause of the anti-vaccination movement as well as opposition to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and nuclear power. However, I think such arguments misunderstand the issue. If America has a problem with regard to science, it is not due to a dearth of scientific literacy but a decline in science's public legitimacy.

The thinking underlying worries about widespread scientific illiteracy is rooted in what is called the “deficit model.” In the deficit model, the cause of the discrepancy between the beliefs of scientists and those are the public is, in the words of Dietram Scheufele and Matthew Nisbet, a “failure in transmission.” That is, it is believed that negligence of the media to dutifully report the “objective” facts or the inability of an irrational public to correctly receive those facts prevents the public from having the “right” beliefs regarding issues like science funding or the desirability of technologies like genetically modified organisms. Indeed, a blogger for Scientific American blames the opposition of liberals to nuclear power on “ignorance” and “bad psychological connections.” It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to say that the deficit model depicts anyone who is not a technological enthusiast as uninformed, if not idiotic. Regardless of whether or not the facts regarding these issues are actually “objective” or totally certain (both sides dispute the validity of each other’s arguments on scientific grounds), it remains odd that deficit model commentators view the discrepancy between scientists’ and the public’s views on GMOs and other issues as a problem for democracy. Certainly they are correct that it is preferable to have a populace that can think critically and suffers from few cognitive impairments to inquiry when it comes to wise public decision making. Yet, the idea that, when properly “informed” of the relevant facts, scientifically literate citizens would immediately agree with experts is profoundly undemocratic: It belittles and erases all the relevant disagreements about values and rights. Such a view ignores, for instance, the fact that the dispute over GMO labeling has as much to do with ideas about citizens’ right to know and desire for transparency as the putative safety of GMOs. By acting as if such concerns do not matter – that only the outcome of recent safety studies do – the people sharing those concerns are deprived of a voice. The deficit model inexorably excludes those not working within a scientistic framework from democratic decision making. Given the deficit model’s democratic deficits as well as the lack of any evidence that scientific illiteracy is actually increasing, advocates of GMOs and other potentially risky instances of technoscience ought to look elsewhere for the sources of public scientific controversy. If anything has changed in the last decades it is that science and technology have less legitimacy. Indeed, science writers could better grasp this point by reading one of their own. Former Discover writer Robert Pool notes that the point of legal and regulatory challenges to new technoscience is not simply to render it safer but also more acceptable to citizens. Whether or not citizens accept a new technology depends upon the level of trust they have of technical experts (and the firms they work for). Opposition to GMOs, for instance, is partly rooted in the belief that private firms such as Monsanto cannot be trusted to adequately test their products and that the FDA and EPA are too toothless (or captured by industry interests) to hold such companies to a high enough standard. Technoscientists and cheerleading science writers are probably oblivious to the workings and requirements for earning public trust because they are usually biased to seeing new technologies as already (if not inherently) legitimate. Those deriding the public for failing to recognize the supposedly objective desirability of potentially risky technology, moreover, have fatally misunderstood the relationship between expertise, knowledge, and legitimacy. It is unreasonable to expect members of the public to somehow find the time (or perhaps even the interest) to learn about the nuances of genetic transmission or nuclear safety systems. Such expectations place a unique and unfair burden on lay citizens. Many technical experts, for instance, might be found to be equally ignorant of elementary distinctions in the social sciences or philosophy. Yet, few seem to consider such illiteracies to be equally worrisome barriers to a well-functioning democracy. In any case, as political scientists Joseph Morone and Edward Woodhouse argue, the position of the public is not to evaluate complex or arcane technoscientific problems directly but to decide which experts to trust to do so. Citizens, according to Morone and Woodhouse, were quite reasonable to turn against nuclear power when overoptimistic safety estimates were proven wrong by a series of public blunders, including accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, as well as increasing levels of disagreement among experts. Citizens’ lack of understanding of nuclear physics was beside the point: The technology was oversold and overhyped. The public now had good grounds to believe that experts were not approaching nuclear energy or their risk assessments responsibly. Contrary to the assumptions of deficit modelers, legitimacy is not earned simply through technical expertise but via sociopolitical demonstrations of trustworthiness. If technoscientific experts were to really care about democracy, they would think more deeply about how they could better earn legitimacy in the eyes of the public. At the very least, research in science and technology studies provides some guidance on how they ought not to proceed. For example, after post-Chernobyl accident radiation rained down on parts of Cumbria, England, scientists quickly moved in to study the effects as well as ensure that irradiated livestock did not get moved out of the area. Their behavior quickly earned them the ire of local farmers. Scientists not only ignored the relevant expertise that farmers had regarding the problem but also made bold pronouncements of fact that were later found to be false, including the claim that the nearby Sellafield nuclear processing plant had nothing to do with local radiation levels. The certainty with which scientists made their uncertain claims as well as their unwillingness to respond to criticism by non-scientists led farmers to distrust them. The scientists lost legitimacy as local citizens came to believe that they were sent there by the national government to stifle inquiry into what was going on rather than learn the facts of the matter. Far too many technoscientists (or at least their associated cheerleaders in popular media) seem content to repeat the mistakes of these Cumbrian radiation scientists. “Take your concerns elsewhere. The experts are talking,” they seem to say when non-experts raise concerns, “Come back when you’ve got a science degree.” Ironically (and tragically), experts’ embrace of deficit model understandings of public scientific controversies undermines the very mechanisms by which legitimacy is established. If the problem is really a deficit of public trust, diminishing the transparency of decisions and eliminating possibilities for citizen participation is self-defeating. Anything looking like a constructive and democratic resolution to controversies like GMOs, fracking, or nuclear energy is only likely to happen if experts engage with and seek to understand popular opposition. Only then can they begin to incrementally reestablish trust. Insofar as far too many scientists and other experts believe they deserve public legitimacy simply by their credentials – and some even denigrate lay citizens as ignorant rubes – public scientific controversies are likely to continue to be polarized and pathological. Looking upon all the polarized rhetoric concerning vaccines, GMO crops, climate change, and processed foods one might be tempted to conclude that the American status quo is under attack by a fervent anti-science movement. Indeed, it is not hard to find highly educated and otherwise intelligent people making just that claim in popular media. To some, that proposition probably seems commonsensical if not blatantly obvious. Why else would people be skeptical of all these advances in medical, climate, and agricultural sciences? However, looking more closely at the style of argumentation utilized by critics undermines the claim that they are “anti-science.” Rather, if there is any bias to popular deliberation regarding the risks regarding vaccines, climate change, and GMO crops it is a widespread allergy to engaging in political talk about values.

