|

Back during the summer, Tristan Harris sparked a flurry of academic indignation when he suggested that we needed a new field called “Science & Technology Interaction” or STX, which would be dedicated to improving the alignment between technologies and social systems. Tweeters were quick to accuse him of “Columbizing,” claiming that such a field already existed in the form of Science & Technology Studies (STS) or similar such academic department. So ignorant, amirite?

I am far more sympathetic. If people like Harris (and earlier Cathy O’Neil) have been relatively unaware of fields like Science and Technology Studies, it is because much of the research within these disciplines is mostly illegible to non-academics, not all that useful to them, or both. I really don’t blame them for not knowing. I am even an STS scholar myself, and the table of contents of most issues of my field’s major journals don’t really inspire me to read further. And in fairness to Harris and contrary to Academic Twitter, the field of STX that he proposes does not already exist. The vast majority of STS articles and books dedicate single digit percentages of their words to actually imagining how technology could better match the aspirations of ordinary people and their communities. Next to no one details alternative technological designs or clear policy pathways toward a better future, at least not beyond a few pages at the end of a several-hundred-page manuscript. My target here is not just this particular critique of Harris, but the whole complex of academic opiners who cite Foucault and other social theory to make sure we know just how “problematic” non-academics’ “ignorant” efforts to improve technological society are. As essential as it is to try to improve upon the past in remaking our common world, most of these critiques don’t really provide any guidance for what steps we should be taking. And I think that if scholars are to be truly helpful to the rest of humanity they need to do more than tally and characterize problems in ever more nuanced ways. They need to offer more than the academic equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. In the case of Harris, we are told that underlying the more circumspect digital behavior that his organization advocates is a dangerous preoccupation with intentionality. The idea of being more intentional is tainted by the unsavory history of humanistic thought itself, which has been used for exclusionary purposes in the past. Left unsaid is exactly how exclusionary or even harmful it remains in the present. This kind of genealogical take down has become cliché. Consider how one Gizmodo blogger criticizes environmentalists’ use the word “natural” in their political activism. The reader is instructed that because early Europeans used the concept of nature to prop up racist ideas about Native Americans that the term is now inherently problematic and baseless. The reader is supposed to believe from this genealogical problematization that all human interactions with nature are equally natural or artificial, regardless of whether we choose to scale back industrial development or to erect giant machines to control the climate. Another common problematiziation is of the form “not everyone is privileged enough to…”, and it is often a fair objection. For instance, people differ in their individual ability to disconnect from seductive digital devices, whether due to work constraints or the affordability or ease of alternatives. But differences in circumstances similarly challenge people’s capacity to affordably see a therapist, retrofit their home to be more energy efficient, or bike to work (and one might add to that: read and understand Foucault). Yet most of these actions still accomplish some good in the world. Why is disconnection any more problematic than any other set of tactics that individuals use to imperfectly realize their values in an unequal and relatively undemocratic society? Should we just hold our breaths for the “total overhaul…full teardown and rebuild” of political economies that the far more astute critics demand? Equally trite are references to the “panopticon,” a metaphor that Foucault developed to describe how people’s awareness of being constantly surveilled leads them to police themselves. Being potentially visible at all times enables social control in insidious ways. A classic example is the Benthamite prison, where a solitary guard at the center cannot actually view all the prisoners simultaneously, but the potential for him to be viewing a prisoner at any given time is expected to reduce deviant behavior. This gets applied to nearly any area of life where people are visible to others, which means it is used to problematize nearly everything. Jill Grant uses it to take down the New Urbanist movement, which aspires (though fairly unsuccessfully) to build more walkable neighborhoods that are supportive of increased local community life. This movement is “problematic” because the densities it demands means that citizens are everywhere visible to their neighbors, opening up possibilities for the exercise of social control. Whether not any other way of housing human beings would not result in some form of residential panopticon is not exactly clear, except perhaps by designing neighborhoods so as to prohibit social community writ large. Further left unsaid in these critiques is exactly what a more desirable alternative would be. Or at least that alternative is left implicit and vague. For example, the pro-disconnection digital wellness movement is in need of enhanced wokeness, to better come to terms with “the political and ideological assumptions” that they take for granted and the “privileged” values they are attempting to enact in the world. But what does that actually mean? There’s a certain democratic thrust to the criticism, one that I can get behind. People disagree about what is “the good life” and how to get there, and any democratic society would be supportive of a multitude of them. Yet the criticism that the digital wellness movement seems to center around one vision of “being human,” one emphasizing mindfulness and a capacity to exercise circumspect individual choosing, seems hollow without the critics themselves showing us what should take its place. Whatever the flaws with digital wellness, it is not as self-stultifying as the defeatist brand of digital hedonism implicitly left in the wake of academic critiques that offer no concrete alternatives. Perhaps it is unfair to expect a full-blown alternative; yet few of these critiques offer even an incremental step in the right direction. Even worse, this line of criticism can problematize nearly everything, losing its rhetorical power as it is over-applied. Even academia itself is disciplining. STS has its own dominant paradigms, and critique is mobilized in order to mold young scholars into academics who cite the right people, quote the correct theories, and support the preferred values. My success depends on me being at least “docile enough” in conforming myself to the norms of the profession. I also exercise self-discipline in my efforts to be a better spouse and a better parent. I strive to be more intentional when I’m frustrated or angry, because I too often let my emotions shape my interactions with loved ones in ways that do not align with my broader aspirations. More intentionality in my life has been generally a good thing, so long as my expectations are not so unrealistic as to provoke more anxiety than the benefits are worth. But in a critical mode where self-discipline and intentionality automatically equate to self-subjugation, how exactly are people to exercise agency in improving their own lives? In any case, advocating devices that enable users to exercise greater intentionality over their digital practices is not a bad thing per se. Citizens pursue self-help, meditate, and engage in other individualistic wellness activities because the lives they live are constrained. Their agency is partly circumscribed by their jobs, family responsibilities, and incomes, not to mention the more systemic biases of culture and capitalism. Why is it wrong for groups like Harris’ center to advocate efforts that largely work within those constraints? Yet even that reading of the digital wellness movement seems uncharitable. Certainly Harris’ analysis lacks the sophistication of a technology scholar’s, but he has made it obvious that he recognizes that dominant business models and asymmetrical relations of power underlay the problem. To reduce his efforts to mere individualistic self-discipline is borderline dishonest, though he no doubt emphasizes the parts of the problem he understands best. Of course it will likely take more radical changes to realize the humane technology than Harris advocates, but it is not totally clear whether individualized efforts necessarily detract from people’s ability or the willingness demand more from tech firms and governments (i.e., are they like bottled water and other “inverted quarantines”?). At least that is a claim that should be demonstrated rather than presumed from the outset. At its worst, critical “problematizing” presents itself as its own kind of view from nowhere. For instance, because the idea of nature has been constructed in various biased throughout history, we are supposed to accept the view that all human activities are equally natural. And we are supposed to view that perspective as if it were itself an objective fact rather than yet another politically biased social construction. Various observers mobilize much the same critique about claims regarding the “realness” of digital interactions. Because presenting the category of “real life” as being apart from digital interactions is beset with Foulcauldian problematics, we are told that the proper response is to no longer attempt the qualitative distinctions that that category can help people make—whatever its limitations. It is probably no surprise that the same writer wanting to do away with the digital-real distinction is enthusiastic in their belief that the desires and pleasures of smartphones somehow inherently contain the “possibility…of disrupting the status quo.” Such critical takes give the impression that all technology scholarship can offer is a disempowering form of relativism, one that only thinly veils the author’s underlying political commitments. The critic’s partisanship is also frequently snuck in the backdoor by couching criticism in an abstract commitment to social justice. The fact that the digital wellness movement is dominated by tech bros and other affluent whites implies that it must be harmful to everyone else—a claim made by alluding to some unspecified amalgamation of oppressed persons (women, people of color, or non-cis citizens) who are insufficiently represented. It is assumed but not really demonstrated that people within the latter demographics would be unreceptive or even damaged by Harris’ approach. But given the lack of actual concrete harms laid out in these critiques, it is not clear whether the critics are actually advocating for those groups or that the social-theoretical existence of harms to them is just a convenient trope to make a mainly academic argument seem as if it actually mattered. People’s prospects for living well in the digital age would be improved if technology scholars more often eschewed the deconstructive critique from nowhere. I think they should act instead as “thoughtful partisans.” By that I mean that they would acknowledge that their work is guided by a specific set of interests and values, ones that are in the benefit of particular groups. It is not an impartial application of social theory to suggest that “realness” and “naturalness” are empty categories that should be dispensed with. And a more open and honest admission of partisanship would at least force writers to be upfront with readers regarding what the benefits would actually be to dispensing with those categories and who exactly would enjoy them—besides digital enthusiasts and ecomodernists. If academics were expected to use their analysis to the clear benefit of nameable and actually existing groups of citizens, scholars might do fewer trite Foucauldian analyses and more often do the far more difficult task of concretely outlining how a more desirable world might be possible. “The life of the critic easy,” notes Anton Ego in the Pixar film Ratatouille. Actually having skin in the game and putting oneself and one’s proposals out in the world where they can be scrutinized is far more challenging. Academics should be pushed to clearly articulate exactly how it is the novel concepts, arguments, observations, and claims they spend so much time developing actually benefit human beings who don’t have access to Elsevier or who don't receive seasonal catalogs from Oxford University Press. Without them doing so, I cannot imagine academia having much of a role in helping ordinary people live better in the digital age. Andrew Potter’s recent Maclean’s article claiming that Quebec is suffering from a pathological degree of social malaise has certainly raised eyebrows. Indeed, he has recently resigned from one of his posts at McGill University in response to public outcry—and no doubt the Quebec University’s administrations view of the matter. I won’t delve into the question regarding perceived damage to academic freedom that this resignation may or may not represent; rather, I take issue with the way in which Potter charts Quebec’s purported social decline—seeing it as reflective of a widespread failure to grasp the diverse character of social community.

On the one hand, some of the statistics Potter cites to support his case are alarming, especially those regarding the relatively small size of social networks and volunteering rates in Quebec. On the other hand, Quebec is noteworthy in terms of having one of the highest rates of happiness/social well-being in Canada. At a minimum, this apparent discrepancy is something that needs explained. One would, of course, scarcely imagine that a province suffering from widespread social malaise would be simultaneously happy. Potter, moreover, draws heavily on Robert Putnam’s concept of social capital, which posits that certain social and political activities help build the civic foundation for well-functioning democratic societies. Being familiar with Putnam's work—it has inspired my own research into the character of contemporary community life--I think that Andrew Potter has taken some liberties with it. Sure volunteering may be low, but Quebecers are known for being politically active, which is another contributor to and reflection of social capital. At the same time, Potter seems to conflate social capital with level of conformance to a non-Quebecer's idea of law and order. He argues that the colorful pants worn by police as a sign of corrosion of “social cohesion and trust in institutions.” While I am not an expert on Quebecois culture, it is hard not to see this as reflecting an English-Canadians cultural bias. Indeed, the impulse to denigrate protest and collective bargaining disproportionately afflicts Anglophones. For those less afflicted, the camo pants might evoke a feeling of solidarity. Left-wing Americans, for the sake of comparison, rarely decry the blocking of streets and highways during protests as the demise of social cohesion. That is not the only place where Potter could have been more sensitive to how cultural differences make social issues much more complex than one might initially think. He cites, for instance, the fact that far fewer Quebecers express the belief that “most people can be trusted.” As a social scientist Potter should be able to readily acknowledge that cultural differences can have a big impact on survey data. It is often claimed—on the basis of survey research--that Asian countries are much less happy than those in the West. However, once one recognizes the fact that readily labeling oneself as happy conflicts with Asian expectations for modesty, such interpretations of the survey data soon seem dubious. Given that Quebec’s rates of happiness and high marks in other dimensions of social capital, one wonders if individually low levels of trust simply reflects a cultural hesitancy to seem too trusting or gullible. Some of the confusion in Potter’s piece may be the result of not explicitly acknowledging different scales of analysis. Quebec is unique compared to other provinces in terms of its social policy (i.e., L'economie sociale): heavily subsidized daycare, generous support of cooperatives, high labor participation, etc. In many ways its citizens are more communitarian than people elsewhere, but more at the level of the province than locality or nation, more via official politics than through non-governmental volunteering. Maybe they don't quite have the ideal mixture by some accounts, but it seems hyperbolic to argue that the whole society is in a state of alienated malaise. In any case, both the controversy over Potter’s article and its analytical limitations are suggestive of the need for far better understandings of what community is. The term often evokes a fuzzy, warm feeling in some people, and worries about suppression of individuality in others. At the same time, few people seem aware of what exactly what they mean by the word: using it to describe racial groups (e.g., the black community), and online forum, and physical places—even though none of these things seem to be communal in even slightly the same way. Community is a multi-scalar, multi-dimensional, and highly diversified phenomenon. The sooner people recognize that, the sooner we can start to have more productive public conversation about what might be missing in contemporary forms of togetherness and how we might collectively realize more fulfilling alternatives. Adam Nossiter has recently published a fascinating look at the decline of small to medium French cities in the New York Times. I recommend not only reading the article but also perusing the comments section, for the latter gives some insight into the larger psycho-cultural barriers to realizing thicker communities.