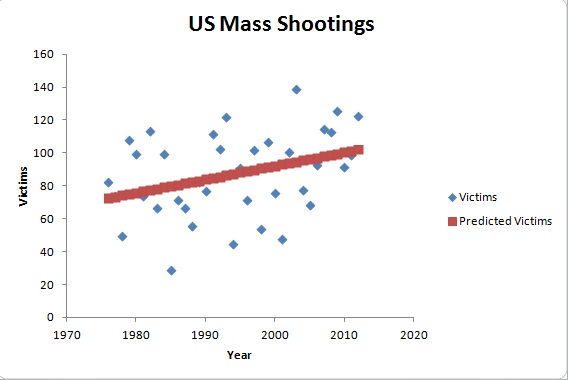

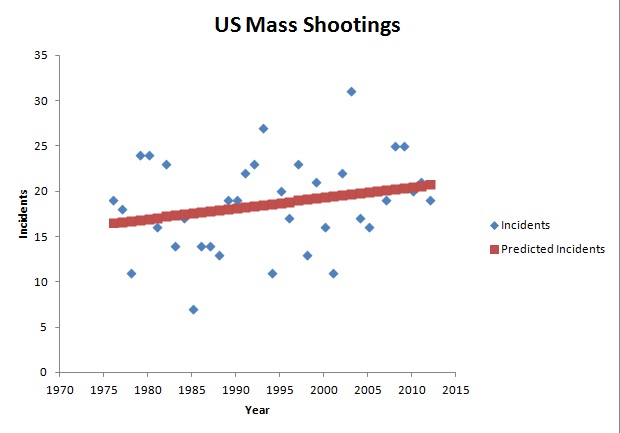

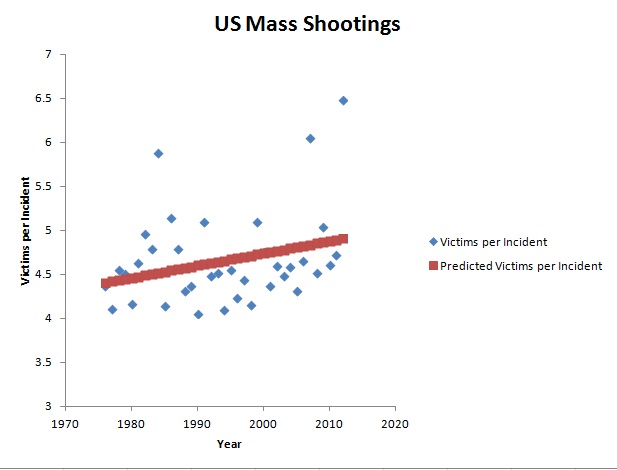

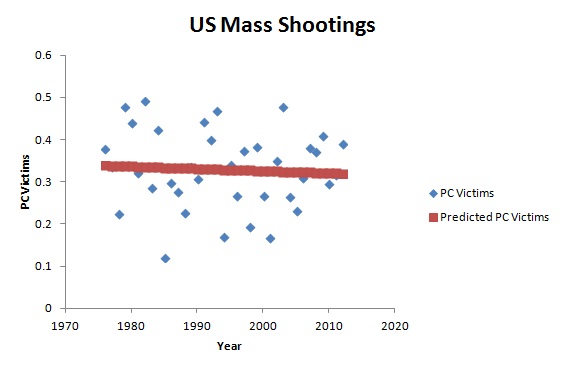

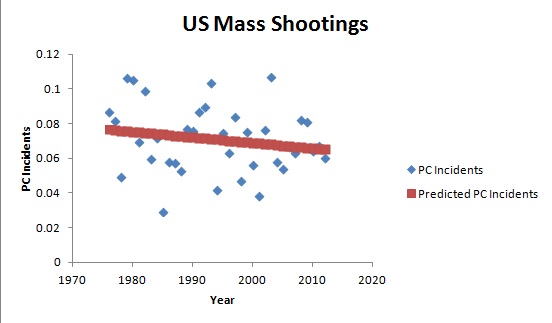

Consider Vani Hari, aka “Food Babe.” Her response to a take-down piece in Gawker is filled with references to studies and links to groups like Consumers Union, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Environmental Working Group, who do employ people with scientific credentials and conduct tests. Groups concerned with potential adverse affects from vaccines, similarly, have their own scientists to fall back on and draw upon highly skeptical and scientific language to highlight uncertainties and as-of-yet undone studies that might help settle safety concerns. If opponents were truly anti-science, they would not exert so much effort to mobilize scientific rhetoric and expertise. Of course, there is still the question of whose expertise is or should be relevant as well as whether or not participants in the debate are attempting a fair and charitable interpretation of available evidence. Nevertheless, the claim that the debate is a result of a split between pro and anti-science factions is pretty much incoherent, if not deluded. Contrary to recurring moral panics about the supposed emergence of polarized anti-scientism, American scientific controversies are characterized by a surprising amount of agreement. No one seems to be in disagreement over the presumption that debate about GMO crops, vaccines, processed foods, and other controversial instances of technoscience should be settled by scientific facts. Even creationists have leaned heavily on a scientific-sounding use of information theory to try to legitimate so-called “intelligent design.” Regardless, this agreement, in turn, rests on an unquestioned assumption that these are even issues that can be settled by science. Both the pro and the con sides are in many ways radically pro-science. Because of this pervasive and unstated agreement, the very real value disagreements that drive these controversies are left by the wayside in favor of endless quibbling over what “the facts” really are. Given the experimenter’s regress, the reality that experimental tests and theories are wrought with uncertainties and unforeseen complexities but are nevertheless relied upon to validate each other, there is always some room for both doubt and confirmation bias in nearly all scientific findings. Of course, doubt is usually mobilized selectively by each side in controversies in ways that mirror their underlying value commitments. Those who tend to view developments within modern science as almost automatically amounting to human progress inevitably find some way to depict opponents as out of touch with the scientific method or using improper methodology. Critics of GMOs or pesticides, for their part, routinely claim to find similar inadequacies in existing safety studies. Additional scientific research, moreover, often only uncovers additional uncertainties; more science can just as often make controversies even more intractable. Therefore, I think that Americans would be better off if social movements were more anti-science. Of course, I do not mean that they would totally disavow the benefits of looking at things scientifically or the more unambiguous benefits of contemporary technoscience. Instead, what I mean is that such groups would reject the assumption that all issues should be viewed, first and foremost, scientistically. Underneath most, if not all, public scientific controversies are real disagreements that relate to values and power. Vaccine critics, rightly or wrongly, are motivated by concerns about a felt loss of liberty regarding their abilities to make health decisions for their children in an age of seemingly pervasive risk. Advocates for more organic farming and fewer petroleum-derived residues on their food and in eco-systems are not only concerned about health risks but the lack of input they have regarding what goes into the products they ingest. The real debate should concern to what extent the technoscientific experts who create the potentially risky and nearly unavoidable products that fill our houses, break down into our local watersheds, and end up in our bloodstreams (along with their allies in business and government) are sufficiently publically accountable. Advocacy groups, however, are caught in a Catch-22. As long as the main legitimacy-imparting public language is scientistic, those who fill their discourse primarily with a consideration of values will probably have a hard time getting heard. Nevertheless, incremental gains could be had if at least some people endeavored to talk to friends, family, and acquaintances about these matters differently: in more explicitly political ways. Those who support mandatory vaccination would do better to talk about the rights of parents of infants and the elderly to not have worry under the specter of previously eradicated and potentially deadly diseases than to claim a level of certitude about vaccine risk they cannot possibly possess. Advocates of organic farming would do well to frame their opposition to GMOs with reference to questions concerning who owns the means of producing food, who primarily benefits, and who has the power to decide which agricultural products are safe. Far too many citizens talk as if they believe science can do their politics for them. It is about time we put that belief to rest. If you have been on NY Magazine's "Science of Us" blog during the last two days, you might have seen this graph along with the conclusion that mass shootings in the United States are not on the rise: The author looks at the graph, shrugs their shoulders and concludes "It's clear that there is no major upward trend." It has been quite a few years since I was a math student but this struck