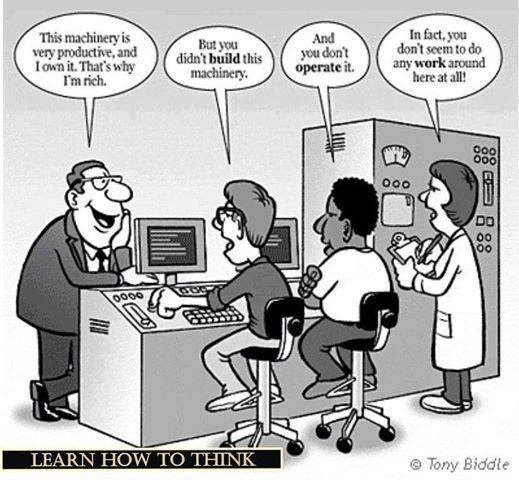

Nossiter's article is a lament over the gradual economic and social decline of Albi, a small city of around 50 thousand inhabitants not far from Toulouse. He is troubled by the extent to which the once vibrant downtown has become devoid of social and economic activity, apart from, that is, the periodic influx of tourists interested in its rustic charm as a medieval-era town. Nossiter's piece, however, is not a screed against tourists; rather, he notes that the large proportion of visitors can prevent one from noticing that the town itself now has few amenities to offer locals: It is a single bakery and no local butcher, grocery, or cafe. Residents obtain their needs from supermarkets and malls at the outskirts of town. One might be tempted to dismiss Nossiter's concerns as mere "nostalgia" in the face of "real progress." Indeed, many of those commenting on the article do just that, suggesting that young people want an exciting night life offered by nearby metropolises and that local shops are relics of the past that were destined to be destroyed by the ostensibly lower prices and greater efficiency of malls and big box stores. I think, however, that it is unwise to do so, if one wishes to think carefully and intelligently about the issue. Appeals to progress and inevitability are not so much statements of fact, indeed evidence to back them up is quite limited, but instead rhetorical moves meant to shut down debate; their aim, intentionally or not, is to naturalize a process that is actually sociopolitical. If France is at all like the United States, and I suspect it is, the erection of malls was nothing preordained but a product of innumerable policy decisions and failures of foresight. So contingent was the outcome on these external variables that it seems obtuse to try to claim that it was the result of simply providing consumers with what they wanted. Readers interested in the details can look forward to my soon to be released book Technically Together (MIT Press). For the purposes of this post I can only summarize a few of the ways in which downtown economic decay is not inevitable. The ability for a big-box store or mall to turn a profit is dependent on far more than just the owner's business acumen. Such stores are only attractive to the extent that governments spend public funds to make them easy to get to. Indeed, big box prices are low enough to attract Americans because of the invisible subsidy provided by citizens' tax dollars in building roads and highways. Many, if not most, malls and big box stores were built with public funds, either as the result of favorable tax deductions offered by municipalities or schemes like tax-increment financing. Lacking the political clout of the average corporate retailer, a local butcher is unlikely to receive the same deal. Other forms of subsidy are more indirect. Few shoppers factor in the additional costs of gasoline or car repairs when pursuing exurban discount shopping. Given AAA's estimate of the yearly cost of driving as in excess of ten thousand dollars per year, the full cost of a ten mile drive to the mall is significant, even if it is not salient to consumers. Indeed, they forget it by the time they arrive at the register. Moreover, what about the additional health care costs incurred by driving rather than walking or the psychic costs of living in areas no longer offering embodied community? Numerous studies have found that local community is one of the biggest contributors to a long life and spry old age. It seems unlikely to be mere coincidence that Americans have become increasing medicated against psychological disorders as their previously thick communities have fragmented into diffuse social networks. While these costs do not factor into the prices consumers enjoy via discount exurban shopping, citizens still pay them. Despite the fact that these sociopolitical drivers are fairly obvious if one takes the time to think about them, "just so" stories that try to explain the status quo as in line with the inexorable march of progress remain predominate. Psychologists have theorized that the power of such stories results from the intense psychological discomfort that many people would feel if faced with the possibility that the world as they know it is either unjust or was arrived at via less-than-fair means. Progress narratives are just one of the ways in which citizens psychically shore up an arbitrary and, in the view of many, undesirable status quo. Indeed, Americans, as well as Europeans and others to an increasing extent, seem to have an intense desire to justify the present by appealing to past abstract "market forces." Yale political economist Charles Lindblom argued that the tendency for citizens to reason their way into believing that what is good for economic elites is good for everyone was one of the main sources of business's relatively privileged position in society. In fact, many people go so far to talk as if the market were a dangerous but nonetheless productive animal that one must placate with favorable treatment and a long leash, apparently not realizing that acting in accordance to such logic makes the market system seem less like a beacon of freedom and more like a prison. One thing remains certain: As long as citizens think and act as if changes like the economic decline of downtown areas in small cities are merely the price of progress, it will be impossible to do anything but watch them decay. 8/4/2014 Why Are Scientists and Engineers Content to Work for Scraps when MBAs get a Seat at the Table?Read Now Report from TechnoScience as if People Mattered Why should it be that some of the most brilliant and highly educated people I know are forced to beg for jobs and justify their work to managers who, in all likelihood, might have spent a greater part of their business program drunk than studying? Sure there are probably some useful tasks that managers and supervisors perform, and some of them are no doubt perfectly wonderful people. Nevertheless, why should they sit at the top of the hierarchy of the contemporary firm while highly skilled technologists just do what they are told? Why should those who design and build new technologies or solve tenacious scientific problems receive a wage and not a large share in the wealth they help generate? Most importantly, why do so many highly skilled and otherwise intelligent people put up with this situation? There is nothing natural about MBAs and other professional managers running a firm like a captain of ship. As Harvard economist Stephen Marglin illustrated so well, the emergence of that hierarchical system had little to do with improvements in technological efficiency or competitive superiority but rather that it better served the interests of capitalist owners. What bosses “do” is maximize the benefits accruing to capitalists at the expense of workers. Bosses have historically and continue to do this by minimizing the scope each individual worker has in the firm and inserting themselves (i.e., management) as the obligatory intermediary for even the most elementary of procedures. This allows them to better surveil and discipline workers for the benefit of owners. Most highly skilled workers will probably recognize this if they reflect on all those seemingly pointless memos they are forced to read and write. Of course, some separation of labor (and writing of memos) is necessary for achieving efficient production processes, but the current power arrangement ensures that exactly how any process ends up being partitioned is ultimately decided by and for the benefit of managers and owners prior to any consideration of workers’ interests.

Even if one were not bothered by the life-sucking monotony of many jobs inflicted by a strict separation of labor, there is still little reason why the person in charge of coordinating everyone’s individual tasks ought to rule with almost unquestioned authority. This is a particularly odd arrangement for tech firms, given that scientists and engineers are highly skilled workers whose creative talents make up the core the company’s success. Moreover, these workers only receive a wage while others (e.g., venture capitalists, shareholders and select managers) get the lion’s share of the generated wealth: “Thanks for writing the code for that app that made us millions. Here, have a bonus and count yourself lucky to have a job.” Although frequently taken to be “just the way things are,” it need not be the case that the totality of the profits of innovation so disproportionately accrue to shareholders and select managers. Neither does one need look as far away as socialist nations in order to recognize this. Family-owned and “closely held” corporations in the United States already forgo lower rates of monetary profit in order to enjoy non-monetary benefits and yet remain competitive. For instance, Hobby Lobby, recently made infamous for other reasons, closes its stores on Sundays. They give up sales to competitors like Michaels because those running the firm believe that workers ought to have a guaranteed day in their schedule to spend time with friends and loved ones. Companies like Chick-Fil-A, Wegman’s and others pay their workers more livable wages and/or help fund their college educations, all practices unlikely to maximize shareholder value by any stretch of the imagination. At the same time, the hiring process for many managers does not lend much credence to the view that their skills alone make the difference between a successful or unsuccessful company. Michael Church, for instance, recently posted an account of the differences between applying to tech firm as a software engineer versus a manager. When interviewing as a software engineer, the applicant was subjected to a barrage of doubts about their skills and qualifications. The burden of proof was laid on the applicant to prove themselves worthy. In contrast, when applying for a management position, the same applicant was seen as “already part of the club” and was targeted with hardly any scrutiny at all. This is, of course, but one example. I encourage readers to share their own experiences in the comments section. Regardless, I suspect that if management is regularly treated like a club for those with the right status rather than the right competencies, their skills may not be so scarce or essential as to justify their higher wages, stake in company assets and discretion in decision-making. Young, highly skilled workers seem totally unaware of the power they could have in their working lives, if enough of them strove to seize it. I am not talking about unionization, though that could also be helpful. Instead, I am suggesting that scientists and engineers could own and manage their own firms, reversing (or simply leveling) the hierarchy with their current business-major overlords. Doing so would not be socialism but rather economic democracy: a worker cooperative. Workers outside the narrow echelon of managers and distant venture capitalists could have stake in the ownership of capital and thus power in the firm, making it much more likely that their interests are better reflected in decisions about operations and longer-term business plans. There is no immediately obvious reason why scientists and engineers could not start their own worker cooperatives. In fact, there are cases of workers less skilled and educated than the average software engineer helping govern and earning equity in their companies. The Evergreen cooperative in Cleveland, Ohio, for instance, consists of a laundry – mostly serving a nearby hospital, a greenhouse and a weatherization contractor. A small percentage of each worker’s salary goes into owning a stake in the cooperative, amounting to about $65,000 in wealth in roughly eight years. Workers elect their own representation to the firm’s board and thus get a say in its future direction and daily operation. Engineers, scientists and other technologists are intelligent enough to realize that the current “normal” business hierarchy offers them a raw deal. If laundry workers and gardeners can cooperatively run a profitable business while earning wealth, not merely a wage, certainly those with the highly specialized, creative skills always being extolled as being the engine of the “new knowledge economy” could as well. The main barrier is psychological. Engineers, scientists and other technologists have been encultured to think that things work out best if they remain mere problem solvers – more cynical observers might say overhyped technicians. Maybe they believe they will be one of the lucky ones to work somewhere with free pizza, breakout rooms and a six figure salary, or maybe they think they will eventually break into management themselves. Of course there is also the matter of the start-up capital that any tech firm needs to get off the ground. Yet, if enough technologists started their own cooperative firms, they could eventually pool resources to finance the beginnings of other cooperative ventures. All it would take is a few dozen enterprising people to show their peers that they do not have to work for scraps (even if there are sometimes large paychecks to go with that free pizza). Rather, they could take a seat at the table. Repost from TechnoScience as if People Mattered

There has been no shortage of both hype and skepticism surrounding a proposed innovation whose creators champion as potentially solving North America’s energy woes: Solar Roadways. While there are reasonable concerns about the technical and economic viability of incorporating solar panels into street and highways, almost completely ignored are the sociopolitical facets of the issue. Even if they end up being technically and financially feasible, the question of “Why should we want them?” remains unanswered. Too readily do commentators forget that at stake is not merely how Americans get their electricity but the very organization of everyday life and the character of their communities. Solar Roadways technology is the brainchild of an Idaho start-up. It involves sandwiching photovoltaics between a textured, tempered road surface and a concrete bedding that houses other necessary electronics, such as storage batteries and/or the circuitry needed to connect it to the electrical grid. Others have raised issue over the fairly rosy estimates of these panels’ likely cost and potential performance, including their driveability and longevity as well as whether or not factors like snowfall, low temperatures in northern states and road grime will drastically reduce their efficiency. Given that life cycle analyses of rooftop solar panels estimate energy payback periods of ten to twenty years, any reduction in efficiency makes PV systems much less feasible. Will the panels actually last long enough to offset the energy it takes to build, distribute and install them? The extensive history of expensive technological failures should alert citizens to the need to address such worries before this technology is embraced on a massive scale. However, these reasonable technical concerns should not distract one from looking into the potential sociocultural consequences of implementing solar roadways. One of the main observations of Science and Technology Studies scholarship is that technologies have political consequences: Their very existence and functioning renders some choices and sets of actions possible and others more difficult if not impossible. One of the most obvious examples is how the transportation infrastructures implemented since the 1940’s have rendered walkable, vibrant urban areas in the United States exceedingly difficult to realize. Residents of downtown Albany, for instance, are practically prohibited from being able to choose to have a pleasant waterfront area on the edge of the Hudson River because mid-twentieth century state legislators decided to put I-787 there (partly in order to facilitate their own commutes into the city). Contemporary advocates for an accessible and vibrant waterfront not only face opposition from today’s legislators but also the disincentives posed by the costs and difficulties of moving millions of tons of sunk concrete and disrupting the established transportation network. Solar Roadways, therefore, is not merely a promising green energy idea but also potentially a mechanism for further entrenching the current transportation system of roads and highways. It is politically consequential technology. Most citizens are already committed to the highway and automobile system for their transportation needs, in part also due to the intentional dismantling and neglect of public transit. Having to rely on the highway and road system for electricity would only make moving away from car culture and toward walkable cities more difficult. It is socially and politically challenging to alter infrastructure once it is entrenched. Dismantling a solarfied I-787 in Albany, for example, would not simply require disrupting transportation networks but energy systems as well. If states were to implement solar roadways, it would be effectively an act of legislation that helps ensure that automobile-oriented lifestyles remain dominant for decades to come. This further entrenchment of automobility may be exactly why the idea of solar roadways seems so enticing to some. Solar Roadways is an example of what is known in Science and Technology Studies as a “techno-fix.” It promises the solving of complex sociotechnical problems through a “miracle” innovation and, hence, without the need to make difficult social and political decisions (see here for an STS-inspired take). That is, solar roadways are so alluring because they seem to provide an easy solution to the problems of climate change and growing energy scarcity. No need to implement carbon taxes, drive less or better regulate industry and the exploitation non-renewable resources, the technology will fix everything! To be fair, techno-fixes are not always bad. The point is only that one should be cautiously critical of them in order to not risk falling victim to wide-eyed techno-idealism. Some readers, of course, might still be skeptical of my interpretation of solar roadways as techno-fix perhaps aimed more at saving car culture than creating a more sustainable technological civilization. However, one simply need to ask “Why roadways rather than rooftops?” It does not take much expertise in renewable energy technologies to recognize that solar panels on rooftops make much more sense than on streets, highways and parking lots: They last longer because they are not subject to having cars and trucks drive on them; they can be angled to maximize the incidence of the sun’s rays; and there is likely just as much unused roof space as asphalt. Given all the additional barriers they face, it seems hard to deny that some of appeal of solar roadways is not technical but cultural: They promise the stabilization and entrenchment of a valued but likely unsustainable way of life. Nevertheless, I do not want to simply shoot down solar roadway technology but ask “How could it be used to support ways of life other than car culture?” Critically analyzing a technology from a Science and Technology Studies perspective can often lead to recommendations for its reconstruction, not simply its abandonment. I would suggest reinterpreting this proposed innovation as solar walkways rather than roadways, given that their longevity is more certain if subjected to footsteps instead of multi-ton vehicles. Moreover, as urban studies scholars have documented for decades, most urban and suburban spaces in North America suffer from a lack of quality public space. City plazas and town squares might seem more “rational” to municipal planners if their walking surfaces were made up of PV panels. Better yet, consider incorporating piezoelectrics at the same time and generate additional electricity from the pedestrians walking on it. Feed this energy into a collectively owned community energy system and one has the makings of a technology that, along with a number of other sociotechnical and political changes, could help make more vibrant, public urban spaces easier to realize. Citizens, certainly, could decide that solar walkways are no more feasible or attractive than solar roadways, and should investigate potential uses that go far beyond what I have suggested. Regardless, part of the point of Science and Technology Studies is to creatively re-imagine how technologies and social structures could mutually reinforce each other in order to support alternative or more desirable ways of life. Despite all the Silicon Valley rhetoric around “disruption,” new innovations tend be framed and implemented in ways that favor the status quo and, in turn, those who benefit from it. The supposed “disruption” posed by solar roadway technology is little different. Members of technological civilization would be better off if they not only asked of new innovations “Is it feasible?” but also “Does it support a sustainable and desirable way of life?” Solar freakin’ roadways might be viable, but citizens should reconsider if they really want the solar freakin’ car culture that comes with it. Peddling educational media and games is a lot like selling drugs to the parents of sick children: In both cases, the buyers are desperate. Those buying educational products often do so out of concern (or perhaps fear) for their child’s cognitive “health” and, thereby, their future as employable and successful adults. The hope is that some cognitive “treatment,” like a set of Baby Einstein DVDs or an iPad app, will ensure the “normal” mental development of their child, or perhaps provide them an advantage over other children. These practices are in some ways no different than anxiously shuttling infants and toddlers to pediatricians to see if they “are where they should be” or fretting over proper nutrition. However, the desperation and anxiety of parents serves as an incentive for those who develop and sell treatment options to overstate their benefits, if not outright deceive. Although regulations and institutions (i.e., the FDA) exist to help that ensure parents concerned about their son or daughter’s physiological development are not being swindled, those seeking to improve or ensure proper growth of their child’s cognitive abilities are on their own, and the market is replete with the educational equivalent of snake oil and laudanum.