me as odd. Most strange is that, for a science blog, they should know that one does not analyze data simply by looking at it but with statistics. Posting this graph without analysis is both lazy and potentially dishonest. I went ahead did a linear regression on the linked raw data: Despite the apparent scatter, there is actually an average trend upward. The increase is statistically significant for victims at a 95% confidence but for the number of incidents the relationship is not as certain (85%). So, although the data does not provide a super strong case for incidents being on the rise, it does suggest that the number of victims are. So, let's look at the number of victims per incident: Indeed, there is an upward average trend for victims per incident (90% confidence). Moreover, one can see that the two most deadly years were in the last decade. So, far from simply being a product of an "availability heuristic" (perception of increase just based on more media coverage), it seems plausible that mass shooting victimization is on the rise. Of course, if one subtracted the outlier years, the relationship would likely weaken somewhat. However, the above analysis is based on the absolute numbers of incidents and victims. What about the per capita figures? The best fit lines from the linear regression when the number of victims and incidents are divided by the United State's population figures seem to suggest a flat or downward trend in the per capita rates of mass shooting incidents and victims. However, for both cases the relationship is NOT statistically significant.

This analysis took all of about twenty minutes to do in Excel and resulted in conclusions very different from those offered by the Science for Us blog. The data suggests that there are more victims and incidents today than in previous decades, though that fact is probably more related to the growth in the US population than an increased propensity toward mass shootings. However, it does seem that mass shootings have been (on average) getting more and more deadly. Nevertheless, one should not lose sight of the fact that these events have not declined along with the firearm homicide rates and could still be considered to occur far more frequently than is desirable. Motivation for sensible gun control measures and other changes to public policy does not rely on discovering a growing epidemic in the data but simply the belief that such needless violence could be prevented. Research continues to suggest that lax regulations combined with a strong "gun culture" contributes significantly to America's incredibly high rate of firearm related crime (compared to other countries). Gun violence, of course, is a complex issue that I think is not simply solved by restricting access but also providing better economic and political opportunities to those Americans more likely to be both the perpetrators and victims of gun violence (e.g., poor minorities). Furthermore, it is not just a civilian issue, police in this country shoot and kill far more citizens than other countries and are increasingly militarized to boot. Regardless, I will save a more in-depth analysis of gun violence for another post. 5/26/2014 Are These Shoes Made for Running? Uncertainty, Complexity and Minimalist FootwearRead Now Repost from Technoscience as if People Mattered In almost every technoscientific controversy participants could take better account of the inescapable complexities of reality and the uncertainties of their knowledge. Unfortunately, many people suffer from significant cognitive barriers that prevent them from doing so. That is, they tend to carry the belief that their own side is in unique possession of Truth and that only their opponents are in any way biased, politically motivated or otherwise lacking in sufficient data to support their claims. This is just as clear in the case of Vibram Five Finger shoes (i.e., “toe shoes”) as it is for GMO’s and climate change. Much of humanity would be better off, however, if technological civilization responded to these contentious issues in ways more sensitive to uncertainty and complexity. Five Fingers are the quintessential minimalist shoe, receiving much derision concerning its appearance and skepticism about its purported health benefits. Advocates of the shoes claim that its minimalist design helps runners and walkers maintain a gait similar to being barefoot while enjoying protection from abrasion. Padded shoes, in contrast, seem to encourage heel striking and thereby stronger impact forces in runners’ knees and hips. The perceived desirability of a barefoot stride is in part based on the argument that it better mimics the biomechanical motion that evolved in humans over millennia and the observation of certain cultures that pursue marathon long-distance barefoot running. Correlational data suggests that people in places that more often eschew shoes suffer less from chronic knee problems, and some recent studies find that minimalist shoes do lead to improved foot musculature and decreased heel striking. Opponents, of course, are not merely aesthetically opposed to Five Fingers but mobilize their own sets of scientific facts and experts. Skeptics cite studies finding higher rates of injury among those transitioning to minimalist shoes than those wearing traditional footwear. Others point to “barefoot cultures” that still run with a heel striking gait. The recent settlement by Vibram with plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit, moreover, seems to have been taken as a victory of rational minds over pseudoscience by critics who compare the company to 19th century snake oil salesmen. Yet, this settlement was not an admission that the shoes did nothing but merely that recognition that there are not yet unequivocal scientific evidence to back up the company’s claims about the purported health benefits of the shoes.