Take the example of Baby Einstein. The developers of this DVD series promise that they are designed to “enrich your baby’s happiness” and “encourage [their] discovery of the world.” The implicit reference to Albert Einstein is meant to persuade parents that these DVDs provide a substantial educational benefit. Yet, there is good reason to be skeptical of Baby Einstein. The American Academy of Pediatrics, for instance, recommends against exposing children under two to television and movies to children as a precaution against the potential development harms. A 2007 study broke headlines when researchers found evidence that the daily watching of educational DVDs like Baby Einstein may slow communicative development in infants but had no significant effects on toddlers[1]. At the time, parents were already shelling out $200 million a year to Baby Einstein with the hope of stimulating their child’s brain. What they received, however, was likely no more than an overhyped electronic babysitter. Today, the new hot market for education technology is not DVDs but iPad and smartphone apps. Unsurprisingly, the cognitive benefits provided by them are just as uncertain. As Celilia Kang notes, “despite advertising claims, there are no major studies that show whether the technology is helpful or harmful.” Given this state of uncertainty, firms can overstate the benefits provided by their products and consumers have little to guide them in navigating the market. Parents are particularly easy marks. Much like how an individual receiving a drug or some other form of medical treatment is often in a poor epistemological position to evaluate its efficacy (they have little way of knowing how they would have turned out without treatment or with an alternative), parents generally cannot effectively appraise the cognitive boost given to their child by letting them watch a Baby Einstein DVD or play an ostensibly literacy-enhancing game on their iPad. They have no way of knowing if little Suzy would have learned her letters faster or slower with or without the educational technology, or if it were substituted with more time for play or being read to. They simply have no point of comparison. Lacking a time machine, they cannot repeat the experiment. Move over, some parents might be motivated to look for reasons to justify their spending on educational technologies or simply want to feel that they have agency in improving their child’s capacities. Therefore, they are likely to suffer from a confirmation bias. It is far too easy for parents to convince themselves that little David counted to ten because of their wise decision to purchase an app that bleats the numbers out of the tablet’s speakers when they jab their finger toward the correct box. Educational technologies have their own placebo effect. It just so happens to affect the minds of parents, not the child using the technology. Moreover, determining whether or not one’s child has been harmed is no easy matter. Changes in behavior could be either over or under estimated depending on to what extent parents suffers from an overly nostalgic memory of their own childhood or generational amnesia concerning real significant differences. Yet, it is not only parents and their children who may be harmed by wasting time and money on learning technologies that are either not substantively more effective or even cognitively damaging. School districts spend billions of taxpayer money on new digital curricula and tools with unproven efficacy. There are numerous products, from Carengie’s “Cognitive Tutor” to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s “Destination Reading,” that make extravagant claims about their efficacy but have been found not to significantly improve learning outcomes over traditional textbooks when reviewed by the Department of Education. Nevertheless, both are still for sale. Websites for these software packages claim that they are “based on over 20 years of research into how students think and learn” and “empirical research and practice that helps identify, prevent, and remediate reading difficulties.” Nowhere is it stated on the companies’ websites that third party research suggests that these expensive pieces of software may not actually improve outcomes. Even if some educational technologies prove to be somewhat more effective than a book or numbered blocks, they may still be undesirable for other reasons. Does an app cut into time that might otherwise be spent playing with parents or siblings? Children, on average, already spend seven hours each day in front of screens, which automatically translates into less time spent outdoors on non-electronic hobbies and interactions. The cultural presumption that improved educational outcomes always lie with the “latest and greatest” only exacerbates this situation. Do educational technologies in school districts come at the costs of jobs for teachers or cut into budgets for music and arts programs? The Los Angeles school district has cut thousands of teachers from their payroll in recent years but, as Carlo Rotella notes, is spending $500 million in bond money to purchase iPads. All the above concerns do not even broach the subject of how people raised on tablets might be changed in undesirable ways as a result. What sorts of expectations, beliefs and dispositions might their usage be more compatible? Given concerns about how technologies like the Internet influence how people think in general, concerned citizens should not let childhood be dominated by them without adequate debate and testing. Because of the potential for harm, uncertainty of benefit and the difficulty for consumers to be adequately informed concerning either, the US should develop an equivalent to the FDA for educational technologies. Many Americans trust the FDA to prevent recurrences of pharmaceutical mistakes like thalidomide, the morning sickness drug that led to dead and deformed babies. Why not entrust a similar institution to help ensure that future children are not cognitively stunted, as may have happened with Baby Einstein DVDs, or simply that parents and school districts do not waste money on the educational equivalent of 19th century hair tonics and “water cures?” The FDA, of course, is not perfect. Some aspects of human health are too complex to be parsed out through the kinds of experimental studies the FDA requires. Just think of the perpetual controversy over what percentage of people’s diet should come from fats, proteins and starches. Likewise, some promising treatments may never get pursued because the return on investment may not match the expenses incurred in getting FDA approval. The medicinal properties of some naturally occurring substances, for instance, have often not been substantively tested because, in that state, they cannot be patented. Finally, how to intervene in the development of children is ultimately a matter of values. Even pediatric science has been shaped by cultural assumptions about what an ideal adult looks like. For instance, mid-twentieth century pediatricians insisted, in contrast to thousands of years of human history, that sleeping alone promoted the healthiest outcomes for children. Today, it is easy to recognize that such science was shaped by Western myths of the self-reliant or rugged individual. The above problems would likely also affect any proposed agency for assessing educational technologies. What makes for “good” education depends on one's opinion concerning what kind of person education ought to produce. Is it more important that children can repeat the alphabet or count to ten at earlier and earlier ages or that they can approach the world with not only curiosity and wonder but also as a critical inquirer? Is the extension of the logic and aims of the formal education system to earlier and earlier ages via apps and other digital devices even desirable? Why not redirect some of the money going to proliferating iPad apps and robotic learning systems to ensuring all children have the option to attend something more like the "forest kindergartens" that have existed in Germany for decades? No scientific study that can answer such questions. Nevertheless, something like an Educational Technology Association would, in any case, represent one step toward a more ethically responsible and accountable educational technology industry. _______________________________________ [1] Like any controversial study, its findings are a topic of contention. Other scholars have suggested that the data could be made to show a positive, negative or neutral result, depending on statistical treatment. The authors of the original study have countered, arguing that the critics have not undermined the original conclusion that the educational benefits of these DVDs are dubious at best and may crowd-out more effective practices like parents reading to their children. A recent interview in The Atlantic with a man who believes himself to be in a relationship with two “Real Dolls” illustrates what I think is one of the most significant challenges raised by certain technological innovations as well as the importance of holding on to the idea of authenticity in the face of post-modern skepticism. Much like Evan Selinger’s prescient warnings about the cult of efficiency and the tendency for people to recast traditional forms of civility as onerous inconveniences in response to affordances of new communication technologies, I want to argue that the burdens of human relationships, of which “virtual other” technologies promise to free their users, are actually what makes them valuable and authentic.[1] The Atlantic article consists of an interview with “Davecat,” a man who owns and has “sex” with two Real Dolls – highly realistic-looking but inanimate silicone mannequins. Davecat argues that his choice to pursue relationships with “synthetic humans” is a legitimate one. He justifies his lifestyle preferences by contending that “a synthetic will never lie to you, cheat on you, criticize you, or be otherwise disagreeable.” The two objects of his affection are not mere inanimate objects to Davecat but people with backstories, albeit ones of his own invention. Davecat presents himself as someone fully content with his life: “At this stage in the game, I'd have to say that I'm about 99 percent fulfilled. Every time I return home, there are two gorgeous synthetic women waiting for me, who both act as creative muses, photo models, and romantic partners. They make my flat less empty, and I never have to worry about them becoming disagreeable.” In some ways, Davecat’s relationships with his dolls are incontrovertibly real. His emotions strike him as real, and he acts as if his partners were organic humans. Yet, in other ways, they are inauthentic simulations. His partners have no subjectivities of their own, only what springs from Davecat’s own imagination. They “do” only what he commands them to do. They are “real” people only insofar as they are real to Davecat’s mind and his alone. In other words, Davecat’s romantic life amounts to a technologically afforded form of solipsism. Many fans of post-modernist theory would likely scoff at the mere word, authenticity being as detestable as the word “natural” as well as part and parcel of philosophically and politically suspect dualisms. Indeed, authenticity is not something wholly found out in the world but a category developed by people. Yet, in the end, the result of post-modern deconstruction is not to get to truth but to support an alternative social construction, one ostensibly more desirable to the person doing the deconstructing.  As the philosopher Charles Taylor[2] has outlined, much of contemporary culture and post-modernist thought itself is dominated by an ideal of authenticity no less problematic. That ethic involves the moral imperative to “be true to oneself” and that self-realization and identity are both inwardly developed. Deviant and narcissistic forms of this ethic emerge when the dialogical character of human being is forgotten. It is presumed that the self can somehow be developed independently of others, as if humans were not socially shaped beings but wholly independent, self-authoring minds. Post-modernist thinkers slide toward this deviant ideal of authenticity, according to Taylor, in their heroization of the solitary artist and their tendency to equate being with the aesthetic. One need only look to post-modernist architecture to see the practical conclusions of such an ideal: buildings constructed without concern for the significance of the surrounding neighborhood into which it will be placed or as part of continuing dialogue about architectural significance. The architect seeks only full license to erect a monument to their own ego. Non-narcissistic authenticity, as Taylor seems to suggest, is realizable only in self-realization vis-à-vis the intersubjective engagement with others. As such, Davecat’s sexual preferences for “synthetic humans” do not amount to a sexual orientation as legitimate as those of homosexuals or other queer peoples who have strived for recognition in recent decades. To equate the two is to do the latter a disservice. Both may face forms of social ridicule for their practices but that is where the similarities end. Members of homosexual relationships have their own subjectivities, which each must negotiate and respect to some extent if the relationship itself is to flourish. All just and loving relationships involve give-and-take, compromise and understanding and sometimes, hardship and disappointment. Davecat’s relationship with his dolls is narcissistic because there is no possibility for such a dialogue and the coming to terms with his partners’ subjectivities. In the end, only his own self-referential preferences matter. Relationships with real dolls are better thought of as morally commodified versions of authentic relationships. Borgmann[3] defines a practice as morally commodified “when it is detached from its context of engagement with a time, a place, and a community” (p. 152). Although Davecat engages in a community of “iDollators,” his interactions with his dolls has is detached from the context of engagement typical for human relationships. Much like how mealtimes are morally commodified when replaced by an individualize “refueling” at a fast-food joint or with a microwave dinner, Davecat’s dolls serve only to “refuel” his own psychic and sexual needs at the time, place and manner of his choosing. He does not engage with his dolls but consumes them. At the same time, “virtual other” technologies are highly alluring. They can serve as “techno-fixes” to those lacking the skills or dispositions needed for stable relationships or those without supportive social networks (e.g., the elderly). Would not labeling them as inauthentic demean the experiences of those who need them? Yet, as currently envisioned, Real Dolls and non-sexually-oriented virtual other technologies do not aim to render their users more capable of human relationships or help them become re-established in a community of others but provide an anodyne for their loneliness, an escape from or surrogate for the human social community of which they find themselves on the outside. Without a feasible pathway toward non-solipsistic relationships, the embrace of virtual other technologies for the lonely and relationally inept amounts to giving up on them, which suggests that it is better for them to remain in a state of arrested development. Another danger is well articulated by the psychologist Sherry Turkle.[4] Far from being mere therapeutic aids, such devices are used to hide from the risks of social intimacy and risk altering collective expectations for human relationships. That is, she worries that the standards of efficiency and egoistic control afforded by robots comes to be the standard by which all relationships come to be judged. Indeed, her detailed clinical and observational data belies just such a claim. Rather than being able to simply wave off the normalizing and advancement of Real Dolls and similar technologies as a “personal choice,” Turkle’s work forces one to recognize that cascading cultural consequences result from the technologies that societies permit to flourish. The amount of dollars spent on technological surrogates for social relationships is staggering. The various sex dolls on the market and the robots being bought for nursing homes cost several thousand dollars apiece. If that money could be incrementally redirected, through tax and subsidy, toward building the kinds of material, economic and political infrastructures that have supported community at other places and times, there would be much less need for such techno-fixes. Much like what Michele Willson[5] argues about digital technologies in general, they are technologies “sought to solve the problem of compartmentalization and disconnection that is partly a consequence of extended and abstracted relations brought about by the use of technology” (p. 80). The market for Real Dolls, therapy robots for the elderly and other forms of allaying loneliness (e.g., television) is so strong because alternatives have been undermined and dismantled. The demise of rich opportunities for public associational life and community-centering cafes and pubs has been well documented, hollowed out in part by suburban living and the rise of television. [6] The most important response to Real Dolls and other virtual other technologies is to actually pursue a public debate about what citizens’ would like their communities to look like, how they should function and which technologies are supportive of those ends. It would be the height of naiveté to presume the market or some invisible hand of technological innovation simply provides what people want. As research in Science and Technology Studies make clear, technological innovation is not autonomous, but neither has it been intelligently steered. The pursuit of mostly fictitious and narcissistic relationships with dolls is of questionable desirability, individually and collectively; a civilization that deserves the label of civilized would not sit idly by as such technologies and its champions alter the cultural landscape by which it understands human relationships. ____________________________________ [1] I made many of these same points in an article I published last year in AI & Society, which will hopefully exit “OnlineFirst” limbo and appear in an issue at some point. [2] Taylor, Charles. (1991). The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [3] Borgmann, Albert. (2006). Real American Ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [4] Turkle, Sherry. (2012). Alone Together. New York: Basic Books. [5] Willson, Michele. (2006). Technically Together. New York: Peter Lang. [6] See: Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone. New York: Simon & Schuster and Oldenburg, Ray. (1999). The Great Good Place. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. During debates about some contemporary scientific controversy, such as GMO foods or the effects of climate change, someone almost invariably declares at some point to be on the “right side” of science. Opponents, accordingly, are implied to be either hopeless biased or under the spell of some form of pseudoscientific legerdemain. Confronted by just such an argument this week during a discussion over Elizabeth Warren’s vote against mandating the labeling of GMO ingredients, I was mostly struck by how profoundly unscientific and ignorant of the actual functioning of science and politics this rhetorical move is.