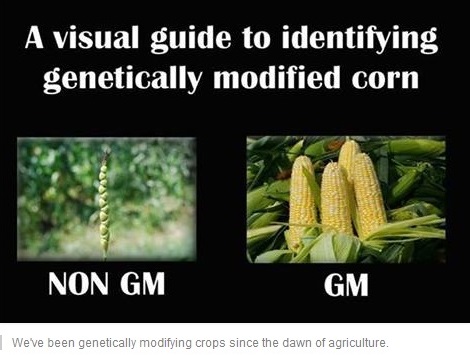

Neither of the positions, pro or con, is immediately more “scientific” than the other. Both sides use value-laden heuristics to take a position on minimalist shoes in the absence of controlled, longitudinal studies that might settle the facts of the matter. The unspoken presumption among critics of minimalist shoes is that highly padded, non-minimalist shoes are unproblematic when really they are an unexamined sociotechnical inheritance. No scientific study has justified adding raised heels, pronation control and gel pads to sneakers. Advocates of minimalist shoes and barefoot running, on the other hand, trust the heuristic of “evolved biomechanics” and “natural gait” given the lack of substantial data on footwear. They put their trust in the argument that humans ran fine for millenia without heavily padded shoes. There is nothing inherently wrong, of course, about these value commitments. In everyday life as much as in politics, decisions must be made with incomplete information. Nevertheless, participants in debates over these decisions too frequently present themselves as in possession of a level of certainty they cannot possibly have, given that the science on what kinds of shoes humans ought to wear remains mostly undone. At the same time, it seems unfair to leave footwear consumers in the position of having to fumble with the decision between purchasing a minimalist or non-minimalist shoe. A technological civilization sensitized to uncertainty and complexity would take a different approach to minimalist shoes than the status quo process of market-led diffusion with very little oversight or monitoring. To begin, the burden of proof would be more appropriately distributed. Advocates of minimalist shoes are typically put in the position of having to prove the safety and desirability of them, despite the dearth of conclusive evidence whether or not contemporary running shoes are even safe. There are risks on both sides. Minimalist shoes may end up injuring those who embrace them or transition too quickly. However, if they do in fact encourage healthier biomechanics, it may be that multitudes of people have been and continue to be unnecessarily destined for knee and hip replacements by their clunky New Balances. Both minimalist and non-minimalist shoes need to be scrutinized. Second, use of minimalist shoes should be gradually scaled-up and matched with well-funded, multipartisan monitoring. Simply deploying an innovation with potential health benefits and detriments then waiting for a consumer response and, potentially, litigation means an unnecessarily long, inefficient and costly learning process. Longitudinal studies on Five Fingers and other minimalist shoes could have begun as soon as they were developed or, even better, when companies like Nike and Reebok started adding raised heels and gel pads. Monitoring of minimalist shoes, moreover, would need to be broad enough to take account of confounding variables introduced by cultural differences. Indeed, it is hard to compare American joggers to barefoot running Tarahumara Indians when the former have typically been wearing non-minimalist shoes for their whole lives and tend to be heavier and more sedentary. Squat toilets make for a useful analogy. Given the association of western toilets with hiatal hernias and other ills, abandoning them would seem like a good idea. However, not having grown up with them and likely being overweight or obese, many Westerners are unable to squat properly, if at all, and would risk injury using a squat toilet. Most importantly, multi-partisan monitoring would help protect against clear conflicts of interest. The controversy over minimalist and non-minimalist shoes impacts the interests of experts and businesses. There is a burgeoning orthotics and custom running shoes industry that not only earns quite a lot of revenue in selling special footwear and inserts but also certifies only certain people as having the “correct” expertise concerning walking and running issues. They are likely to adhere to their skepticism about minimalist shoes as strongly as oil executives do on climate change, for better or worse. Although large firms are quickly introducing their own minimalist shoes designs, a large-scale shift toward them would threaten their business models: Since minimalist shoes do not have cushioning that breaks down over time, there is no need to replace them every three to six months. Likewise, Vibram itself is unlikely to fully explore the potential limitations of their products. Finally, funds should have been set aside for potential victims. Given a long history of unintended consequences resulting from technological change, it should not have come as a surprise that a dramatic shift in footwear would produce injuries in some customers. Vibram Five Finger shoes, in this way, are little different from other innovations, such as the Toyota Prius’ electronically controlled accelerator pedal or novel medications like Vioxx. Had Vibram been forced to proactively set aside funds for potential victims, they would have been provided an incentive to more carefully study their shoes’ effects. Moreover, those ostensibly injured by the company’s product would not have to go through such a protracted and expensive legal battle to receive compensation. Although the process I have proposed might seem strange at first, the status quo itself hardly seems reasonable. Why should companies be permitted to introduce new products with little accountability for the risks posed to consumers and no requirements to discern what risks might exist? There is no obvious reason why footwear and sporting equipment should not be treated similarly to other areas of innovation where the issues of uncertainty and complexity loom large, like nanotechnology or new pharmaceuticals. The potential risks for acute and chronic harms are just as real, and the interests of manufacturers and citizens are just as much in conflict. Are Vibram Five Finger shoes made for running? Perhaps. But without changes to the way technological civilization governs new innovations, participants in any controversy are provided with neither the means nor sufficient incentive to find the answer. 5/5/2014 Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid: Continuity Arguments and Controversial TechnoScienceRead Now Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Far too much popular media and opinion is directed toward getting people to “Drink the Kool-Aid” and uncritically embrace controversial science and technology. One tool from Science and Technology Studies (STS) toolbox that can help prevent you from too quickly taking a swig is the ability to recognize and take apart continuity arguments. Such arguments take the form: Contemporary practice X shares some similarities with past practice Y. Because Y is considered harmless, it is implied that X must also be harmless. Consider the following meme about genetically modified organisms (GMO’s) from the "I Fucking Love Science" Facebook feed: This meme is used to argue that since selective breeding leads to the modification of genes, it is not significantly distinct from altering genetic code via any other method. The continuity of “modifying genetic code” from selective breeding to contemporary recombinant DNA techniques is taken to mean that the latter is no more problematic than the former. This is akin to arguing that exercise and proper diet is no different from liposuction and human-growth-hormone injections: They are all just techniques for decreasing fat and increasing muscle, right?

Continuity arguments, however, are usually misleading and mobilized for thinly veiled political reasons. As certain technology ethicists argue, “[they are] often an immunization strategy, with which people want to shield themselves from criticism and to prevent an extensive debate on the pros and cons of technological innovations.” Therefore, it is unsurprising to see continuity arguments abound within disagreements concerning controversial avenues of scientific research or technological innovation, such as GMO crops. Fortunately for you dear reader, they are not hard to recognize and tear apart. Here are the three main flaws in reasoning that characterize most continuity arguments. To begin, continuity arguments attempt to deflect attention away from the important technical differences that do exist. Selective breeding, for example, differs substantively from more recent genetic modification techniques. The former mimics already existing evolutionary processes: The breeder artificially creates an environmental niche for certain valued traits ensure survival by ensuring the survival and reproduction of only the organisms with those traits. Species, for the most part, can only be crossed if they are close enough genetically to produce viable offspring. One need not be an expert in genetic biology to recognize how the insertion of genetic material from very different species into another via retroviruses or other techniques introduces novel possibilities, and hence new uncertainties and risks, into the process. Second, the argument presumes that the past technoscientific practices being portrayed as continuous with novel ones are themselves unproblematic. Although selective breeding has been pretty much ubiquitous in human history, its application has not been without harm. For instance, those who oppose animal cruelty often take exception to the creation, maintenance and celebration of “pure” breeds. Not only does the cultural production of high status, expensive pedigrees provide a financial incentive for “puppy mills” but also discourages the adoption of mutts from shelters. Moreover, decades or centuries of inbreeding have produced animals that needlessly suffer from multiple genetic diseases and deformities, like boxers that suffer from epilepsy. Additionally, evidence is emerging that historical practices of selective breeding of food crops has rendered many of them much less nutritious. This, of course, is not news to “foodies” who have been eschewing iceberg lettuce and sweet onions for arugula and scallions for years. Regardless, one need not look far to see that even relatively uncontroversial technoscience has its problems. Finally and most importantly, continuity arguments assume away the environmental, social, and political consequences of large-scale sociotechnical change. At stake in the battle over GMO’s, for instance, are not only the potential unforeseen harms via ingestion but also the probable cascading effects throughout technological civilization. There are worries that the overliberal use of pesticides, partially spurred by the development of crops genetically modified to be tolerant of them, is leading to “superweeds” in the same way that the overuse of antibiotics lead to drug-resistant “superbugs.” GMO seeds, moreover, typically differ from traditional ones in that they are designed to “terminate” or die after a period of time. When that fails, Monsanto sues farmers who keep seeds from one season to the next. This ensures that Monsanto and other firms become the obligatory point of passage for doing agriculture, keeping farmers bound to them like sharecroppers to their landowner. On top of that, GMO’s, as currently deployed, are typically but one piece of a larger system of industrialized monoculture and factory farms. Therefore, the battle is not merely about the putative safety of GMO crops but over what kind of food and farm culture should exist: One based on centralized corporate power, lots of synthetic pesticides, and high levels of fossil fuel use along with low levels of biodiversity or the opposite? GMO continuity arguments deny the existence of such concerns. So the next time you hear or read someone claim that some new technological innovation or area of science is the same as something from the past: such as, Google Glasses not being substantially different from a smartphone or genetically engineering crops to be Roundup-ready not being significantly unlike selectively breeding for sweet corn, stop and think before you imbibe. They may be passing you a cup of Googleberry Blast or Monsanto Mountain Punch. Fortunately, you will be able to recognize the cyanide-laced continuity argument at the bottom and dump it out. Your existence as a critical thinking member of technological civilization will depend on it. Peddling educational media and games is a lot like selling drugs to the parents of sick children: In both cases, the buyers are desperate. Those buying educational products often do so out of concern (or perhaps fear) for their child’s cognitive “health” and, thereby, their future as employable and successful adults. The hope is that some cognitive “treatment,” like a set of Baby Einstein DVDs or an iPad app, will ensure the “normal” mental development of their child, or perhaps provide them an advantage over other children. These practices are in some ways no different than anxiously shuttling infants and toddlers to pediatricians to see if they “are where they should be” or fretting over proper nutrition. However, the desperation and anxiety of parents serves as an incentive for those who develop and sell treatment options to overstate their benefits, if not outright deceive. Although regulations and institutions (i.e., the FDA) exist to help that ensure parents concerned about their son or daughter’s physiological development are not being swindled, those seeking to improve or ensure proper growth of their child’s cognitive abilities are on their own, and the market is replete with the educational equivalent of snake oil and laudanum.