In order to avoid overstating my case, I should make clear that some knowledge claims are fairly straightforward and obvious cases of pseudoscience. Although philosophy of science has yet to develop unproblematic criteria for demarcating science from pseudoscience, the line between scientific approaches to inquiry and pseudoscientific ideology can be fuzzily drawn around such practices and dispositions as the willingness of practitioners to subject their claims to scrutiny or admit limitations to the theories they develop. Pyramid power and astrology are typical, though somewhat trivial, examples. The labels “scientific” and “pseudoscientific,” however, are best thought of as ideal types; the behaviors of most inquirers usually lie somewhere in between, and this is normally not a problem. Decades ago Ian Mitroff demonstrated the diversity of inquiry styles used practicing scientists. Science requires many types of researchers for its dynamism, from hardliner empiricists to armchair bound synthesizers and theoreticians – who may play more fast and loose with existing data. It is a social process that seems better characterized by the continual raising of new questions, evermore highlighting new uncertainties, complexities and limits to understanding, than the establishment of enduring and incontrovertible facts. Theories can almost always be refined or subjected to new challenges; data is invariably reinterpreted as new ideas and instruments are developed. At the same time, respected and successful scientists are generally not the exemplars of objectivity typically depicted in popular media, having pet theories and engaging in political wrangling with opponents. It is in light of this characterization of science that makes claims to being on the "right side of science" so troubling. The way the word “fact” is used attempts to transform the particular conclusion of scientific study from tentative conjecture based on incomplete data analyzed via inevitably imperfect techniques and technologies into something incontrovertible and unchallengeable. Even worse, it shuts down further inquiry, and there can be nothing more profoundly unscientific and epistemologically stale than eliminating the possibility for further questions or denying the inherent uncertainty and fallibilism of human claims to truth. Recognition of this, however, is frequently thrown out the window during the moments of controversy. Some opponents of GMO labeling contend that doing so automatically implies that genetically modified ingredients are harmful and lends credence to what they see as pseudoscientific fear mongering concerning their potential effects of human health. The person I was arguing with believed that the absence of what he considered to be a “strong” linkage between human or animal well-being and GMO food in the decades since their introduction rendered their safety a scientific “fact.” To begin, it is specious reasoning to assume that the absence of evidence is automatically evidence of absence. The presumption that the current state of research already adequately explored all the risks associated with a particular technology is dangerous and should not be made lightly. The historical record is full technologies, such as pesticides (DDT), medicines (Vioxx) or industrial chemicals (BPA), at one time thought to be safe and discovered to be dangerous only after put into widespread use. It is incredibly risky to project the universality of a particular present finding into the foreseeable future – when available methods, data and knowledge will likely be more sophisticated than in the present. Furthermore, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that it is only the potential health risks posed by the ingestion of GMO’s by individual consumers that we should be worried about. Any technology, like the manipulation of recombinant DNA, is part and parcel of a larger sociotechnical system. GMO foods are, for the foreseeable future, intertwined with particular ways of farming (industrial scale monoculture), certain economic arrangements (farmers utterly dependent on biotech firms like Monsanto) and specific ways of conceiving how human beings should relate to nature and food (as a pure commodity). Citizens may be legitimately concerned about any or all of the above facets of GMO food as a technology; many of these concerns, clearly, cannot be answered or done away with by conducting a scientific experiment. Regardless, the claim that science is on one’s side also fails to recognize how scientific studies are scrutinized in imbalanced ways and doubt manufactured when politically useful. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the controversy surrounding Seralini’s study purporting to find a link between cancer and the ingestion of GMO and RoundUp treated corn. As numerous ensuing commentaries point out, the connections drawn in the paper remain uncertain and the experimental design seemed to lack statistical power. Yet, many critics claimed the study was rubbish for its “nonstandard” methodological choices, even though they used many of the exact same methods as industry research claiming to demonstrate the safety of GMO food. My point is not to claim whether or not the effects observed by Seralini’s team is real or not but to note that scientists and various pundit are often incredibly inconsistent in their judgments of the flaws of a particular study or result. Imperfections tolerated in other studies seem to conveniently render controversial studies pseudoscientific when the results are incompatible with the critic’s other sociopolitical commitments, like the association of “progress” with the increasing application of biotechnology to food production, or powerful political interests. More broadly, the desire to be on the “right side of the facts” in controversial areas often takes on the form of a fetish. Such thinking seems founded on the hope that science can free humanity of the anxieties inherent in doing politics, which I think is best framed as the process of deciding how to organize civilization in the face of uncertainty, diversity and complexity. If a particular way of designing our collective lives can become enshrined in “fact,” than we no longer have to subject the choice to the messiness of democratic decision making or pursue the reconciliation of different interests and ideas about how human beings ought to live. Yet, if a particular scientific result is, at its best, something we can be only tentatively certain about and, at its worst, a falsehood only temporarily propped up by a constellation of inadequate theorizing, techniques and methodologies – or even cultural bias or outright fabrication, it would seem that science is generally not up to the task of freeing humanity from the need for politics. This point leads to one of the main problems with the way people tend to talk about “scientific controversies:” It is premised on a false dichotomy. Politics and good science are often taken to be polar opposites. It seems to presume that politics is the stuff of mere opinion and emotion and outside the realm of genuine inquiry. Such a dichotomy, to me, seems to do damage to our understandings of both of politics and science. The qualities celebrated in idealized versions of scientists – openness to new ways of thinking, self-reflective criticality and so on – seem to be qualities also befitting of political citizenship. At the same time, the assumption that science is the realm of absolute certainties and falsehoods – rather than the messy muddling through of various complexities, uncertainties and ignorances – leads to an interpretation of scientific findings that many practicing scientists themselves would not condone. The greatest challenges facing technological civilization are best met through inquiry, debate and the recognition of human ignorance, not blind faith in some naïve, fairy-tale understanding of science and fact. To presume that it is more "objective" or rational to have the opinions and arguments of a particular set of men and women wearing lab coats carry the most weight in deciding our collective futures is to simply smuggle in one set of interests and ideas about the good under the guise of “just siding with the facts.” Even worse, it fails to comprehend the partially social character of fact production and the inherent fallibility of human knowledge. An understanding of politics more befitting of those claiming a “scientific outlook” on reality would recognize that citizens and decision makers are inexorably locked in conflict-ridden processes of juggling facts, interests and ideas about the good life, all fraught with uncertainty. When more participants in a scientific controversy understand this, perhaps then we can have a more fruitful public dialogue about GMO foods or natural gas hydrofracking. Note: I have to give credit to Canadian musician Danny Michel for the inspiration for the title of this post: "If God's on Your Side Than Who's on Mine?" In my last post, I considered some of the consequences of instantly available and seemingly endless quantities of Internet-driven novelty for the good life, particularly in the areas of story and joke telling as well as how we converse and think about our lives. This week, I want to focus more on the challenges to willpower exacerbated by Internet devices. Particularly, I am concerned with how today’s generation of parents, facing their own particular limitations of will, may be encouraging their children to have a relationship with screens that might be best described as fetishistic. My interest is not merely with the consequences for learning, although psychological research does connect media-multitasking with certain cognitive and memory deficits. Rather, I am worried about the ways in which some technologies too readily seduce their users into distracted and fragmented ways of living rather than enhancing their capacity to pursue the good life.