Take the example of Baby Einstein. The developers of this DVD series promise that they are designed to “enrich your baby’s happiness” and “encourage [their] discovery of the world.” The implicit reference to Albert Einstein is meant to persuade parents that these DVDs provide a substantial educational benefit. Yet, there is good reason to be skeptical of Baby Einstein. The American Academy of Pediatrics, for instance, recommends against exposing children under two to television and movies to children as a precaution against the potential development harms. A 2007 study broke headlines when researchers found evidence that the daily watching of educational DVDs like Baby Einstein may slow communicative development in infants but had no significant effects on toddlers[1]. At the time, parents were already shelling out $200 million a year to Baby Einstein with the hope of stimulating their child’s brain. What they received, however, was likely no more than an overhyped electronic babysitter. Today, the new hot market for education technology is not DVDs but iPad and smartphone apps. Unsurprisingly, the cognitive benefits provided by them are just as uncertain. As Celilia Kang notes, “despite advertising claims, there are no major studies that show whether the technology is helpful or harmful.” Given this state of uncertainty, firms can overstate the benefits provided by their products and consumers have little to guide them in navigating the market. Parents are particularly easy marks. Much like how an individual receiving a drug or some other form of medical treatment is often in a poor epistemological position to evaluate its efficacy (they have little way of knowing how they would have turned out without treatment or with an alternative), parents generally cannot effectively appraise the cognitive boost given to their child by letting them watch a Baby Einstein DVD or play an ostensibly literacy-enhancing game on their iPad. They have no way of knowing if little Suzy would have learned her letters faster or slower with or without the educational technology, or if it were substituted with more time for play or being read to. They simply have no point of comparison. Lacking a time machine, they cannot repeat the experiment. Move over, some parents might be motivated to look for reasons to justify their spending on educational technologies or simply want to feel that they have agency in improving their child’s capacities. Therefore, they are likely to suffer from a confirmation bias. It is far too easy for parents to convince themselves that little David counted to ten because of their wise decision to purchase an app that bleats the numbers out of the tablet’s speakers when they jab their finger toward the correct box. Educational technologies have their own placebo effect. It just so happens to affect the minds of parents, not the child using the technology. Moreover, determining whether or not one’s child has been harmed is no easy matter. Changes in behavior could be either over or under estimated depending on to what extent parents suffers from an overly nostalgic memory of their own childhood or generational amnesia concerning real significant differences. Yet, it is not only parents and their children who may be harmed by wasting time and money on learning technologies that are either not substantively more effective or even cognitively damaging. School districts spend billions of taxpayer money on new digital curricula and tools with unproven efficacy. There are numerous products, from Carengie’s “Cognitive Tutor” to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s “Destination Reading,” that make extravagant claims about their efficacy but have been found not to significantly improve learning outcomes over traditional textbooks when reviewed by the Department of Education. Nevertheless, both are still for sale. Websites for these software packages claim that they are “based on over 20 years of research into how students think and learn” and “empirical research and practice that helps identify, prevent, and remediate reading difficulties.” Nowhere is it stated on the companies’ websites that third party research suggests that these expensive pieces of software may not actually improve outcomes. Even if some educational technologies prove to be somewhat more effective than a book or numbered blocks, they may still be undesirable for other reasons. Does an app cut into time that might otherwise be spent playing with parents or siblings? Children, on average, already spend seven hours each day in front of screens, which automatically translates into less time spent outdoors on non-electronic hobbies and interactions. The cultural presumption that improved educational outcomes always lie with the “latest and greatest” only exacerbates this situation. Do educational technologies in school districts come at the costs of jobs for teachers or cut into budgets for music and arts programs? The Los Angeles school district has cut thousands of teachers from their payroll in recent years but, as Carlo Rotella notes, is spending $500 million in bond money to purchase iPads. All the above concerns do not even broach the subject of how people raised on tablets might be changed in undesirable ways as a result. What sorts of expectations, beliefs and dispositions might their usage be more compatible? Given concerns about how technologies like the Internet influence how people think in general, concerned citizens should not let childhood be dominated by them without adequate debate and testing. Because of the potential for harm, uncertainty of benefit and the difficulty for consumers to be adequately informed concerning either, the US should develop an equivalent to the FDA for educational technologies. Many Americans trust the FDA to prevent recurrences of pharmaceutical mistakes like thalidomide, the morning sickness drug that led to dead and deformed babies. Why not entrust a similar institution to help ensure that future children are not cognitively stunted, as may have happened with Baby Einstein DVDs, or simply that parents and school districts do not waste money on the educational equivalent of 19th century hair tonics and “water cures?” The FDA, of course, is not perfect. Some aspects of human health are too complex to be parsed out through the kinds of experimental studies the FDA requires. Just think of the perpetual controversy over what percentage of people’s diet should come from fats, proteins and starches. Likewise, some promising treatments may never get pursued because the return on investment may not match the expenses incurred in getting FDA approval. The medicinal properties of some naturally occurring substances, for instance, have often not been substantively tested because, in that state, they cannot be patented. Finally, how to intervene in the development of children is ultimately a matter of values. Even pediatric science has been shaped by cultural assumptions about what an ideal adult looks like. For instance, mid-twentieth century pediatricians insisted, in contrast to thousands of years of human history, that sleeping alone promoted the healthiest outcomes for children. Today, it is easy to recognize that such science was shaped by Western myths of the self-reliant or rugged individual. The above problems would likely also affect any proposed agency for assessing educational technologies. What makes for “good” education depends on one's opinion concerning what kind of person education ought to produce. Is it more important that children can repeat the alphabet or count to ten at earlier and earlier ages or that they can approach the world with not only curiosity and wonder but also as a critical inquirer? Is the extension of the logic and aims of the formal education system to earlier and earlier ages via apps and other digital devices even desirable? Why not redirect some of the money going to proliferating iPad apps and robotic learning systems to ensuring all children have the option to attend something more like the "forest kindergartens" that have existed in Germany for decades? No scientific study that can answer such questions. Nevertheless, something like an Educational Technology Association would, in any case, represent one step toward a more ethically responsible and accountable educational technology industry. _______________________________________ [1] Like any controversial study, its findings are a topic of contention. Other scholars have suggested that the data could be made to show a positive, negative or neutral result, depending on statistical treatment. The authors of the original study have countered, arguing that the critics have not undermined the original conclusion that the educational benefits of these DVDs are dubious at best and may crowd-out more effective practices like parents reading to their children. During debates about some contemporary scientific controversy, such as GMO foods or the effects of climate change, someone almost invariably declares at some point to be on the “right side” of science. Opponents, accordingly, are implied to be either hopeless biased or under the spell of some form of pseudoscientific legerdemain. Confronted by just such an argument this week during a discussion over Elizabeth Warren’s vote against mandating the labeling of GMO ingredients, I was mostly struck by how profoundly unscientific and ignorant of the actual functioning of science and politics this rhetorical move is.

In order to avoid overstating my case, I should make clear that some knowledge claims are fairly straightforward and obvious cases of pseudoscience. Although philosophy of science has yet to develop unproblematic criteria for demarcating science from pseudoscience, the line between scientific approaches to inquiry and pseudoscientific ideology can be fuzzily drawn around such practices and dispositions as the willingness of practitioners to subject their claims to scrutiny or admit limitations to the theories they develop. Pyramid power and astrology are typical, though somewhat trivial, examples. The labels “scientific” and “pseudoscientific,” however, are best thought of as ideal types; the behaviors of most inquirers usually lie somewhere in between, and this is normally not a problem. Decades ago Ian Mitroff demonstrated the diversity of inquiry styles used practicing scientists. Science requires many types of researchers for its dynamism, from hardliner empiricists to armchair bound synthesizers and theoreticians – who may play more fast and loose with existing data. It is a social process that seems better characterized by the continual raising of new questions, evermore highlighting new uncertainties, complexities and limits to understanding, than the establishment of enduring and incontrovertible facts. Theories can almost always be refined or subjected to new challenges; data is invariably reinterpreted as new ideas and instruments are developed. At the same time, respected and successful scientists are generally not the exemplars of objectivity typically depicted in popular media, having pet theories and engaging in political wrangling with opponents. It is in light of this characterization of science that makes claims to being on the "right side of science" so troubling. The way the word “fact” is used attempts to transform the particular conclusion of scientific study from tentative conjecture based on incomplete data analyzed via inevitably imperfect techniques and technologies into something incontrovertible and unchallengeable. Even worse, it shuts down further inquiry, and there can be nothing more profoundly unscientific and epistemologically stale than eliminating the possibility for further questions or denying the inherent uncertainty and fallibilism of human claims to truth. Recognition of this, however, is frequently thrown out the window during the moments of controversy. Some opponents of GMO labeling contend that doing so automatically implies that genetically modified ingredients are harmful and lends credence to what they see as pseudoscientific fear mongering concerning their potential effects of human health. The person I was arguing with believed that the absence of what he considered to be a “strong” linkage between human or animal well-being and GMO food in the decades since their introduction rendered their safety a scientific “fact.” To begin, it is specious reasoning to assume that the absence of evidence is automatically evidence of absence. The presumption that the current state of research already adequately explored all the risks associated with a particular technology is dangerous and should not be made lightly. The historical record is full technologies, such as pesticides (DDT), medicines (Vioxx) or industrial chemicals (BPA), at one time thought to be safe and discovered to be dangerous only after put into widespread use. It is incredibly risky to project the universality of a particular present finding into the foreseeable future – when available methods, data and knowledge will likely be more sophisticated than in the present. Furthermore, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that it is only the potential health risks posed by the ingestion of GMO’s by individual consumers that we should be worried about. Any technology, like the manipulation of recombinant DNA, is part and parcel of a larger sociotechnical system. GMO foods are, for the foreseeable future, intertwined with particular ways of farming (industrial scale monoculture), certain economic arrangements (farmers utterly dependent on biotech firms like Monsanto) and specific ways of conceiving how human beings should relate to nature and food (as a pure commodity). Citizens may be legitimately concerned about any or all of the above facets of GMO food as a technology; many of these concerns, clearly, cannot be answered or done away with by conducting a scientific experiment. Regardless, the claim that science is on one’s side also fails to recognize how scientific studies are scrutinized in imbalanced ways and doubt manufactured when politically useful. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the controversy surrounding Seralini’s study purporting to find a link between cancer and the ingestion of GMO and RoundUp treated corn. As numerous ensuing commentaries point out, the connections drawn in the paper remain uncertain and the experimental design seemed to lack statistical power. Yet, many critics claimed the study was rubbish for its “nonstandard” methodological choices, even though they used many of the exact same methods as industry research claiming to demonstrate the safety of GMO food. My point is not to claim whether or not the effects observed by Seralini’s team is real or not but to note that scientists and various pundit are often incredibly inconsistent in their judgments of the flaws of a particular study or result. Imperfections tolerated in other studies seem to conveniently render controversial studies pseudoscientific when the results are incompatible with the critic’s other sociopolitical commitments, like the association of “progress” with the increasing application of biotechnology to food production, or powerful political interests. More broadly, the desire to be on the “right side of the facts” in controversial areas often takes on the form of a fetish. Such thinking seems founded on the hope that science can free humanity of the anxieties inherent in doing politics, which I think is best framed as the process of deciding how to organize civilization in the face of uncertainty, diversity and complexity. If a particular way of designing our collective lives can become enshrined in “fact,” than we no longer have to subject the choice to the messiness of democratic decision making or pursue the reconciliation of different interests and ideas about how human beings ought to live. Yet, if a particular scientific result is, at its best, something we can be only tentatively certain about and, at its worst, a falsehood only temporarily propped up by a constellation of inadequate theorizing, techniques and methodologies – or even cultural bias or outright fabrication, it would seem that science is generally not up to the task of freeing humanity from the need for politics. This point leads to one of the main problems with the way people tend to talk about “scientific controversies:” It is premised on a false dichotomy. Politics and good science are often taken to be polar opposites. It seems to presume that politics is the stuff of mere opinion and emotion and outside the realm of genuine inquiry. Such a dichotomy, to me, seems to do damage to our understandings of both of politics and science. The qualities celebrated in idealized versions of scientists – openness to new ways of thinking, self-reflective criticality and so on – seem to be qualities also befitting of political citizenship. At the same time, the assumption that science is the realm of absolute certainties and falsehoods – rather than the messy muddling through of various complexities, uncertainties and ignorances – leads to an interpretation of scientific findings that many practicing scientists themselves would not condone. The greatest challenges facing technological civilization are best met through inquiry, debate and the recognition of human ignorance, not blind faith in some naïve, fairy-tale understanding of science and fact. To presume that it is more "objective" or rational to have the opinions and arguments of a particular set of men and women wearing lab coats carry the most weight in deciding our collective futures is to simply smuggle in one set of interests and ideas about the good under the guise of “just siding with the facts.” Even worse, it fails to comprehend the partially social character of fact production and the inherent fallibility of human knowledge. An understanding of politics more befitting of those claiming a “scientific outlook” on reality would recognize that citizens and decision makers are inexorably locked in conflict-ridden processes of juggling facts, interests and ideas about the good life, all fraught with uncertainty. When more participants in a scientific controversy understand this, perhaps then we can have a more fruitful public dialogue about GMO foods or natural gas hydrofracking. Note: I have to give credit to Canadian musician Danny Michel for the inspiration for the title of this post: "If God's on Your Side Than Who's on Mine?" |