A recent piece in Slate overviews much of recent research concerning the negative educational consequences of media multitasking. Unsurprisingly, students who allowed their focus to be interrupted by a text or some other digital task, whether in lecture or studying, perform significantly worse. The article, more importantly, notes the special challenge that digital devices pose to self-discipline, suggesting that such devices are the contemporary equivalent to the “marshmallow test.” The Stanford marshmallow experiment was a series of longitudinal studies that found children's capacity to delay gratification to be correlated with their later educational successes and body-mass index, among other factors. In the case of these experiments, children were rated according their ability to forgo eating a marshmallow, pretzel or cookie sitting in front of them in order to obtain two later on. Follow-up studies have shown that this capacity for self-discipline is likely as much environmental as innate; children in “unreliable environments,” where experimenters would make unrelated promises and then break them, exhibited a far lower ability to wait before succumbing to temptation. The reader may reasonably wonder at this point, what do experiments tempting children with marshmallows have to do with iPhones? The psychologist Roy Baumeister argues that the capacity to exert willpower behaves like a limited resource, generally declining after repeated challenges. By recognizing this aspect of human self-discipline, the specific challenge of device-driven novelty is clearer. Today, more and more time and effort must be expended in exerting self-control over various digital temptations, more quickly depleting the average person's reserves of willpower. Of course, there are innumerable non-digital temptations and distractions that people are faced with everyday, but they are of a decidedly different character. I can just as easily shirk by reading a newspaper. At some point, however, I run out of articles. The particular allure of a blinking email notice or instant message that always seems to demand one’s immediate attention cannot be discounted either. Although it is not yet clear what the broader effects of pervasive digital challenges to willpower and self-discipline will be, other emerging practices will likely only exacerbate the consequences. The portability of contemporary digital devices, for instance, has enabled the move from “TV as babysitter” to media tablet as pacifier. A significant portion of surveyed parents admit to using a smart phone or iPad in order to distract their children at dinners and during car rides. Parents, of course, should not bear all of the blame for doing so; they face their own limits to willpower due to their often hectic and stressful working lives. Nevertheless, this practice is worrisome not only because it fails to teach children ways of occupying themselves that do not involve staring into a screen but also since the device is being used foremost as a potentially pathological means of pacification. I have observed a number of parents stuffing a smart phone in their child’s face to prevent or stop a tantrum. While doing so is usually effective, I worry about the longer term consequences. Using a media device as the sole curative to their children’s’ emotional distress and anxiety threatens to create a potentially fetishistic relationship between the child and the technology. That is, the tablet or smart phone becomes like a security blanket – an object that allays anxiety; it is a security blanket, however, that the child does not have give up as he or she gets older. This sort of fetishism has already become fodder for cultural commentary. In the television show “The Office,” the temporary worker named Ryan generally serves as a caricature of the millennial generation. In one episode, he leaves his co-workers in the lurch during a trivia contest after being told he cannot both have his phone and participate. Forced to decide between helping his colleagues win the contest and being able to touch his phone, Ryan chooses the latter. This is, of course, a fictional example but, I think, not too unrealistic a depiction of the likely emotional response. I am unsure if many of the college students I teach would not feel a similar sort of distress if (forcibly) separated from their phones. This sort of affect-rich, borderline fetishistic, connection with a device can only make more difficult the attempt to live in any way other than by the device’s own logic or script. How easily can users resist the distractions emerging from a technological device that comes to double as their equivalent to a child’s security blanket? Yet, many of my colleagues would view my concerns about people’s capacities for self-discipline with suspicion. For those having read (perhaps too much) Michel Foucault, notions of self-discipline tend to be understood as a means for the state or some other powerful entity to turn humans into docile subjects. In seminar discussions, places like gyms are often viewed as sites of self-repression first and promoting of physical well-being second. There is, to be fair, a bit of truth to this. Much of the design of early compulsory schooling, for instance, was aimed at producing diligent office and factory workers who followed the rules, were able to sit still for hours and could tolerate both rigid hierarchies and ungodly amounts of tedium. Yet, just because the instilling of self-discipline can be convenient for those who desire a pacified populace does not mean it is everywhere and always problematic. The ability to work for longer than five minutes without getting distracted is a useful quality for activists and the self-employed to have as well; self-discipline is not always self-stultifying. Indeed, it may be the skill needed most if one is to resist the pull of contemporary forms of control, such as advertising. The last point is one of the critical oversights of many post-modern theorists. So concerned they are about forms of policing and discipline imposed by the state that they overlook how, as Zygmunt Bauman has also pointed out, humans are increasingly integrated into today’s social order through seduction rather than discipline, advertising rather than indoctrination. Fears about potentials for a 1984 can blind one to the realities of an emerging Brave New World. Being pacified by the equivalent of soma and feelies is, in my mind, no less oppressive than living under the auspices of Big Brother and the thought police. Viewed in light of this argument, the desire to “disconnect” can be seen not the result of an irrational fear of the digital but is made in recognition of the particular seductive challenges that it poses for human decision making. Too often, scholars and layperson alike tend to view technological civilization through the lens of “technological liberalism,” conceptualizing technologies as simply tools that enhance and extend the individual person’s ability to choose their own version of the good life. Insofar as a class of technologies increasingly enable users to give into their most base and unreflective proclivities – such as enabling endless distraction into a largely unimportant sea of videos, memes and trivia, they seem to enhance neither a substantive form of choice nor the good life. In a dark room sits a man at his computer. Intensely gazing at the screen, he lets the images and videos wash over him. He is on the hunt for just the right content to satisfy him. Expressing a demeanor of ennui alternating with short-lived arousal, he hurriedly clicks through pages, links and tabs. He is tired. He knows he should just get it over with and go to bed. Yet, each new piece of information is attention-grabbing in a different way and evokes a sense of satisfaction – small pleasures, however, tinged with a yearning for still more. At last, he has had enough. Spent. Looking at the clock, he cannot help but feel a little disappointed. Three hours? Where did all the time go? Somewhat disgusted with himself, he lies in bed and eventually falls asleep. This experience is likely familiar to many Internet users. The hypothetical subject that I described above could have been browsing for anything really: cat videos, pornography, odd news stories, Facebook updates or symptoms of a disorder he may or may not actually have. Through it, I meant to illustrate a common practice that one could call “novelty bingeing,” an activity that may not be completely new to the human condition but is definitely encouraged and facilitated by Internet technologies. I am interested in what such practices mean for the good life. However, there is likely no need for alarmism. The risks of chronic, technologically-supported pursuit of novelty and neophilia are perhaps more likely to manifest in a numbing sense of malaise than some dramatic crisis.