Details

AuthorTaylor C. Dotson is an associate professor at New Mexico Tech, a Science and Technology Studies scholar, and a research consultant with WHOA. He is the author of The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude is Destroying Democracy and Technically Together: Reconstructing Community in a Networked World. Here he posts his thoughts on issues mostly tangential to his current research. Archives

July 2023

Blog Posts

On Vaccine Mandates Escaping the Ecomodernist Binary No, Electing Joe Biden Didn't Save American Democracy When Does Someone Deserve to Be Called "Doctor"? If You Don't Want Outbreaks, Don't Have In-Person Classes How to Stop Worrying and Live with Conspiracy Theorists Democracy and the Nuclear Stalemate Reopening Colleges & Universities an Unwise, Needless Gamble Radiation Politics in a Pandemic What Critics of Planet of the Humans Get Wrong Why Scientific Literacy Won't End the Pandemic Community Life in the Playborhood Who Needs What Technology Analysis? The Pedagogy of Control Don't Shovel Shit The Decline of American Community Makes Parenting Miserable The Limits of Machine-Centered Medicine Why Arming Teachers is a Terrible Idea Why School Shootings are More Likely in the Networked Age Against Epistocracy Gun Control and Our Political Talk Semi-Autonomous Tech and Driver Impairment Community in the Age of Limited Liability Conservative Case for Progressive Politics Hyperloop Likely to Be Boondoggle Policing the Boundaries of Medicine Automating Medicine On the Myth of Net Neutrality On Americans' Acquiescence to Injustice Science, Politics, and Partisanship Moving Beyond Science and Pseudoscience in the Facilitated Communication Debate Privacy Threats and the Counterproductive Refuge of VPNs Andrew Potter's Macleans Shitstorm The (Inevitable?) Exportation of the American Way of Life The Irony of American Political Discourse: The Denial of Politics Why It Is Too Early for Sanders Supporters to Get Behind Hillary Clinton Science's Legitimacy Problem Forbes' Faith-Based Understanding of Science There is No Anti-Scientism Movement, and It’s a Shame Too American Pro Rugby Should Be Community-Owned Why Not Break the Internet? Working for Scraps Solar Freakin' Car Culture Mass Shooting Victims ARE on the Rise Are These Shoes Made for Running? Underpants Gnomes and the Technocratic Theory of Progress Don't Drink the GMO Kool-Aid! On Being Driven by Driverless Cars Why America Needs the Educational Equivalent of the FDA On Introversion, the Internet and the Importance of Small Talk I (Still) Don't Believe in Digital Dualism The Anatomy of a Trolley Accident The Allure of Technological Solipsism The Quixotic Dangers Inherent in Reading Too Much If Science Is on Your Side, Then Who's on Mine? The High Cost of Endless Novelty - Part II The High Cost of Endless Novelty Lock-up Your Wi-Fi Cards: Searching for the Good Life in a Technological Age The Symbolic Analyst Sweatshop in the Winner-Take-All Society On Digital Dualism: What Would Neil Postman Say? Redirecting the Technoscience Machine Battling my Cell Phone for the Good Life Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed